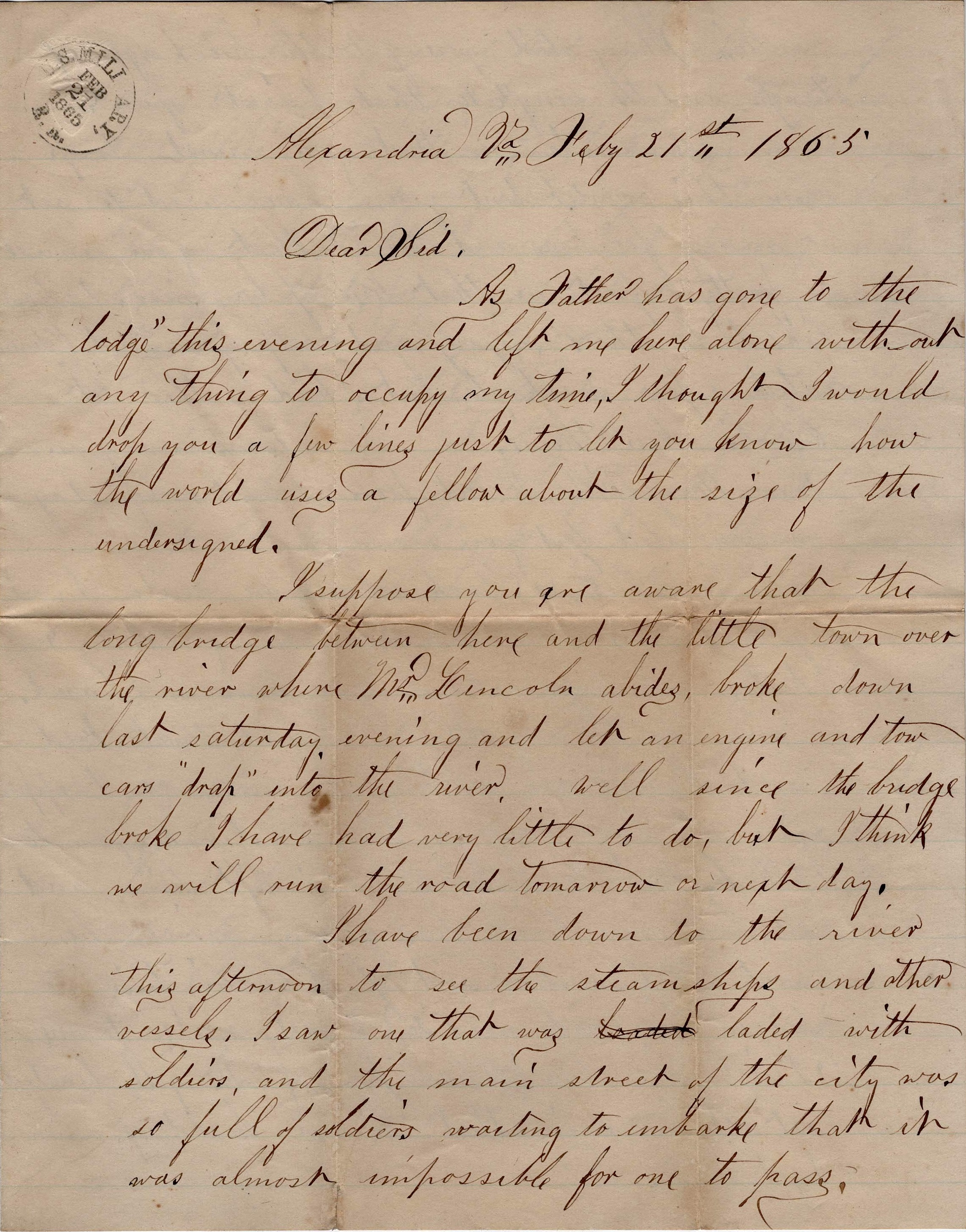

The 1864 captivity of Andrew Clark McCoy, 9th Minnesota Infantry, at Andersonville.

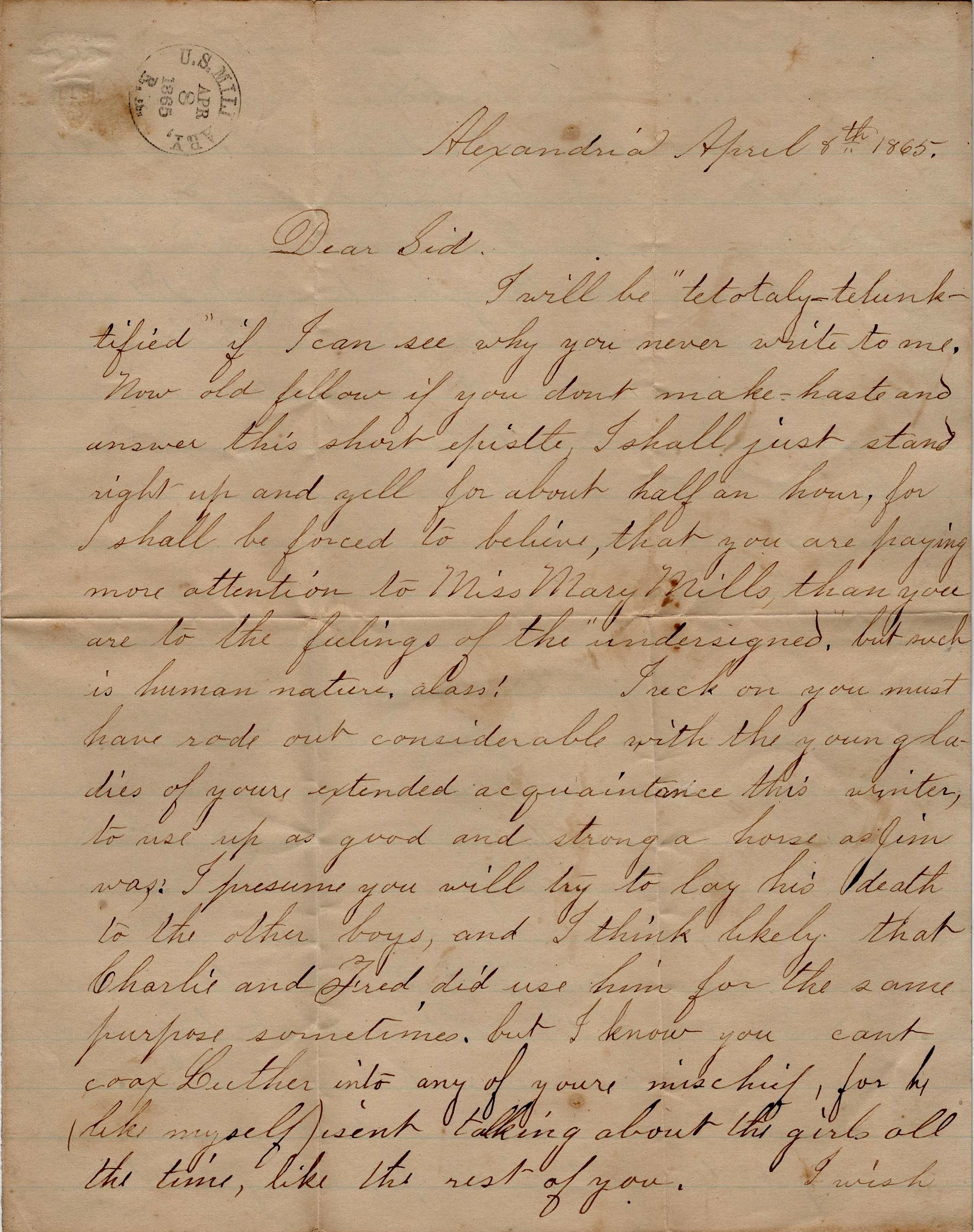

Andrew Clark McCoy (1842-1913) was born in Crete, Will County, Illinois, on December 26, 1842, and with his father’s family settled upon a farm in Salem township, Olmstead County, Minnesota in 1856. He received his education in the district school and later at Hamline University which was then located at Red Wing. While there, he enlisted in 1862 in the 9th Minnesota Infantry—a regiment that had the misfortune of earning the sobriquet, the “hard luck” regiment. This regiment was trained and used as companies on the frontier in its first year of service, scattered at various posts in Minnesota and later Missouri. In September 1863 the Ninth received a short furlough, and in October the companies departed Minnesota in groups for Missouri. Here, as part of the Department of the Missouri, the regiment spent the next seven months guarding railroads from near St. Louis westward to the Kansas state line. In May 1864 the Ninth concentrated at St. Louis. At dress parade on the evening of May 26 the entire regiment came together with all ten companies present for the first time in the Ninth’s history.

From St. Louis the Ninth Minnesota moved to Memphis, where they joined an expedition led by General Samuel Sturgis. They were tasked with protecting Union railroad supply lines from Confederate raiders while Sherman’s army campaigned toward Atlanta. On June 10 1864, Sturgis’s force clashed with Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest in the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads (Guntown), Mississippi. Sturgis’ units joined the battle piecemeal and were defeated by Forrest. Throughout the night and into the next morning Forrest pursued the federals for more than twenty miles. The Southerners captured many cannon and wagons, as well as some 1600 prisoners. 235 men from the Ninth Minnesota were sent to prison camps.”

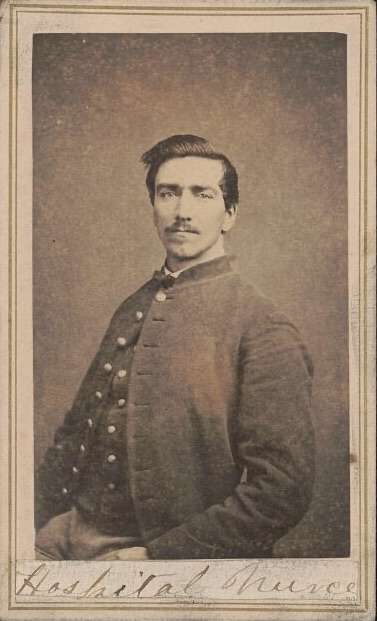

The following speech was written sometime after the war by McCoy chronicling his experience at Andersonville, the notorious Confederate prison located in Sumter, Georgia, where he was held in captivity for about six months in 1864. Following is exchange from prison, McCoy returned to his regiment and served until August 1865. Following his discharge, he returned to Olmstead county where he became a prominent farmer and leading citizen, serving as a town supervisor, as county commissioner, and as a member of the school board. He took an active part in Grand Army affairs and my hunch is that this speech may have been prepared for one such meeting. A copy of the speech was made available to the Rochester Public Library in 1908. How much earlier it was written is unknown. I have published it here because I could not find any evidence that it had ever been published. My thanks to Ryan Martin for sharing the speech.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

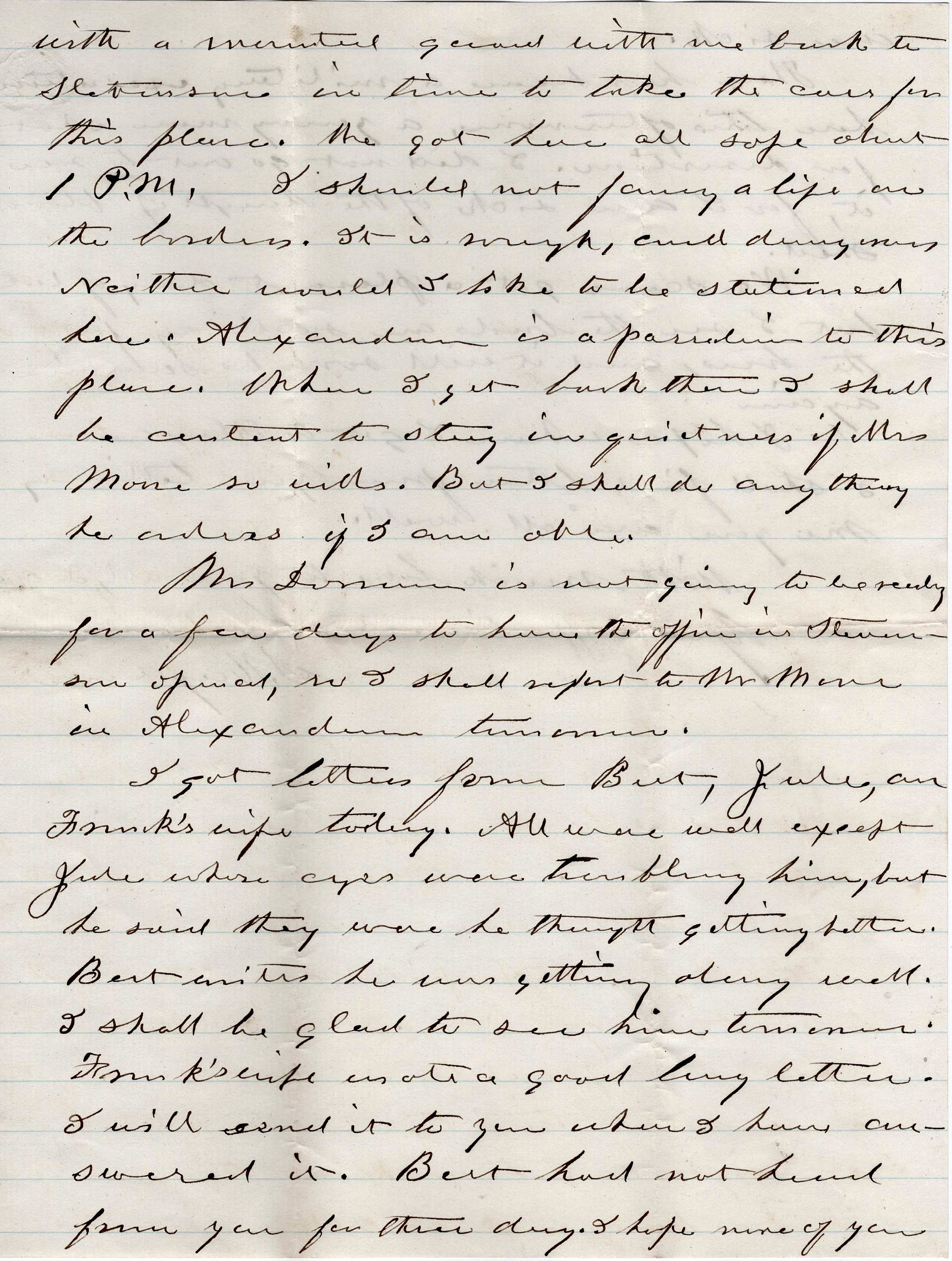

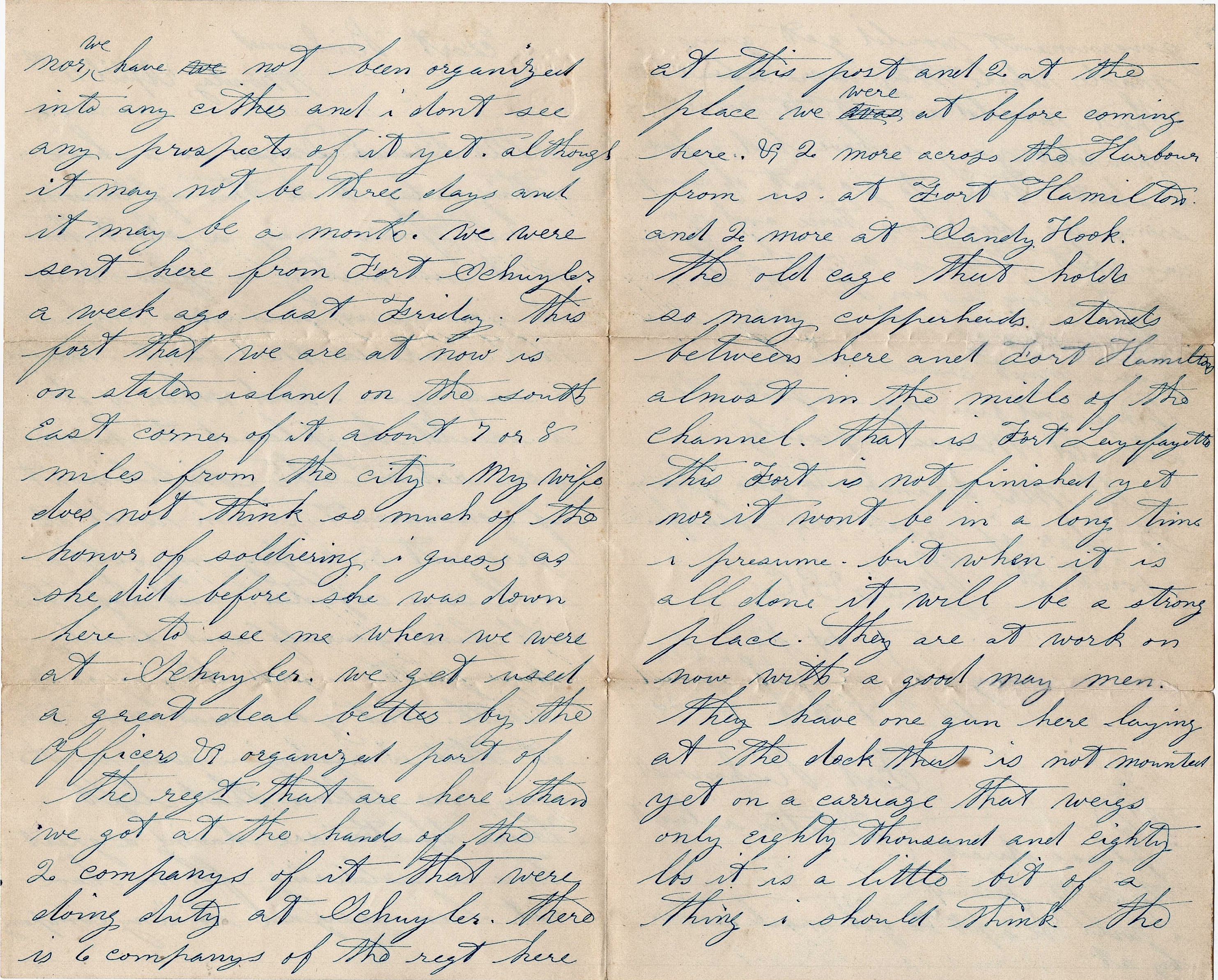

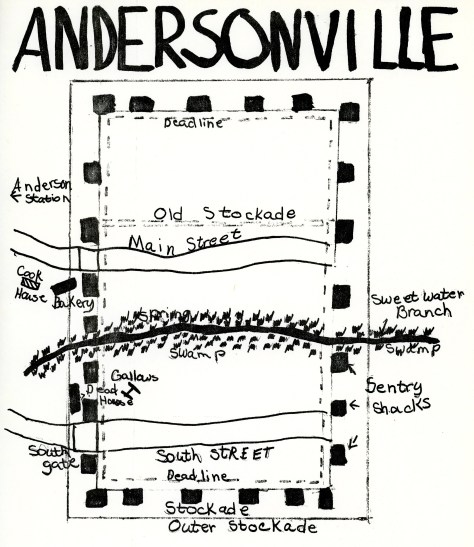

“I was a member of Company F, 9th Reg, Infantry, Minnesota. I was captured at Ripley, Mississippi on the 11th day of June 1864, the very day after the Guntown disaster. Was conveyed through Selma, Demopolis, Montgomery, and Macon to Andersonville. Andersonville is about 60 miles south of Macon and ½ mile east of Anderson, a little railroad station. The prison was simply a stockade built of logs cut 18 feet long hewn flat set in the ground 4 feet and stood 14 feet above it, the enclosure contained 13 acres, 20 feet inside of the stockade were stakes about 2 feet long driven in the ground 12 feet apart. Narrow strips of boards were nailed on tops of the stakes and this was the “dead line.” There were 33 perches around the stockade in each of which stood one guard. The prison was first occupied by federal soldiers held as prisoners of was on March 12, 1864. They were from Bell Island and Libby prisons. This prison was used about one year.” — Account written by A. C. McCoy.

A SPEECH MADE BY A. C. McCOY ABOUT PERSONAL EXPERIENCES AS A CAPTURED UNION SOLDIER HELD AS A PRISONER OF WAR BY THE ARMY OF THE CONFEDERACY

On the 19 day of June 1864 between sundown and dark, 700 of us Guntown victims stood in line in front of the South gate at Andersonville prison—and were counted off into squads of 90 men each. Three of these squads or 270 men made a detachment. The squads were numbered from one to three. The detachments were numbered in order from one side to the other of the Stockade. At the conclusion of the counting the large plank gate opened, and after passing into a sort of ante yard the prison gate proper was opened and we were ordered to go inside. While the counting was going on, Capt. Wirtz and other officers and men mounted apparently ready for any emergency.

Oh! What a sight met our eyes as we entered the prison and the terrible stench that greeted our nostrils—men half naked—complexion colored by sun and pitch pine, smoke-haggard countenances, flesh shriveled and drawn tight to the bone, eye sunken and glassy—it was difficult to believe that they belonged to the same race of beings as ourselves. The great question which presented itself to us at that time was where we could find a place to stand or sit down, to say nothing about unoccupied ground to lie down on at this end of the prison. Every inch of space seemed to be taken, but after a while we separated and found places to lie down in the narrow spaces left for the men to walk in. Our sleep was not one of rest for body or mind—and to add to our discomfiture, we were trampled on by men going back and forth from the creek and slough and the terrible tongue lashing we received for being in their way.

We got through the night without any broken bones or serious scars however, but morning found us possessed with an awful gnawing for something to eat; it being 48 hours since we had tasted food. About 8 o’clock we reported in the drive way near the South gate, according to orders received the night before, where a rebel sergeant met us and escorted us north over the creek and slough to a point northeast of the north gate where our detachment from the “dead line” and on the Second street East from it. These streets were about 3 feet wide and usually ran from the north end to the slough, there being no cross walks excepting the wide driveway at the north gate which was left for and used by the mule team and wagon that brought in our rations. This gate was only used for this purpose.

Here we remained without any shelter of any kind until the stockade was enlarged by an addition of 5 acres on the north end which when completed the north wall of the old enclosure was left standing excepting here and there two of the timbers were taken out to give access between the old enclosure and the new one. Eight of us managed to get out one of those pine timbers by considerable digging with the tools nature had given us—our fingers took it to where we had dug a hole about 16 inches deep and wide enough to permit eight of us to lie down spoon fashion, and by the use of an old hatchet we got out six stakes and material in shape and strong enough to hold up 8 inches of dirt above this hole when completed. This afforded a good shelter from the hot rays of the sun by day and dew at night—but in hard rainstorms the roof would wash off and we were obliged to pull out and stand and take it. The hole filled up with water and mud—but usually in a few hours the water soaked into the ground—the soil being a mixture of clay and sand. After the storm had passed over, we re-covered the roof. In July and August we had quite a number of hard rainstorms which was a Godsend for those confined there as it washed away many tons of filth and cleansed the enclosure generally.

Through nearly midway between the North and South gate east and west was a soft slough or quagmire. Through the center of this ran a small creek of water running from west to east. The ground sloped on either side toward this slough. On this creek above the stockade was the cook house and above that was located the camp of the guards. The wash from this camp and the refuse from the cook house entered the creek before it reached the stockade. All the water we used came from this creek. The slough was used for the offal of the prison or dumping place for all who could get there.

In order to get as good water as possible the whole camp were obliged to get it on the west side within a few feet of the “dead line.” It was here that so many of the boys were shot and killed by the guards. At this place there was always a crowd, especially so in the forenoon, of 500 persons or more, each waiting his turn at the water and in the jam and crowding some one or more would reach too far up the stream and under the “dead line.” The guards who seemed to be always alert as to the Yanks violating prison rules without using any discretion or reason whatsoever would fire from their perches on either side of the stream right into the crowd nearest the “dead line.” The offer held out furlough to any and every guard who shot a federal prisoner for crossing the “dead line.” The guards made no bones in telling us so.

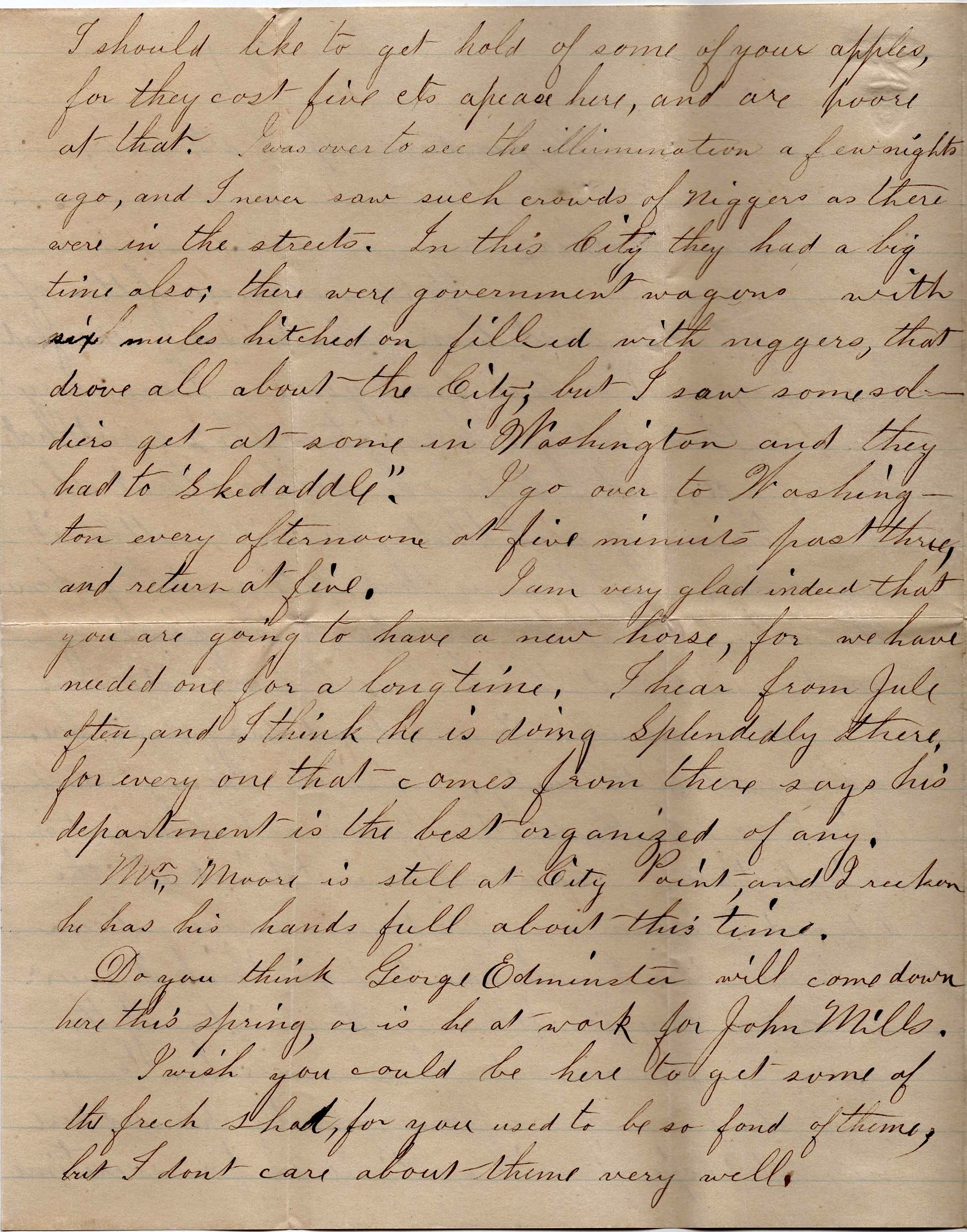

In the hands of the water brigade you could see all kinds of ingenious contrivances imaginable for carrying water, some with shoes, old boot tops, bags made from rubber blankets. I saw small buckets made from material got inside of staves with hoops, spliced the ends of which were riveted together with zinc nails taken from the heel of an old boot or shoe. Our outfit for cooking usually consisted of one or more half canteen, a tin cup and a case knife which someone of the mess brought into the enclosure or was lucky enough to find strolling from its rightful owner. We were furnished absolutely nothing inside the prison, aside rations. Lucky was the man who when captured was suffered to retain his haversack and his individual kit of field cooking utensils. Nearly all who were captured by Forrest’s men were robbed of their money, watches, pocket knives, hats and the whole private cooking outfit that was of any consequence. When our rations were issued to us uncooked, each one cooked his own, the dishes being too small for more. The outfit heretofore mentioned was the common property of the mess and in the use of which each took his turn. Arches were constructed of clay for cup and half canteen to sit on underneath of which was a fire made from a few splints of pitch pine.

Wood was a scarce article inside of the stockade and it was necessary for us to economize in its use—while not more than 80 rods from where we were we could see hundreds of cords standing in the tree. Every morning at 8 o’clock a rebel sergeant came inside, called us in line 2 deep to answer our names as he called them and as we answered he would check us off on his book—and from these checks the number of rations were issued or each check on his book represented a ration for that day. There was a sergeant for each detachment. One man of our number was appointed by the rebel sergeant to draw rations for the detachment of 270 men. Then there was a man chosen from each of the squads to draw its share of 270 rations. The detachment sergeant would divide the amount he received into three equal parts and one of those parts represented one man’s ration for a day of 24 hours. In the course of the forenoon the wagon containing our rations was driven in. For a time our ration was corn bread with a couple ounces of raw beef and at other times in lieu of corn bread would be corn meal. At other times it would be corn meal mush with no meat or salt. When mush was issued to us, it came in steaming hot and was measured out to the detachment sergeant from the wagon with a common shovel. The corn meal in whatever way it was dished up to us—whether cooked or raw—was coarsely ground and unbolted. No salt was used in the cooked food or issued to us except on two occasions and the allowance then was so small that it was of little value. Sometimes our ration would be a pint of half cooked peas or red beans which were full of black bugs. Our digestive organs could do nothing with them. On one occasion we received each a tablespoonful of vinegar and on two occasions the same quantity of sour molasses. A ration of corn bread was a piece about the size of my hand, of raw meal 1 pint, of mush 3/4 of a quart. The mush we could not keep as it would sour inside of two hours. We ate it up right away. Most of the corn bread was hardly baked through. The meat when we got any was given with one or the other named ration. The last two months no meat was issued. The raw meal we wet up with water and cooked it on the ever handy half canteen. The beef we stewed in the same dish. Our corn bread ration we tried to make last as long as possible for us to restrain our knawing stomachs. When other kinds of cooked foods were issued, we were obliged to eat it up right away to keep it from spoiling.

You understand that we were destitute of any utensils for receiving or keeping of the rations and the men who drew the food for detachments and squads had only a blanket or rubber pouch to carry the stuff from the wagon to the place of division. In my own case, I tore out the sleeve lining from my blouse to hold the rations of my mess. We had been there less than a month when our boys commenced to die of dysentery and bowel troubles caused by the quality of food received, from exposure and impure water. Nearly all were reduced to walking skeletons. The prison was a breeder of disease. The slough a bed of squirming maggots, and air impregnated with foul odors from the cesspool—and for some distance back from it the air was filled with flies bred there. The death rate was greater among those who were unfortunate enough to be located on its borders. Many died later of starvation and of that loathsome disease, scurvy, and gangrene and of other diseases bred by the scanty allowance and unwholesome nature of food received, and the want of proper sanitary regulations. The pangs of hunger were at times terrible to endure. At night would dream of home and its surroundings, of being about ready to sit up at a table spread with the most palatable layout imaginable, only to wake up and hear the groans of the sick and dying all around us, the guards cry the number of their posts and the hour of night ending with “all is well,” and then realize our dreadful situation—that we were in the hands of men who were not possessed with such a thing as pity, mercy, reason or manly consideration. Our stomachs many times would not retain the food and at other times the sight of it would sicken us. Many times in my own case while standing in the ranks for roll call, I became dizzy from weakness and could not see an object 20 rods in front of me and had to sit down to keep from falling. But this feeling wore off as the day advanced and would be able to take considerable exercise and feel quite well considering.

Our time at first was spent in studying our surroundings, playing games with devices of our own manufacture, talking, relating our boyhood experiences, &c. But the uppermost thought always to be considered was the opinion of each one as to the length of time he thought our stay would be there. This opinion was asked for many times a day—anxious to know of home, of the outside world and what our armies were doing. The want of suitable and sufficient food turned our minds in that direction, would tell of the good meals we had helped to stow away, of what they consisted and how cooked. Would even remember of the crusts of bread we had seen floating round in our folk’s swill barrel and think what a feast we would have if we could get at it. Would wonder if General Stoneman or someone else would not come down on the guards and relieve us—and a thousand and one thought of like nature suggested by one and another. Little did we think or dream that we lived under the following order which if carried out meant certain death to all of us:

Headquarters Military Prison, Andersonville, Ga.

July 27, 1864

The officers on duty and in charge of the battery of the Florida Artillery at the time will, upon receiving notice that the enemy has approached within seven miles of this post, open upon the Stockade with grapeshot, without reference to the situation beyond these lines of defense.

John H. Winder, Brigadier-General Commanding

[Original clipped from newspaper taken from the Confederacy records]

Our daily routine was about this—1st, in line for roll call—2nd, draw rations—3rd, cook and eat same—4th, if any of our friends were sick to help or carry them over to the south gate and there wait with them their turn to be taken before the doctor—5th, if any of our number had died during the last 24 hours to carry him out through the south gate and leave his body there to be picked by the burial party and while out there to pick up some wood and bring back with us—6th, would skirmish for vermin, first take the shirt and then the pants and go over each article carefully—usually twice a day—and if there were any in our mess who were unable to look over their own clothes someone would do it for him. These little demons increased in number and size most rapidly and throve the best of anything I ever saw or heard of in all of God’s creation. I know they sapped the life’s blood from many a poor fellow’s veins. As a matter of fact, all those who had been confined there any length of time were reduced in flesh and strength and had but little blood left in their body. The ground was alive with the vermin. It was no unusual thing to have the outside of our clothes covered in the morning so thick that we could scrape off these pests with a knife or rather a stick with the edges sharpened. We had no chance to wash our clothes and they were worn until they literally dropped off us, which were replaced by stripping the dead who were taken out nearly naked. Usually a shirt or a part of a blouse was left on them. The dead were laid out with hands crossed below the breast, wrists tied together as was also the feet. The name, regiment, and state to which he belonged was written on a piece of paper and fastened to the breast of the garment left on him.

The sick were often compelled to wait 3 or 4 hours in the hot sun before their turn came to see doctors. Many died there while waiting. It became useless to go to the gate for medical aid from the fact that the doctors had no medicine to give excepting the steepings of weeds and herbs said to have medicinal properties. The hospital on the outside was always full and it was generally known that to go there in nearly every case was but so many steps nearer the trench. Many times when our young Johnnie came inside to call the roll, he would report to us the death of this and that one of our detachment who had left for the hospital but the day before. During the months of July and August there was about 35,000 persons confined in the stockade and the average daily death rate for those two months was 200. The number of inmates was kept up by new arrivals from Grant’s and Sherman’s armies. From these arrivals we learned what our armies were doing. The Johnnies only let us know of federal reverses. During the long time confined there I never saw a newspaper of any kind.

When the new arrivals came inside, the boys in their eagerness to gain news would gather and stand around them in great immense crowds which the rebels in their fear, or otherwise, construed to be a gathering to plan an outbreak. So one day some of the guards came inside and stuck stakes with white stripes of cloth fastened to them through the center of the stockade north and south and orders were given that if we congregated on the west side of this line of stakes—that is, on the side next to the gates—they would open on us with shell and canister. They did one afternoon by firing two guns. One shot went clear over the stockade. The other struck between the dead line and the wall of the north end.

During the last week in September, they took the first trainload of men out. It was supposed for exchange—in fact, they told us it was. But after the second trainload was taken out, all such hopes were dispelled. Our show began to look blue and no wonder that some became discouraged and gave up and in their delirium crossed the “dead line” that the guards might put an end to their miserable existence. It looked as if our only show to escape from death was by taking the Oath of Allegiance and enter the Confederate service. This inducement was constantly held out to us. They called for men to go out on parole to make shoes and for men who were acquainted with machinery who could run and keep the same in repair, offered great inducements to such, but few expressed a desire to go and those who did were reasoned with by their fellows and most cases were persuaded to remain inside. Those who did go outside on parole did it thinking their show for escape would be better and with the intentions to do so at the first opportunity offered. A fixed determination generally prevailed that no one, let come what may, would do anything to aid or help the rebels—or in short, “Death before Dishonor.”

Some of their modes of punishments aside from cutting off rations were: They tied men up by their thumbs to limbs of trees so high that their toes would just touch the ground and kept them there in that position from 8 to 10 hours at a time, or until the victim fainted. One day out by the south gate, I saw men laying on their backs with the hot southern sun beating down on them, their feet fastened to stocks, arms stretched out full length, their wrists tied to stakes driven in the ground in such a position that it was impossible for them to shift their position in any way. One of our boys who had helped to carry a dead person out borrowed an ax of a negro to cut up some limbs of a tree to carry inside, he concealed the ax in such a way as to elude detection of the two guards at the gate and brought it inside and when the ax was missed they compelled the negro with a guard to go inside and pick out the man who had the ax, which he did, and he was taken out with the negro and they were both ordered to bare their backs. The negro’s hands were tied to a short post and a rawhide whip of 3 strands was given to the white man and he was ordered to give the negro 30 hard lashes. He remonstrated but was told he must do so, or he would received a double dose. After he had whipped the negro, they changed positions from active to receptive—vice versa. There were kept on the outside of the stockade at the southeast corner in a covered shed, a dozen bloodhounds in charge of their master. They were kept and used to capture escaped prisoners and paroled men who attempted to run away. Quite a number of tunnels were dug from the inside under the stockade well and those who escaped through them were scented by the hounds, and run down or treed in a few hours after their escape had been discovered (of course these escapes were made at night). The poor runaways were obliged to climb a tree in order to keep the hounds from tearing them to pieces before their mounted master came up to call them off.

Three weeks before I was paroled for exchange, I was removed to Savannah, Ga. I was there one week at the end of which was taken to Milan or Camp Lawton—both prisons were stockades. The enclosures were constructed of the same material and in the same way as Andersonville. At Savannah the dead lines were lit up at night by lamps but we were crowded in there to almost suffocation. Rations were better, however, both in quantity and quantity. At Milan the stockade enclosed 60 acres and there were not over 8,000 of us there. The prison was new and had not been occupied more than a week before our arrival. The treetops of timbers cut for the enclosure were mostly there so wood was plenty. We needed it badly for it was getting to be pretty cold and frosty at night. Quite a stream of water ran through the stockade and no slough. By the use of this stream and some fixing up which was done before it was occupied made it more healthy and in accordance with true sanitary rules. Was there two weeks when on one afternoon in the first week of December 1864, a rebel sergeant and surgeon came in and called for all the sick to fall in line. The boys were a little slow about it, had been fooled so many times that they thought there was some game in it, but I said to my mess, “I’m going to see what’s in it anyway.” I had no more idea I would pass or that it meant exchange than I have of owning this hall. I took a place in line and when the surgeon came to me, he looked me squarely in the eye and said gruffly, ‘What’s the trouble with you?” I answered, “Bone scurvy.” He pinched my right arm midway between the shoulder and elbow joint, turned to the sergeant and said, “Put his name down.” As fast as our names were written down, we were separated from the rest and were formed in a separate line and as soon as there was a train load of us, we were marched to a vacant corner of the stockade where we stayed that night under a special guard. The next morning we went through the gate en route to the station 3/4 of a mile away, walked along the road between the files of guards. It took me ½ day to walk that distance and I did my best!

We boarded a flat car and rode all night in an awful cold rainstorm. Arriving at Savannah in the morning, we found men with tables and blank paroles for us to sign. While waiting my turn I noticed that there were some dead bodies carried from the cars, this was no unusual occurrence in the transporting of men from the rebel prisons. After all the men had signed their paroles we were marched to the river past Fort McCallister and to our fleet of transports. Steamed alongside on the them, a gangplank was laid down between the two boats a Federal stood on one edge, a Butternut on the other of the plank, and counted us as we passed from one boat to the other. It was not long before we were treated to “Yankee food,” after which we washed and scrubbed ourselves, hair and beard trimmed, after which we donned decent clothing. In a few days we were examined and those who were thought to be able to stand the trip were put on board an ocean steamer for Annapolis, Maryland. The others were left on hospital boats we passed. And after three days passage, arrived at Annapolis and had the joyous satisfaction of planting our feet once more in “God’s country, and standing beneath “Old Glory ‘Free’.”

There were 184 of the 9th Minnesota volunteers in Andersonville. 128 died there; 56 came out alive. Of my Co. F, 19 were captured; 13 died in prison. Only 6 came out alive.