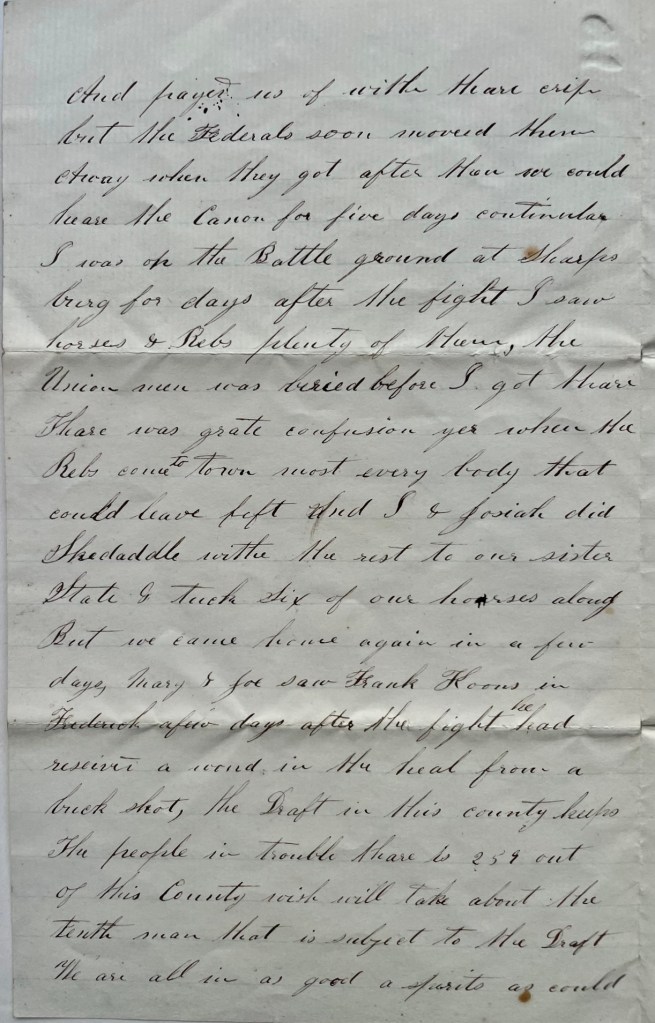

The following letter was written by Lewis Augustus Snook (1836-1928), the son of Daniel Snook (1799-1886) and Ann Margaret Hill (1799-1848). It was Lewis’ older brother Josiah Snook (b. 1827) who took over his father’s farmstead (pictured above at the homestead) but at the time this letter was written in the fall of 1862, 63 year-old Daniel still lived with several of his children in the house, including 26 year-old Lewis and 32 year-old Mary. When the 1860 US Slave Schedules were tallied, Daniel Snook owned two slaves—two mulatto females, age 20 and 24.

Lewis’s letter describes passing over the battlefield at Sharpsburg four days after the battle. He observed that most of the Union solders had been buried but there were yet Confederate soldiers still awaiting burial.

This letter is from the personal collection of Greg Herr and was made available for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.

Transcription

Utica Mills [Frederick county, Maryland]

October 26, 1862

Dear Sir,

I thought it was now time for me to write to you in answer to your letter of the 27th June but I know that I have not waited as long as you have or did. But I thought you would like to hear from your poor old pap and the rest of the family. We are all very well at present and hope you are the same.

You wrote in your last letter that you was in a bakery. I guess by this time you are perfect, but I must now tell you what is going on down here. Uncle Sam is everywhere we thought, but when the rebels come over to pay us a visit, there was not a blue coat to be seen. They [the rebels] was in Frederick about a week but they did us no damage but took about a hundred dollars worth of corn and oats and paid us off with their script. But the Federals soon moved them away when they got after them.

We could hear the cannon for five days continually. I was on the battle ground at Sharpsburg four days after the fight. I saw horses and rebs—plenty of them. The Union men was buried before I got there. There was great confusion here when the rebs came to town and I and Josiah did skedaddle with the rest to our sister state and took six of our horses along. But we came home again in a few days. Mary & Joe saw Frank Koons 1 in Frederick a few days after the fight. He had received a wound in the heel from a buck shot.

The draft in this county keeps the people in trouble. There is 259 out of this county which will take about the tenth man that is subject to the draft. We are all in as good a spirits as could be expected in war times— Darkeys and all of us. Oh, Dan Shaffer is not married yet. There is still hopes for you. Oh by the way, I just thought of one thing. Would you let me have them pants of yours made of some homemade goods that you wore some the last winter you was here. If you would sell them to me, I will pay you what is right unless you wish to keep them. Mary told me to ask you about them and if you think you will spare them, please write directly and let me know or I must buy a pair before long. But I will wait to hear from you. Let me know the least you can take for them and what kind of money—I guess green backs—and I can send it to you.

Do not neglect writing directly for Mary is wanting to hear from you bad. She often wants me to write to you but you are so slow to answer. Nothing more at this time. Our compliments to you, — Lewis A. Snook

This is a very rainy night. Write soon. Goodbye.

1 Frederick Frank Koons [Koontz] (1833-1915), a native of Frederick county, Maryland, who was a machinist in Ashland, Ohio. He enlisted as a private in June 1861 to serve in Co. G, 23rd Ohio Infantry. He was wounded at South Mountain on 14 September 1862. He later rose to 1st Sergeant of his company. He was married to Sarah Ellen Potter in August 1853.