The following excerpts from letters and diaries of soldiers and citizens, still retained in private collections, were all published on Spared & Shared in the last 15 years and shed light on the Battle of Fredericksburg and the morale of the armies before and after the battle. These accounts offer a thought-provoking perspective, exposing hidden truths and intimate experiences only found in private letters. Filled with raw emotion, these letters and diaries help us shape our understanding of the war.

There are a total of 83 different Union soldiers (in 73 different regiments) who wrote letters or kept diaries from which these extracts were drawn; 4 in the Army of the Potomac (AOP) Headquarters, 18 in the Left Grand Division, 26 in the Center Grand Division, 28 in the Right Grand Division, 5 in the Reserve Grand Division, and 2 unidentified soldiers. Unfortunately, there are only three from Confederate soldiers, two of whom were eyewitness to the battle. In addition, I’ve included here 3 excerpts from letters written by Union soldiers not at the battle, and 2 by civilians (see index).

As one delves into these personal accounts, a stark and unsettling reality unfolds. The morale of Burnside’s Army of the Potomac was anything but strong; it was a concoction of disillusionment and despair. Many enthusiastic volunteers who had rushed to enlist in 1861 now languished in fatigue and frustration, disheartened by the agonizingly slow march towards victory over the rebellion. While a fresh influx of recruits and new regiments in the fall of 1862 offered a fleeting glimmer of hope, the Lincoln Administration’s pivot to the liberation of slaves crushed the spirits of many. There was a pervasive belief that their officers were inept and cowardly, with the fighting spirit burning bright among the troops, who felt betrayed by their leaders. A growing consensus painted politicians and War Department officials as corrupt self-serving puppets, prioritizing their selfish agendas over the fight for the nation’s soul.

Entering the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Army of the Potomac faced more than just the enemy; they grappled with relentless weather torments that delayed their movements, sometimes limited their rations, and they were plagued by shoddy footwear—many were left completely barefoot. Anxious and apprehensive about being forced into a winter campaign, they resented the pressure from a demanding public, who seemed oblivious to the harsh realities they endured.

After the Battle of Fredericksburg, the morale of the Army of the Potomac reached an unprecedented low, surpassed only perhaps by the disheartening experience known as “Burnside’s Mud March” a few weeks later. A significant number of Union soldiers came to believe that continuing the fight against the Confederate army was futile, deeming it impossible to ever conquer them. Despair nearly took hold, and it may have prevailed entirely were it not for the astute leadership of President Lincoln, who publicly recognized that although the assault on Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had failed, the Union army had displayed remarkable skill and courage in their efforts, while he also acknowledged and empathized with their considerable losses.

All of the letters and journal entries presented here are organized in chronological order by their writing dates, providing a clear insight into the state and morale of Burnside’s army leading up to the battle. I have categorized them into three distinct sections: Before, During, and After the Battle; however, it is important to note that letters dated during or after the battle often include descriptions of the preceding events. One letter, in particular, stands out as the definitive account of the battle from start to finish: the account by Edgar A. Burpee of the 19th Maine Infantry. I am particularly grateful to Derrick Williams for generously sharing this remarkable piece from his personal collection. If you find yourself short on time, I strongly recommend dedicating at least a moment to read Burpee’s letter, dated 15 December 1862.

Related Reading

Burnside’s Bleak Midwinter, by Albert Conner, Jr., and Chris Mackowski, 3/21/2017. (HistoryNet)

Before Battle Letters

James Henry Clark, Co. A, 3rd Vermont, 2nd Brig., 2nd Div., VI Corps.—Left Grand Division (The Civil War Letters of James Henry Clark)

Camp near Aquia Creek, November 19, 1862 to his cousin.

“You ask me what I think about the war. Well, that is a hard question and I don’t know as I can make you understand just what I do think about it. In the first place, I will tell you what I know and then what I think about it. First, they are making a regular political thing of this war. The Democrats and the Republicans are now having a great struggle to see which shall be master instead of united and forming one grand Union Party as they should do till this war was ended. But this party spirit has become so powerful that the two parties are almost at swords points—they having become so antagonistic—and as long as it remains so just so long the war will not be prosecuted successfully. That makes out to be one fact. And now secondly, our generals, I think, are too jealous of each other. One is afraid that the other will do something and get his name up and they are so jealous that they do not cooperate nor work together as they might if it were otherwise. And then we have a great many officers that are both unworthy and inefficient and really incapacitated for the offices they hold which were, perhaps, obtained for them through their wealth or the interference of friends, or maybe by their former station in society. This is all wrong and not as it should be.”

Henry Fitch, citizen, Bergen Square, New Jersey (S&S18)

Bergen, New Jersey, probably Wednesday, November 19, 1862 to his son.

“I see by the papers that railroad is finished from Aquia Creek to Falmouth, that the pontoon bridges have arrived ready to be used for the crossing of the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg and that our gunboats are on their way up the river and nearly to Fredericksburg. From all this I infer that you will move soon from Stafford Court House and will meet the enemy in battle at Fredericksburg unless they retire beyond reach of our gunboats to a more defensible position. I see by the papers that the force of the enemy under Gen. Lee at Fredericksburg is estimated at 100,000 & will reach 125,000 before Burnside gets ready to fight them, but that Burnside says he has plenty of men to do all his work.”

Samuel Brown Beatty, Co. E, 57th Pennsylvania Infantry, 2nd Brig., 1st Division., III Corps.—Center Grand Division (S&S22)

Camp on the Rappahannock, Eleven miles from Fredericksburg, Va., November 20, 1862, to his wife.

“Sabbath morning, Nov. 23—Four miles from Fredericksburg. As I did not get my letter sent when I commenced it, I thought I would write some more and let you know something about our travels since we crossed the Potomac. We have marched about one hundred and seventy-five miles and we are not at Richmond yet. It is getting some cold and disagreeable but I have not suffered any with cold yet. I have all the clothes I can carry on the march and I hear nothing about winter quarters yet. We have eaten our last cracker this morning and we do not know when we will get any more but we have never starved yet and I think we will get bread before very long. I am very glad that you do not know how we get along here in the army but then it might be worse.

I got a letter from you last night dated the 10th. I was glad to hear that you were well. You must not get discouraged about anything much less about writing for I get the most of your letters and it does me a great deal of good to hear from you. I still hope that I will see you at some time and then I will be able to tell you all about our fatiguing marches and sufferings and privations. I suppose tomorrow we will try to cross the Rappahannock River and the Rebels are on the other side and we will have to force our way across, but we will do our best to cross.”

George Morgan, Co. F, 11th New Hampshire Infantry, 2nd Brig, 2nd Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (When I come Home)

Fredericksburg, November 21, 1862, to his father.

I have a little leisure time and I will try and write you a letter to let you know that I am alive and well but we are a having a pretty hard time of it. It has been a raining now for three or four days and it is muddy and bad traveling now. We got here the 12th. The city is held by the Rebels. We come right close to the city but they did not trouble us any. They say that Burnside has sent in a flag of truce giving them a short time to surrender the city. If they don’t surrender, I suppose that we shall have to fight a battle here before many days. I can write what they tell me but we don’t know where we are a going nor what we are a going to do one day afore hand. They tell us that we are a going from here to Richmond. They say that we have got to stay here about a week so that they can get along supplies. It is sixty miles from here to Richmond. They say that we can go there in six days but suppose that we shall have to fight some before we get there.

Last night we had to move off into a piece of woods. It got so muddy that we could not stay where we were. We built up a good big fire and so we laid very comfortable all night. There is a large army here now and there is a good many of them sick. There has eight or ten died out of our regiment. There has not any died out of our company but there will be alot of them die before spring if we stay out here…It is a pretty hard case to get much to eat but meat and hard bread. We get some fresh beef and salt pork and some bacon. We ain’t allowed to steal anything on the road. The Rebels property is all guarded. The army ain’t allowed to destroy anything as they pass along.”

Horace Augustus Derry, Co. D, 20th Massachusetts, 3rd Brig., 2nd Div., II Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S10)

November 22nd 1862, Camp near Falmouth, Va., written to his mother

“…We are paddling around in the mud now up to our knees. It has been raining for 3 or 4 days but it is a little pleasanter today and we are drying our things. Yesterday in the afternoon, I was ordered to go and get 24 men and go on guard over to Gen. [Darius] Couch’s Headquarters and over we went through the mud. We stopped there until dark and then there was 24 more came and I went and found out there was some mistake about it and they told me I might take my men and go back to camp and back we went through the mud again and that is about the way things are done all of the time. I shall be glad when we get some of our old officers back that knows something. Captain [Ferdinand] Dreher has got command of the regiment now. He is a Dutchman. You know we have been on the march the most of the time since I came back. One day they marched us 20 miles and all we have on the march to eat is raw pork and hard bread. The boys find a great deal of fault and say they do not have enough of that. We are close to Falmouth and on the other side of the [Rappahannock] River we can see the rebels on picket and we expect to cross in a few days. The pickets are near enough to talk to each other. We do not get many letters now for the mail does not go nor come regular now and I do not think it will until we get into winter quarters and I don’t know when that will be. I do not see much signs of it now and for my part, I do not want to go into winter quarters. I want to fight it out and come home…”

William Washburn, Jr., Co. A, 1st Massachusetts Infantry, 1st Brig., 2nd Division., III Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S20)

Camp Mass. 35th Regt. near Falmouth, Va., November 22d [1862] to his friend.

“Fredericksburg, which is in plain view from the place I write from, is a much smaller city than I expected to find it. It looks very prettily from a distance, situated as it is in a hollow on the banks of a fine river, with very high hills in nearly every side. If its streets present no better appearance upon close inspection than did those of Falmouth, I can’t speak much in its favor as a cleanly city. However, I may not have an opportunity to form an opinion in that respect, for there’s every prospect now of being obliged to shell the place before the rebels will surrender it. In that event, it will probably be entirely destroyed, or so disfigured as to make it impossible to gain an idea of its previous appearance. We have now been here for three days, and during that time the cars have been running constantly to and from Fredericksburg, either bringing reinforcements to, or carrying supplies from there.

Today, the sun has appeared for the first time since arriving in Falmouth. The roads are in a terrible condition from the heavy rains which have just ceased. Wagon trains, ambulances, and every conceivable kind of vehicle traveling the turnpikes, meet with the same fate, viz: “Stuck fast in the mud.” A few days of sunshine will dry up the roads in a measure, and allow the forward movement to go on. Another great drawback to the advance is the want of shoes. Perhaps you will be loathe to believe it, but it is a fact nevertheless, that a great many of our soldiers—even in this new regiment, are entirely destitute of shoes or boots. Some are actually bare-footed, and out of my company alone, numbering now but sixteen, twelve are unable to march any great distance because of the worn out condition of their shoes. Requisition after requisition has been sent in to headquarters, and always with the same result. “You will get them as soon as they come,” is the invariable answer, and in the meanwhile, the soldier is obliged to go around in his bare feet, or wear shoes so full of holes as to render his going any distance without wetting his feet an impossibility. Whose fault is it? If government is unable to better provide for its soldiers than this at this season of the year, it had much better send the men home for they cannot stand it a great while longer. I’ve sent in a new requisition for shoes for my men this morning, and the only comfort I got was that they were probably on their way from Washington.”

Dwight Jairus Brewer, Co. F, 20th Michigan Infantry, 1st Brig., 1st Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S22)

Opposite Fredericksburg, November 24th [1862] to his sister.

“We are now 30 or 40 miles from Richmond and about 6 miles from Aquia Landing. Our forces are in possession of that place and the railroad from there here so that it is easy to get provisions to us. We shall probably cross the river—or attempt to cross—soon as our men are placing a pontoon bridge across. The rebels can be seen on the other side and our men talk with them across the river.”

George W. Fraser, Co. E, 122nd Pennsylvania Infantry, 1st Brig., 3rd Div., III Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S17)

Camp near Rappahannock River, November 25, 1862, to his brother.

“We are encamped about 1½ miles from the river opposite Fredericksburg. The town is said to be still in the possession of the rebels but will soon be shelled if not evacuated. We occupy the left of the Center Division of the Army of Virginia, being the Third Army Corps. The whole army commanded by Gen. Burnside moves together whenever any part of it moves. We are all in very good health and some of us are growing stouter although rations are very scarce on account of the large number of troops gathered here and the inconvenience of the transportation.”

Wilber H. Merrill, Co. H, 44th New York Infantry, 3rd Brig., 1st Div., V Corp—Center Grand Division (S&S23)

Camp near Fredericksburg, VA., November 25, 1862, to his parents.

Well here we are down near Fredericksburg where we were soon after we left Harrison’s Landing. The rebels occupy the town in force. The report is that Burnside has given them fourteen hours to remove the women and children. They say that they are busy at it now. I don’t believe that they will stand and fight here but they may. I don’t pretend to know. Only sunrise will tell.”

William Henry Jordan, Co. K, 7th Rhode Island, 1st Brig., 2nd Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (William Henry Jordan)

Camp near Fredericksburg, Va., November 26, 1862, to his parents.

“We have been laying here for several days for some reason unknown to us. How long we shall stay here, I do not know. I suppose you have read all about it in the papers before this time and I do not know what to write. There is all kinds of stories agoing in camp. The story is now that we have orders not to open upon the town for there is not going to be any more fighting till after Congress sits. It looks very reasonable by our laying still here so long for our batteries are all planted, ready at a moment’s warning, and the City would be ruined in a very few moments.

I think God is having a hand in it and it will be all right. I fear that you borrow too much trouble about us. Oh, do not feel too uneasy about me — only remember me at the throne of grace. I feel confident that God will carry me through if I trust in Him which I am endeavoring to do.”

George Morgan, Co. F, 11th New Hampshire Infantry, 2nd Brig., 2nd Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (When I come Home)

Falmouth Heights, Virginia, November 27, 1862, to Austin

“I take my pen to write you a few lines to let you know that I am well. I say that I am well enough but I have got the yellow jaundice and half of the regiment has got them and I want mother to send me out a little wormwood in a letter for that is the best of anything that I can take.

It is Thanksgiving in New Hampshire but it is about the same with us as any other day. We don’t have anything to do today. The officers has all gone off — I suppose to a good supper. The weather here is a getting cold and rainy. Last Tuesday, three of our company went off on picket duty. We went over to the Rappahannock River. We was posted right along on the side of the river opposite the city of Fredericksburg. The river ain’t more than 10 or 15 rods [~70 yards] wide. The Rebel pickets were right along on the other side of the river but they did not trouble us nor we them. We could talk with them across the river but I did not say a word to them.

That [Fredericksburg] is a nice looking place — what we could see. The buildings come right down to the river. There was two bridges destroyed here by our folks — one railroad bridge and one other, but they are a going to put a pontoon bridge across and they say that we have got to go across into the city but I don’t know when. Then we shall have to fight some. They have been telling that they were a going to bombard the city the next day ever since we have been here. The thing of it is, they don’t dare to fight. They are afraid of the Rebels. I expect this war will be settled up before long. They are all a getting tired of it and they don’t want to fight any longer.

We have got to go into winter quarters before long for it is getting cold now. The ground freezes here every night and we shall all freeze to death if we don’t go down further south before long. But I guess I can stand it as long as the rest can. The biggest part of them has got their boots all wore out — some of them are just about barefooted. My old shoes are good yet but I should [have] a pair of boots now. I have not had my feet wet since I have been out here by the shoes leaking…The teams out here are as bad off as the soldiers. The horses and mules are as poor as crows. They are a dying off every day. They will have to have a new set before long.”

Martin VanBuren Culver, Co. A, 16th Connecticut Infantry, 2nd Brig., 3rd Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S4)

Camp near Fredericksburg, Va. November 27, 1862, to his sister

….I don’t know how long we shall lay here but there don’t seem to be any move at present. But still we may move tomorrow….It is cold here. We have to wear our overcoats most all the time. We have got a new colonel from the 8th [Connecticut]. His name is Upham. He is only acting in place of Beach for he has gone home sick. I don’t think that he will get back this winter if the war lasts. We have all kinds of rumors here everyday but I don’t mind anything about them. They [say] that we shall be home by Christmas but I don’t want you to say so from me for I don’t think that. It is too good to be true. But I wish that it might be so for I have got sick of it and all the rest of the soldiers and I think that they have got sick both North and South. I think that it will be settled this winter but it may not be so…..This is a lonesome day to me for I am thinking of home today all the time. I am out of money, out of tobacco, and out of everything else. If you will send me some money and a pair of gloves, I can get along till we get paid off—if I live long enough….

Charles Clarence Miller, Co. D, 140th New York Infantry, 3rd Brig., 2nd Div., V Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S21)

November 27th 1862, Camp near Fredericksburg, to his parents.

“Since I wrote to you we have moved on again towards Aquia Creek and Fredericksburg. There is about 40 thousand rebels at Fredericksburg. We are in camp only two and one half miles from there but we have a very large force here but it will be a very hard place to take, I think, on the account of crossing the river as there is no bridge over the river. But we could easy burn the city by throwing shells into it as we are elevated so much higher than it. They have given them so long a time to surrender and if they do not, we will burn it to ashes.”

Joseph Donnell Eaton, Co. I, 1st Maine Cavalry, Escort 1st Corps Headquarters—Left Grand Division (S&S9)

Frederick City [Maryland], November 27, 1862 to his father

“…The Army of the Potomac has come to a halt at the Rappahannock but I trust it will soon be on the move again. Burnside will cross in spite of all opposition, though no doubt he will have to burn the city of Fredericksburg. He holds the very position that McDowell held last May when we were there and I tell you, when he opens his siege guns on that city, it will be a hot place. I hope this winter campaign will close this war. The weather is fine now and if it continues so for a few weeks, no doubt there will be considerable fighting. I would like to see it all, but in this war — especially this winter campaign — it is a duty of each soldier to himself to look out for himself. I am not afraid of the fighting for I can go into a fight as easy as to a day’s work in the field, but the exposure that cavalry is subject to will kill ten to the bullet’s one. And as long as I have the privilege of good quarters and a chance to take care of myself, I shall do so…”

Will Dunn, Co. F., 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry, 2nd Brig., 1st Div., V Corps—Center Grand Division (The Civil War Letters of Will Dunn)

Camp near Falmouth, November 29, 1862, to his parents.

“There is some very strange rumors in camp now about peace being declared. It is rumored that the rebel generals A. P. Hill and Robert E. Lee of the Confederate States of America and Ambrose Burnsides—now commander of the Army of the Potomac—has come to Washington to have an interview with Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, and I hope they will compromise and in our favor for I think the rebels is at our mercy. We have army enough for to go right through them.”

John Hancock Boyd Jenkins, 40th New York Infantry, 3rd Brig., 2nd Div., V Corps—Center Grand Division (Teach my Hands to War)

Near Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 3, 1862, to Mary.

“I only received your long and welcome letter today at noon. The delay was caused partly by our being on the march from Warrenton to Fredericksburg with our communication lines cut off, and partly by the “red tape” regulations in regard to mail carriers. Letters have now to go first to Corps Headquarters. They they are sorted & sent to the Division Headquarters. Then sorted again & sent to Brigade Headquarters where they are sorted again & sent to the regiments. This delays letters a long while, though I think it will be better when the new plan gets fairly to work.

We are at present tolerably comfortable and several cords of clothing, blankets, &c arrived yesterday, which was not at all disagreeable. The boys got up a torchlight procession last night in honor of it and all night & today the camp has been perfumed with old trousers, shoes, and such articles burnt to get rid of them…

The way the wood will disappear wherever we camp this winter would astonish you. I suppose we have burnt 200,000 cords where we are encamped now. This, of course, I mean for the whole army.

I am sorry to have disappointed you by not coming, as we both expected, but you must lay it to the account of Horace Greeley and the “On to Richmond” crowd. Only for their forcing on the army when half prepared, I would have seen you & done what I could to change the direction of my letters…

I don’t know about letting you off so long without changing your name, but I can’t lose sight of the fact that I am no better to be brought home safe than were any of our gallant dead in this awful war. I humbly trust that whether He brings me through safe or not, He will give me strength to serve Him with a whole heart. Don’t think I’m canting, Mary. Twenty pound shells bring eternity very close, and I’m not of the stuff that can look lightly on “falling into the hands of the living God.” I know, Mary, that many irreligious men have done well in battle, but what right has a creature owing everything to his Maker to offend Him when so utterly dependent on His mercy? Still, let us hope that we may yet live together and serve Him as He would.

Aunt Caroline’s wonder why they fight is natural enough, but the President’s Message answers all of her questions. Separation would be continual war. We must conquer or be slaves to the leaders of the South. Better short misery than long. Better a general war for a few years than a border war always existing.”

Anthony Gardner Graves, Co. F, 44th New York Infantry, 3rd Brig., 1st Div., V Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S22)

Camp of the 44th Regiment N. Y. S. Vols., Near Falmouth, Va., December 3rd 1862 to his friend.

“The weather is very cool now-a-days—especially in the night, and one army blanket is hardly sufficient to keep us warm. It is blowing a perfect gale here today and I assure you, it is anything but comfortable out of doors. We are laying within three miles of Falmouth. Our camp is in the centre of a large pine wood. The trees are all cut down and stumps dug out and cleared way for our camp. Most of the men have logged their poncho tents up as though they was going to stay here all winter. We (the sergeants) have got a large bell [Sibley] tent which we got when we was at Headquarters doing Provost duty. It is large and if we should go into winter quarters, we will log it up and make comfortable winter quarters for us.

We have been out at this place two weeks and the reason for our delay here is on account of the army being entirely out of commissary stores. Another thing, the whole Rebel army is on the opposite side of the river and it would be impossible for this army to cross the Rappahannock here without a great sacrifice of lives, and the different armies advancing on the rebel Capitol by the way of the Peninsula, Petersburg, and on the south side, which will compel the rebel army to fall back from the Rappahannock on Richmond. Then we will advance and not until. The Rebels are in a bad state and they know it. They are half clothed and half fed, with their supplies cut off from the army for one week would compel them to lay down their arms. They are now calling on every available man to come to the rescue for they see that they are in a tight place. Our forces are advancing on them from all directions and they will soon creep into their hole at Richmond. There is one thing certain, if Richmond is not taken this winter, I don’t think it ever will be for the two year and nine months men’s time will expire in the spring which will take off half of our army so something must be done this winter.”

Charles Robert Avery, Co. K, 36th Massachusetts Infantry, 2nd Brig., 3rd Div., VI Corps—Left Grand Division (S&S12)

Opposite Fredericksburg, Va., December 5th 1862 to his father.

“We have been camped here for more than a fortnight & done nothing but cook, eat, drill, & sleep. Fredericksburg has not been shelled yet. When will it be? If the Rebs contest the ground, it will be sharp work for the Army of the Potomac to get over to them so as to have any sight at all as they are up on a hill & have their own chosen position. But then if Burnside undertakes to make an advance, I think that it will be a perfect success.

You get more news in one day than I do in one week. How does the President’s message take in Springfield? I think that goes ahead of the [Emancipation] Proclamation in one sense. It is a trying thing that will work on both sides alike. If it does not, I shall be much mistaken. If that is what Burnside is waiting for before he advances, we most likely shall not see Richmond this winter which I was in hopes to do. I hear by the Baltimore Clipper that the Reb’s military authorities will contest every step of ground even if the civil [authorities] should surrender to us the City of Fredericksburg…We have heavy frosts out here but they do not affect me & we have warm days to match. It has rained for 2 hours now so we have a prospect of more mud seeing that we did not have any when we first camped here. If we can stand this climate, what can’t we do when we get home. I expect to be at home next summer though I may slip up on my calculations…”

Will Dunn, Co. F., 62nd Pennsylvania Infantry, 2nd Brig., 1st Div., V Corps—Center Grand Division (The Civil War Letters of Will Dunn)

Camp near Falmouth, Va., December 6, 1862, to his parents.

“We are having very disagreeable weather. It commenced raining here yesterday morning and it turned into snow in the afternoon and it snowed all night until the morning. It was a hard looking for a person to live in those little shelter tents. Last winter there was thirteen of us in one tent and fine boys they were, but poor fellows—they are all either dead or discharged. There is only three of us left and we still tent to together. Us three boys has a log house built and a fire in it. We live very comfortable. I wish we would stay here all winter but that will not be for there is all appearances of a move now. It’s my wish and always has been to push on and I hope it will be settled some way this winter. I would like very much for to be ready to go home early next spring. I think when the western army makes a strike and our fleets begin to work, I think this will make Johnny Reb jump out of some of the Cotton States.”

George W. Shoemaker, Co. G, 126th Pennsylvania Infantry, 1st Brig., 3rd Div., V Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S13)

Camp near Fredericksburg, Virginia, December 7, 1862 to his sister.

“…you said in your other letter that you wanted to know how my clothes and boots is. We have got plenty of clothes for we can get clothes any time now. And my boots is very near as good as when I got them. And the whole regiment refused coats like you spoke about the drafted men having for we had more clothes than we could carry. I have got two blouses to wear now and if they would give us as much to eat as wear, we could get along. But we have plenty now for there is plenty of sutlers coming since we have got paid off. But they sell everything for four prices.”

Peter V. Blakeman, Co. A, 122nd New York Infantry, 1st Brig., 3rd Div., VI Corps—Left Grand Division (S&S4)

Virginia, Sunday [December] 7th 1862

…We started Thursday [December 4, 1862] on the march and had a hard one that day and the next day we started very early and about eight o’clock it began to rain and rained until 3 and then it began to snow and grow cold and at dark it was freezing cold and the ground was was two inches of snow on it and snowing like the devil. We had to scrape the snow off a spot to lay down on and was as wet as could be. There was no wood to be got but green pine and it was most dark when we got to our stopping place and we had a hard time of it. I faired rather worse than the company for they got there by 2 o’clock and had time to get up their tents and make a fire but we had nothing to eat — any of us. I are with the train as guard. I have nothing to do with the camp.¹ — Peter V. Blakeman

Herschel Wright Pierce, Co. A, 76th New York Infantry, 2nd Brig., 1st Div., I Corps—Left Grand Division (S&S21)

Camp of the 76th New York Vols, Aquia Creek, [Virginia], December 8th 1862, to his brother.

“I have nothing new to write except that it is intensely cold here with about 2 inches snow on the ground and as we have no stoves, it is extremely uncomfortable in the tents. We build a fire in front of our tents and enjoy it afterwards as well as we can. My fingers are now almost stiff with the cold and I have to write on my knee which accounts in a great measure for these uncouth characters and cold as it is, I must write today as we march again tomorrow. All manor of rumors are afloat and Heavy Rifled Siege Pieces are passing this point for the front at or near Fredericksburg. I suppose we shall be thrown to the front in Doubleday’s Division as it is well known that this brigade is a Fighting Brigade. Whether we shall fight at, or along the Rappahannock depends on the Rebs themselves. If they stand, there must be a fight. If they retreat, we shall follow them up.”

Cornelius Van Houten, 1st New Jersey Light Artillery, Battery B, 2nd Div., III Corps—Center Grand Division (Cornelius Van Houten)

Camp near Fredericksburg, Va., December 8th 1862, to his father.

“I had not been on duty two days before we had orders to march. Well we have been marching ever since until we encamped here and now we are under strict marching orders. We marched out to Warrenton. We stayed there a few days, then we marched back to Fairfax. Then we had travelled 80 miles. Then to Fredericksburg is a long distance. I don’t exactly know how far it is. Through all this march, it rained constantly. You can judge how the roads were with a whole division traveling over it. We marched for ten days steady. You can think how pleasant it was after we marched all day to encamp with no tents—nothing but the coverings of our guns to cover us—hungry, wet and cold, tired. I tell you, Father, I thought something about my snug little room above the warm dining room.

Father you must not blame me for getting a little homesick and wishing the war was over so I could come home. Father, if I could come home safe, I would be contented to live on the poorest fare and in a barn or cellar for we have no tents yet. It has been snowing and it is very, very cold. It seems to me I never was so cold as now. But I must not fill your ears with my troubles. You have enough to think of taking care of the family. Don’t think of me for I guess I shall live through it and if God spares me to come home again, I will be an Old Soldier or Patriot—but my patriotism is most worn out.

Father, you must not expect to see me this winter for we are not going in winter quarters at all. We expect to encamp out all the rest of our time unless Richmond is taken before spring, which event I am afraid will not happen.”

Hannibal Augustus Johnson, Co. B, 3rd Maine Infantry, 2nd Brig., 1st Div., III Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S22)

Camp near Falmouth, Virginia, December 8th, 1862, to his friend.

“The weather for the past week has been very cold—full as cold as we found it anytime last winter—and on the 4th of the month, snow fell about two inches deep and at this moment it is none the less, the sun not being warm enough since its fall to melt it a bit. If we lived like a civilized being, we should think nothing of the cold, but to have nothing to cover you from the snow, rain, wind and cold with the exception of a thin piece of cotton duck four feet square [which] is rough enough for an Indian who is used to such treatment but it comes hard for us. And withal this, the North is clamorous for an advance. Now take it home to yourself, how could you live to be very thinly clothed and as poorly fed (for I have just made a dinner off of the worst of wormy hard bread—worms just like those you find in a chestnut) to lay out on the frozen ground and with snow on that that with nothing over your head but the cold sky for when we are on the move, we seldom ever put up our shelters at night when we know we are to start again at early dawn with only one of them government blankets over you. Do you think you could stand it long? If you think you can, just make your bed tonight out in the yard with only one blanket over you and in the morning I think if you had life enough left to speak, you would say that it is impossible for a winter campaign in as cold a climate as we are in now.

This morning I came very near freezing one of my hands in going to the spring after water for my humble breakfast (for we have no protection for our hands) and it was a long time after I got back to my tent before I got the frost out of it. We have been on the ground that we are at present eight days and the men have built themselves log basements and shelters for a roof but this had to be done all between drill hours for they drill us just as if we were raw recruits. But the general commanding, seeing how the men were suffering from exposure, this morning opened his hard heart enough to countermand the order for drill today so that the men might make themselves comfortable and the brigade campground looks like a mammoth ship yard for most every man is at work on pine, black walnut, and red oak logs, and by night there will be a vast village of log houses and in these houses with a fire all night, it is all you can do to keep warm. If I had not received a box from home with underclothes, vest, boots, &c., I do think I should of froze to death for government is very dilatory in getting clothes for the men for men with bare feet is a very frequent sight. Also men without a single shirt to cover themselves with, for many are the cases in the regiment like this.

Yesterday there was a great rejoicing in camp for the men had six potatoes apiece given them by our able Commissary and we had been out so long that their appearance was like the sun after a long storm, and says we to ourselves, goodbye wormy bread for one meal at least. Are not these pleasant auspices for a winter’s campaign? Is not the future encouraging to us? Should you not think our courage will be good? Now you may think I am in bad humor, getting discouraged, discontented, heartsick, and all this, and that under such circumstances apt to exaggerate somewhat, but such is not the case. I am in as [good] spirits as ever I wish to be, but the other day I see something in one of the New England papers that got my dander up and I have only partially got over it now. It was this. There was some three-cent correspondent that chanced to be at our Division Headquarters on Thanksgiving Day and he went on to tell what they had for their dinner such as turkeys, chickens, puddings, wine sauce, and all this and that, and wound up by saying that by being in the field, we continue to live in style and how fortunate the Division was in having such as able Commissary and Quartermaster and went on to give them a puff. But if the fool had come into our regiment and seen the dinner the men that doing all that is done, suffering all that can be thought of, I think he would sing another tune for all in the name of heaven we had on Thanksgiving Day was wormy hard bread and coffee without a particle of sugar to make it palatable. And after all this, this ignoramus went on to say how well we were provided for and this same jackass went on to say that the men were all clothed and in the best of spirits, eager for an advance—the sooner the better. Now this is one of the damndest lies ever told. The men are in rags and they do not want to advance—no more than a cat wants two tails.

Now this is not an act of the men being afraid to meet the enemy for fighting is the very last thing thought of by them. The enemy that they do fear though is the cold weather which will kill more than the bullet ever thought of doing. So when you hear anyone say that the men want to advance during the cold weather, you may say to yourself that he has only visited the comfortable quarters of the general, not the uncomfortable ones of the privates. On Thanksgiving Day I could not help thinking of the two such days I passed in your family—the first one when I was with Kitty’s family, and then we passed the day at your Father’s hospitable home. The second [time was] at your home and I could not contrast those two days with the one just past and gone and note the difference. But I hope and pray that my last day of this kind is passed—that is, as a soldier—for I have passed two of them. On the first one we had pea soup. The second I have already numerated. My Father was going to send me a box of articles such as we have on such a day at home, but I, fearing I should not receive it, wrote him accordingly and I am much obliged for your good intentions. I will take the will for the deed.

I am afraid as you say that the 8th Massachusetts have seen their pleasantest times as soldiers for men now in the field are put in to fight, not to be a mere show, although some of them go in fortifications to drill at Heavy Artillery and do not have the many changes a soldier in the field is subjected to. But this class gets as much praise as if they had done all the fighting that has been done but we being in Kearney’s old Division and having got a good name (for our Division is called the “Fighting Division” by all that know us), we have got to keep in the field to keep our name where they now are. And the other day, after being reviewed by General Hooker, he told us that the first troops that entered Richmond would be Kearney’s & Hooker’s old divisions.

I am glad to hear of one person being tenderhearted, meaning yourself, and no doubt such scenes as those you passed through at the departure of the 8th [Massachusetts] aroused such a kindred feeling, and I myself considered that as one of my redeeming traits before enlisting. But being associated with nothing but men for the last 19 months, and those men seeking the blood of their fellow man, I say I have lost some of the more sensitive feelings I at one time possessed. But at the same time, I can say that in all the temptations that has been around me, that today my morals are better than they were the day I left my own native state which I know many cannot say.”

Charley Howe, 36th Massachusetts Infantry, 3rd Brig., 1st Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (Letters of Charley Howe)

Near Fredericksburg, Va., December 9th 1862, to his parents.

“Since I last wrote, the company has been on picket on the Rappahannock. We went down Thursday afternoon and everything betokened fair weather. The old City of Fredericksburg was in plain sight and the clocks could be heard to strike very plainly. The evening was beautiful—not a cloud to be seen, and the moon and stars shining in all their splendor. Dogs seem to be numerous in Fredericksburg for their barking and fighting could be heard all night long. Occasionally a loud laugh, cheer or rather yell from the opposite side of the river convinced us that the rebels were not far distant. At length all was quiet. Everyone seemed to have gone to rest but the pickets who stood carefully watching the river and rebel guards lest the skunks should cut up some of their midnight gun games and take us prisoners in the face of our army.

About two o’clock A. M., clouds made their appearance and in half an hour a cold rain began to fall which turned to snow sometime in the forenoon. About five o’clock P. M. we started for camp and when we reached it, we were a gay looking set—ice and snow clinging to our clothes and equipments. Our tents, which we fortunately had left standing afforded us but little shelter but not until we had built some roaring fires could we feel comfortable. Soon we were told that a mail had arrived and to my great satisfaction I received father’s letters of the 23rd and December 1st. This with a good supper counterbalanced my uncomfortable feeling and (to use a favorite term), I was all hunk…

What do you think of the [President’s] message [to Congress]? My opinions is that if the South don’t accept of it, they will accept of nothing and we will stay our three years out. But they will come to terms—mark my word. That message came from a long head. I think more of Mr. Lincoln than I ever did before and he can be pardoned for his past slowness. He calculated to suit in a measure all parties. Of course all will have to knuckle a little, but for all that, I think all will be satisfied unless it is the damned abolitionists. But it is not for me to comment on it. All I hope is that the loafers up North will shut up their blab about the South’s repenting their folly and all such nonsense as that.”

George W. Fraser, Co. E, 122nd Pennsylvania Infantry, 1st Brig., 3rd Div., III Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S17)

Camp near Falmouth, Va., December 9, 1862, to his brother.

“Our present camp is within 1½ miles of the town of Falmouth which is situated on the Rappahannock river opposite Fredericksburg. The rebels are said to occupy that city with a strong force. Our pickets are on this side of the river and the rebels right opposite. It is rumored in camp that three of their pickets were frozen to death the other night. This is indeed quite true as they are very scant in clothing—some having no shoes to their feet and not more to cover their body than a shirt and a pair of torn pants. They are indeed a pitiful set of human beings. I and no one else can understand why so many troops should be lying idle here at this point. Some think that the army is waiting for supplies; others think that Burnside is afraid to make the attack and waiting for Congress to try to offer a compromise to the rebels. But I am very much inclined to think that we are holding them at bay here at Fredericksburg while the greater part of the army is approaching Richmond by way of the Peninsula and James river. This is only my opinion and I hope is very near correct. We are not yet in winter quarters but it is generally supposed that we will stay here for some time. Some of the boys have built their winter huts. I have none yet but will commence building tomorrow. There is snow on the ground but the weather is generally very pleasant for this season of the year….Our regiment is not as healthy as it might be. The general complaint is rheumatic fever and jaundice.”

James Sanks Brisbin, 6th U. S. Cavalry, 2nd Brig., Cavalry Div. —Right Grand Division (S&S23)

Camp 6th US Cavalry, Belle Plain, Virginia, December 9th, 1862 to his wife.

“The river is now frozen over but not hard enough to bear. If the river gets solid, I think we will either go over or the Rebs will come over. All the people of Falmouth and Fredericksburg are camped out. It must be pretty cold on the women & children.

I think the great battle of the war is at hand. All other battles will be as nothing when compared with it. They say we have four hundred thousand men here. I think not so many as that but we certainly have three hundred thousand and that is a good many men. The Rebels must have two hundred and fifty thousand so we will be able to get up quite a respectable fight. Half a million of men fighting will raise considerable smoke and dust and make quite a noise.

I suppose you would not care if there was a fight & they did keep me under arrest and keep me out of it, but I would not miss the next battle for anything. I would rather lose a leg. Our men are all anxious for a fight & confident they can whip the Rebels. The next battle will end the war, one way or the other. If we are defeated, I think the Confederacy will be acknowledged. But if we whip them, they will make peace. God grant the war may soon end.”

Jacob Pyewell, Co. I, 106th Pennsylvania Infantry, 2nd Brig., 2nd Div. II Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S22)

Camp near Falmouth, Virginia, December 10, 1862, to his family.

“We had orders last night to have 3 days rations cooked and in our haversack and be ready to march at a moment’s notice so that don’t look as if we would stop here much longer. To where we will go from here, I cannot tell you but I suppose it will be on towards Frederick[sburg] and from there on to Richmond. From what I can learn, the Rebels are pretty strong at Frederick[sburg] but we will weaken them when we get at them. I think somehow or other that we will go right through to Richmond this time. We will go right through on the fast time this time. I don’t think there is going to be any more skedaddles. I think now we have got the force to put down this rebellion and the right man [Gen. Ambrose Burnsides] at our head and I do believe that he intends to settle this [war] this winter.”

Charles Clarence Miller, Co. D, 140th New York Infantry, 3rd Brig., 2nd Div.; V Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S21)

Camp near Fredericksburg, December 10, 1862, to his parents.

“We are in camp near Falmouth & Fredericksburg is across the river Rappahannock. Last Friday it snowed all day and most all night and it is still on the ground but not as much as it has thawed some and made it very muddy, but today it is pretty warm and I think that the snow will go very fast and if it does, it will be very muddy.

Today they are a giving the boys 60 rounds of cartridges each as tomorrow they say we have to move again but they do not know where but think into winter quarters. That is the reason that we have to get those cartridges for as every man has to have sixty rounds when they encamp for the winter. I think that it is about time that they did move again as we have not got much more wood to burn. If the war lasts two years longer, there won’t be woods left for to make rail fences as we burn all that we can find when we stop.”

John W. Lund, Co. C, 8th New York Cavalry; 1st Brig., Cavalry Div. —Right Grand Division (S&S23)

Belle Plains, Va., December 11th 1862, to his family.

“I wrote a few lines to Lucy some time last month. We were then in Warrenton but our headquarters are now at Belle Plains. It is about 5 miles from Fredericksburg. We are now doing picket duty on the Rappahannock below Fredericksburg. We have not had any fighting since we left Warrenton but we are expecting a large battle in a few days as there is any quantity of rebs on the other side of the river. We have exchanged papers with their pickets and traded sugar and coffee for tobacco as it is a scarce article with them and tobacco with us. I don’t know as I can write anything about the war as you know more about it than we do here. It is not very often that we get a newspaper without our friends send them to us…

We have had some snow here and very cold weather but it is quite pleasant now—but not very pleasant soldiering for we have not had as much as a shelter tent since we came into Virginia. But hard fare will not kill what is left of us or we should have been dead long ago. You wrote that John Balch said he was sick of a soldier’s life. He has not seen any of it yet. Let them follow the 8th Cavalry where they have been for the past three months and they will know something about soldier’s life.”

William Capers Dickson, Co. I, Cobb’s Legion (Cavalry) Battalion (S&S13)

Camp near the Rapid Ann [Rapidan river], December 12th 1862 to his sister

“I cannot find words to express how miserable I was when on opening it I beheld what it contained. I could hardly realize that my dear brother was indeed dead. But I can dwell on the subject no longer. It makes me miserable. The weather is very pleasant at present though there has been snow on the ground for five or six days and it was so cold part of the time that some of the men’s whiskers froze where they breathed on them. There was heavy firing going on yesterday some miles from here, supposed to be at Fredericksburg, and the report has just come in that it was Gen. [J. E. B.] Stuart and that he had blown up the pontoon bridges there and taken three companies of Yankees. I think there is to be an awful battle fought at Fredericksburg and I pray that God may prosper our side. The Yankee force there is suppose to be about two hundred and forty thousand and our force one hundred and twenty thousand. They have the advantage in numbers but God will defend the right.”

During the Battle Letters & Diaries

Samuel Holmes Doten, Co. E, 29th Massachusetts Infantry, 2nd Brig., 1st Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S23)

“Thursday, December 11th—We were ordered at one o’clock this morning to issue cartridges to the men and at 8 o’clock we were in line ready to start. We waited till 4 o’clock p.m. and marched to the banks of the river when we were ordered back again. We pitched some of our tents. Everything had been got ready to leave this place for the other side of the river. At daylight this morning, our batteries opened and were replied to with spirit. We have 140 guns in position and shelled the woods and city. The city was soon on fire in several places and was burning. We laid three pontoon bridges over but with heavy loss and sent over a Brigade but it was then too dark to send more. The Rebels made some good shots at the bridge. Columbus Adams returned to the company today.

Friday, December 12th—Broke camp at about 8 o’clock this morning and took up line of march for the river at 10 o’clock. We crossed over the pontoon bridge at double quick and into the city and formed line of battle. The city is badly riddled with shot and shell. At 3 o’clock p.m. our batteries begun to shell over us and the enemy to reply. Troops have been crossing above and below all day. At 3:30 o’clock p.m. the Rebel batteries got good range of us and dropped their compliments among us. Lieut. Carpenter [Co. H] was wounded in the arm and many shells struck close to us. At sunset the shelling stopped. I found a Secesh flag—a small one. It was in a house that had been shelled. We held our position for the night and laid down on the ground beside our stacks.

Saturday, December 13th—We passed a chilly night. Got breakfast at 7 o’clock and at 9 o’clock formed in line of battle and marched down river. At 9:30 the rebels fired the first gun. It is a good day and pleasant but very smokey. The firing has been very heavy on the right and left flanks and at times the musketry has also been heavy. We are the centre division and stationed in front, close to the banks of the river. At 4 o’clock we were ordered to the left. The Brigade formed in line of battle on the battlefield just within reach of the rebel guns. We remained here ready for action but was not called in. J[ames] L. Pettis of my company was wounded by a rifle shot.

Sunday, December 14th—We started last night at about twelve o’clock and went to the bridge to relieve the Brigade, then on guard. When we got there we found it already done by Gen. Sigel so we marched back to where we started from at daylight, position just to the right of the one near the river under the hill. At 7 o’clock we fired our first gun for the day and was quickly replied to. We soon after marched back to near the bridge and then stood all day in the mud. As the City Mayor’s house was nearby, I went into it. It is terribly shattered and torn to pieces. It was an elegant house and surrounded with beautiful grounds. After dinner I heard that some of the captains of the 18th Mass. Regt. were wounded. Went up to a house nearby that was used for a hospital and found Capts. [William H.] Winsor & Drew of Plymouth, both wounded quite severely. They told me that Capt. Collingwood of Plymouth was also wounded but I could not find him. At night our regiment took position on higher ground and laid down for the night.

Monday, December 15th—This morning the sunrise was bright and clear. We found that our troops on the other side of the river had not been idle through the night but had thrown up four batteries for large guns as we cannot make headway with small guns or light batteries against their entrenchments. It is said that we have 10-inch Columbiads in Battery. If so, we shall soon have music about us. Our plans of operation seem to be Hooker on the right, Franklin on the left, and Sumner in the center. Hooker and Franklin were engaged yesterday and suffered severely and apparently gained nothing. Sumner was also engaged and suffered some with a like result. We have lost from six to eight thousand in killed, wounded, and missing. We have stood to our arms all day ready for any emergency. At about eight o’clock this evening we were ordered to be ready to march and all orders to be given silently as possible. Soon all the troops were moving as they have been ever since dark over the pontoon bridge back to the old camps. All the afternoon the ambulances have been very busy carrying over the wounded. We have orders to bring up the rear and to take up the bridge over the creek, three in number.

Tuesday, December 16th—We succeeded in taking up all the bridges and loading them into boats and as they were outside of our picket line and the pickets taken off. It was dangerous work but we accomplished it by two o’clock this morning and then took up our line of march over the river bridge and back to our old camp where we arrived at three o’clock this morning, tired and wet through with sweat. Thus ends our crossing of the Rappahannock. We did not expect to get much sleep and was not disappointed. At daylight this morning we had rain and having no tent up, we had to get wet. At about 9 o’clock a.m. it cleared away cold. We pitched our tent and tried to dry our clothes. [James L.] Pettis was carried to Washington. [Benjamin F.] Bates, when he found or rather thought we were going into battle, made good time over the bridge to Falmouth. Six batteries have been shelling the rebel’s batteries. What we are to do next is not yet revealed. Quite a number of stragglers left over the other side were taken prisoners this morning. The bridges are all taken up and as far as that is concerned, all is about as it was before.”

Alonzo Clarence Ide, Co. C, 2nd Michigan Infantry, 1st Brig., 1st Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S23)

“Thursday, Dec. 11th—The battle of Fredericksburg has commenced. Our batteries are shelling the town. We have orders to be in readiness to march at 4 in the morning in light marching order.

Friday, Dec. 12th—Time 9 a.m. Our Brigade has just crossed the river. We crossed on the pontoon bridge and are now in Fredericksburg occupying the lower part of the town.

Saturday, Dec. 13th—The ball has opened once more this morning. The fighting so far has been mostly done with artillery.

Sunday, Dec. 14th—Time 4 p.m. This day has been comparatively quiet. There has been more or less cannonading and some skirmishing going on today.

Monday, Dec, 15th—Today as regards fighting has been pretty much like yesterday with but few exceptions.

Tuesday, Dec. 16th—Last night we recrossed the river at about eleven a.m. [p.m.] and now occupy our former camp opposite Fredericksburg.”

Delos Hull, Co. H, 8th Illinois Cavalry, 1st Brigade, Cavalry Division, IX Corps, Right Grand Division (S&S23)

Thursday, December 11th 1862—We were off at the appointed time. Took the road to Falmouth. Went to Gen. Sumner’s Headquarters and was drawn up in line and stood there all day. Our forces commenced to built three pontoon bridges across the river. They made out to get one nearly done when the Reb sharpshooters opened on them from the houses and began to pick off our men who were to work in the bridges. This was a signal for the ball to commence which it did in good earnest and continued for nearly 4 hours when both sides seemed to have a desire to rest a spell for they both ceased firing. It’s so very smokey [like] a fog.

Friday, December 12th 1862—Were routed out at 5 o’clock a.m. and started for Headquarters at 7 o’clock and were drawn up in line & stood there all day. There was not much fighting done—only artillery. There was considerable of that. We returned to Belle Plains at night. The weather was good but it was very smokey. Troops were crossing all day.

Saturday, December 13th 1862—Were routed out at 5 o’clock and started at 7 o’clock for Headquarters. Arrived there at 8 and was drawn up in line. There was a good deal of skirmishing and artillery fighting all the forenoon and about one o’clock it became a general engagement. We were drawn up on a hill where we could see all the movements. It was awful hard fighting. It raged with all the fury imaginable from one o’clock until 7 p.m. when both sides seemed willing to rest for the night. Our loss was much heavier than the enemy’s for they had earthworks and our Boys had nothing to protect them. When the firing ceased we held about the same ground as in the morn. The weather was fine, only it was quite smokey. Gen. [William B.] Franklin captured a battery and a brigade of infantry from the enemy.

Sunday, December 14th 1862—Were routed out at 5. We started at 7 o’clock for Headquarters. Arrived there and were drawn up in line when Cos. E, H, K, and D were detailed to go across the river and relieve Cos. L, I, C, & F who were on picket. Went down to go across the river and as we went over the hill on this side of the river, the Rebs saw us and began to shell us which they kept up pretty lively until we got across. We had to go about one mile to the right of Fredericksburg (up the steam nearly opposite of Falmouth) where we found them. Our line of pickets were only half a mile from the enemy’s batteries and right out on the flat in plain sight where if more than two of us got together, they would throw a shell at us. The pickets were not more than 70 or 80 rods apart. The weather was very warm and nice although a little smokey. There was not much fighting—only the artillery and a little skirmishing with the pickets. Our [men] were getting up their wounded all day.

Monday, December 15th 1862—We remained on picket all day. No. fighting except a few shots exchanged between the batteries. Spent most of the day in searching the houses to see what we could find. There were two splendid houses and the residence of Mrs. Ann E. Fitzgerald. The other a Mr. Hoover (I believe) in the latter was left a splendid piano and in fact in both of them nearly all the furniture was left. Weather clear.

Tuesday, December 16th 1862—Were routed out at about 3 o’clock and ordered to pack up and mount which we did and came down to the bridge to come across the river and found the artillery and infantry all moving. They seemed to be recrossing the river. We recrossed and came to [camp]. We remained in camp all day. No forage for our horses. We got all of two quarts of oats.

Joshua H. Tower, Co. F, 1st Massachusetts Heavy Artillery (S&S23)

Fort DeKalb [Arlington, Height’s Va.], December 13, 1862, to his sister.

“There is a battle being fought at Fredericksburg about sixty miles from here and about half way between here and Richmond. The papers say it will be the bloodiest battle of the century. Already there are five thousand sick and wounded in the hospitals from that fight. The Union forces under Gen. Burnside have got possession of Fredericksburg and are driving the rebels out of their fortifications but it will cost seas of blood to do it and then they will retreat into other fortifications to be still driven, unless some fortunate circumstance shall give us Richmond while Burnside is engaging the rebels at Fredericksburg.

17th. Since writing the above, news has arrived that Gen. Burnside has retreated across the Chickahominy [Rappahannock] and abandoned the fight after losing ten thousand men killed, wounded and missing. Burnside, in his dispatch to the general government, says he felt that the enemy’s works could not be carried and that a repulse would be disastrous to his army. Finally, I can’t tell anything about it when the war will end or which will come off victorious, but hope we shall come [out] top of the heap.”

John Boultwood Edson, Co. E, 27th New York Infantry, 2nd Brig., 1st Div., VI Corps—Left Grand Division (S&S23)

On the Battlefield of Fredericksburg, December 13th [1862], to his father.

“This is the second night that we have bivouacked upon the battlefield. The enemy is in strong position before us. We crossed in force yesterday morning the night before after our forces had finished shelling the city. Our regiment was ordered over & deployed as skirmishers and scour the country a short distance in front after which we returned across the river. The next morning—yesterday I mean—the whole Left Grand Division crossed. Our position is near the center. Our lines is about 10 miles long so you may judge of the quantity of ground we cover and have to fight over. Our brigade lay under the fire of the rebel batteries all day. Tomorrow we take the front as skirmishers. I may fall. It is a hard contested field. It is (nip & tuck) with both sides so far although I believe the advantage if any is with Stonewall Jackson. I hear [he] commands the rebels.

We attacked them on the left this forenoon with a view of flanking them but did not make much headway. They have a very strong position. The troops have to spend the night in the open air & tonight are not allowed to unpack their knapsacks. This order is that we may be ready to support the skirmishers in case they are being driven in…I will now close this as I write under some difficulties sitting upon my knapsack & it upon the ground. The Rebel campfires are only a little over half a mile distance. So goodbye. If we meet no more here below, may we meet in a far better world where war & conflict is not thought of. May God defend the right is the sincere prayer of your son…”

Herbert Daniels, 7th Rhode Island Infantry, 1st Brig., 2nd Div., IX Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S22)

Fredericksburg, Virginia [14 December 1862] Sunday Morning 10 o’clock, to his friend.

“There has been a great battle & Percy & I were in it but we were not hurt. The mail is going in a few minutes so I can’t write much. Lieut. [George A.] Wilbur was hit in the leg—not very bad. Mr. [Harris C.] Wright [of Co. B] was badly wounded. I can’t find out whether he is alive or not. He was rather rash, went up with the Colonel to the front while the rest of us were lying down. Thursday they shelled the city all day but we did nothing but look on. Friday forenoon we entered the city and stayed all day & night until yesterday noon when we went in the field and stayed till dark, lying down behind a hill except when we stood up to fire. The Colonel [Bliss] said the fire was as hot as men were ever exposed to. Only 18 men of our company & 14 of Percy’s could be found at night and yet there was but 1 known to be killed. Not a man in the regiment ran away or flinched. [Lieut.] Col. [Welcome Ballou] Sayles was killed instantly. We shall miss him very much. I don’t believe we shall go into battle again today.”

Josiah R. Kirkbride, Co. C, 23rd New Jersey Infantry, 1st Brig., 1st Div., VI Corps—Left Grand Division (S&S23)

Near Fredericksburg, [Virginia], December 14, 1862, to dear ones at home.

“I have half hour to write in. Yesterday we were in a very heavy battle for about two hours. I came out safe and sound. There is a few out of our company wounded. They are Capt. [Samuel] Carr in the foot, Alonzo [Moorehead] Bodine in the back, and one or two others. There is a very heavy battle here and we do not know when it will stop. We may soon be in it again but we are getting the best of them. We were in one of the heaviest [fights] ever was seen. The shells bursted all around us but I am safe. Give my love to all. So goodbye for the present. Pray for me.”

Austin Doras Fenn, Co. H, 10th Vermont Infantry (S&S22)

[Rockville, Maryland-, December 14, 1862 to his wife.

“…The last news we have got here from Burnside [at Fredericksburg,] he was driving the rebels right along. He won’t when he has drove the rebels out of one place have to sit on his ass six weeks to talk about it. I believe he will have Richmond by New Years.”

Theodore Harmon, Co. I, 153rd Pennsylvania Infantry, 1st Brig., 1st Div., XI Corps—Reserve Grand Division (Harman’s Civil War Letters)

[Camp] Dumfries, Virginia, December 14, 1862, to his wife.

“And now I must let you know that we had a very hard march and hain’t done marching yet. We have marched now for days through the mud and dirt till over our shoes. That was the hardest job that I ever had but this morning I feel good. I am ready for another march and I think we will march off very shortly. I thought we would take off already but we wait for our rations. They are all we just got two crackers and one pound of steak for one day and that was rare but the men ate it raw. But I can’t do that. I just threw my steak in the fire till it was roasted, then I ate it. I tell you, Louisa, soldiering is a hard life but I like it better than I did. I think we will be down in Fredericksburg tomorrow. Then we will have some fighting to do. But that is just what I like.

I seen more soldiers this morning than I ever seen [before]. They are all moving down to Fredericksburg. They’ve been marching through this place since this morning daylight but I think we will start pretty soon too and I think they are about 30 thousand of soldiers that camped here last night and they are all going down to Fredericksburg. And if we are all down, they are about three hundred thousand soldiers there.”

John Boultwood Edson, Co. E, 27th New York Infantry, 2nd Brigade, 1st Div., VI Corps—Left Grand Division (S&S23)

Still on the Battlefield, Monday morning, December 15th [1862] to his father.

“Yesterday all day we were on picket and had to lay under their fire all day. Whenever we would put up our heads, they would pop at us. The Rebs are very strongly fortified. It will be a great sacrifice of lives to take their position. Yesterday being Sunday, they did not commence on either side.”

George Everett White, Co. K, 120th New York Infantry, 2nd Brig., 2nd Div., III Corps—Center Grand Division (S&S10)

On the Battlefield, December 15, 1862 to his father.

“We came on the field Saturday. Have laid under fire ever since. We expect to have a fight any moment. The Rebs are in the woods about 25 rods in front. I have not time to write. Much the most is just going out. ‘Tis a big fight, this being the 3rd day. We are alright yet. Nobody hurt in our regiment. We are in the extreme front. Will write more at the close up etc. of the battle. We are in Sickles Division, Gen. Hall’s Brigade. The dead and wounded lie around very thick. Can’t write any more.”

Edson Emery, Co. E, 2nd Vermont Infantry, 2nd Brig., 2nd Div., VI Corps—Left Grand Division (S&S19)

Battlefield Fredericksburg, Va., December 15, 1862 to his Mother.

“This is the first opportunity I have had to write you. This is the fifth day of the fight here. Saturday our regiment was engaged. We lost about 60 men in killed & wounded. Our company had four wounded—no one that you knew except Fred Chamberlain. He was only slightly wounded. We was very fortunate. We was under a terrible fire. The great share of the fighting has been with artillery but we expect hard infantry fighting before it is over, The whole Rebel Army is here & they have great advantage in position. They are protected on a high hill. Our line is about six miles long. We are now waiting for our reserves to come up. Then I suppose we shall try to carry their works. Philo is well & tough. Our regiment done splendidly in the fight, so our Generals say. It is fine weather now.”

Edgar A. Burpee, Co. I, 19th Maine Infantry, 1st Brig., 2nd Div., II Corps—Right Grand Division (S&S23)

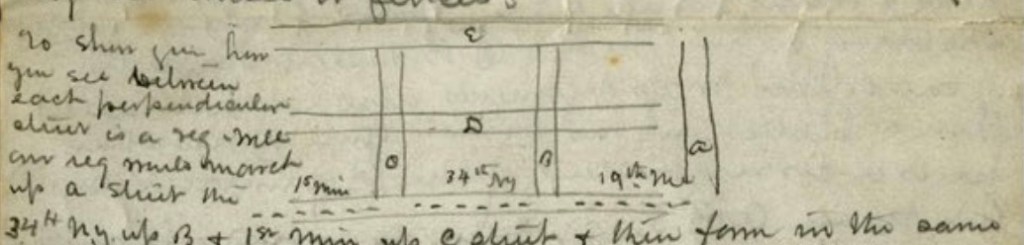

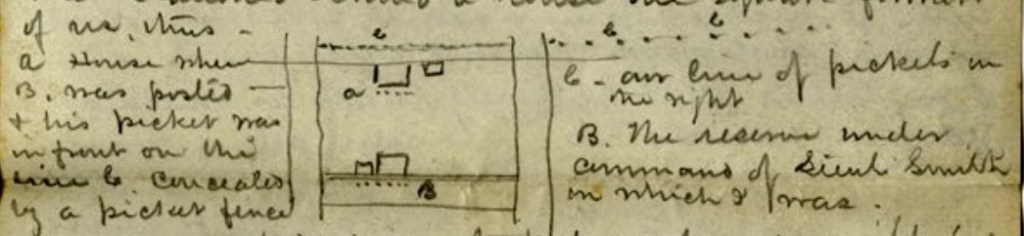

Fredericksburg [Virginia], December 15th 1862, to his father. [Includes several sketches]

“Have just sent you a few lines stating we had gained possession of this city and I was yet safe. While waiting for our troops to get arranged properly for an advance, I will commence to you a statement of what has occurred since I wrote you while on picket. We were relieved from picket at about 7 o’clock in the eve and after a march of 1.5 hours reached our encampment which, by the way had been moved to a hill a short distance from the one we had occupied two days before. After pitching tents, and building fires, we commenced anew to enjoy ourselves. This was Wednesday evening and while sitting by our fire—for I tented with the Lieutenants—who should approach us but Geo. Green of our city on his way to see Edward. We were very glad to see him and our tongues were busy enough talking about Rockland people and news. We had him sleep with us that night and he will tell you about what transpired so I will not pause here to write about it.

At about 2 o’clock, Lieut. [Gershom F.] Burgess was summoned to the Colonel’s quarters and when he came back he reported that we had received orders to march in the morning at 6 o’clock with our rations and blankets but not knapsacks & other baggage must be left behind, and all our preparations must be made quietly. Being acting orderly, I summoned the company at 4 o’clock and gave them the orders and all immediately commenced operations. At the appointed hour we were in the line and took up our line of march down the hill to the plain and found our whole corps in motion & when our place in the line approached, we found them. Let me say, however, that at about 5:30 o’clock, while we were busy at our work, the report of a gun was heard which rolled through the morning air like a deep roar of the thunder. This was a signal gun and to us indicated that something was in the process of being done. At 6 another was heard and immediately after the rattle of musketry and some other guns intertwined with musketry from our forces at the river engaged in laying the pontoon bridge.

We marched with our Corps about a mile near the river and on a plain between the two hills stacked arms and lay down awaiting the order to move forward. We were here waiting for the pontoon bridge to be laid so we could cross. This was done by the Engineer Corps supported by the advance of our division (our division being in the advance of the whole corps). All this time the guns of both forces were constantly being fired and such a roar I never heard before. It seems as if the very heavens were filled with thunder and it was striving to see how much noise it could make. We found afterward that our force were engaged in shelling the city.

About 4 o’clock we moved forward toward the city and came upon the river bank amidst the dropping of rebel shells, and at double quick crossed the pontoon bridge & set foot in the doomed city for the first time. We filed out into the street that runs along the river’s bank, having the honor of being the first regiment of our brigade in which was the 7th Michigan & 16th Massachusetts had preceded us, and as we entered, ran up the street some 5 or 6 rods in the advance of us skirmishing and the bullets of the rebs came whistling thickly over our heads and into our midst.

When we first enter the city, you come upon the river’s bank which gently rises from its edge and extends to the middle of the place & then descends again so the city sits upon a hill. Its streets are laid out in regular squares (I shall draw you a plan as soon as I can). Some skirmishing going on in the next street above us. The men nicely protected from the rebel shots.

When the pontooniers commenced to lay the bridge, the rebs kept silent till they had laid about 6 rods & then from the houses & the guard house marked [on sketch], their sharpshooters rapidly picked off the men This was a trying time. Every man who stepped out to do anything was of course a mark. The 7th Michigan being at supporting distance was ordered to cross in boats. No one seemed willing to run the risk. Gen. Burnside addressed them saying he wanted the men to cross & appealed to their patriotism &c. (so report says) when they immediately volunteered to go. After taking a drink of whiskey, the boats pushed off and in a few minutes touched the other shore notwithstanding the rebel shots from this city. The first man who landed fell dead & some of the others were wounded but ashore the rest went & soon after others and a struggle for the mastery began which ended in our gaining the ground.

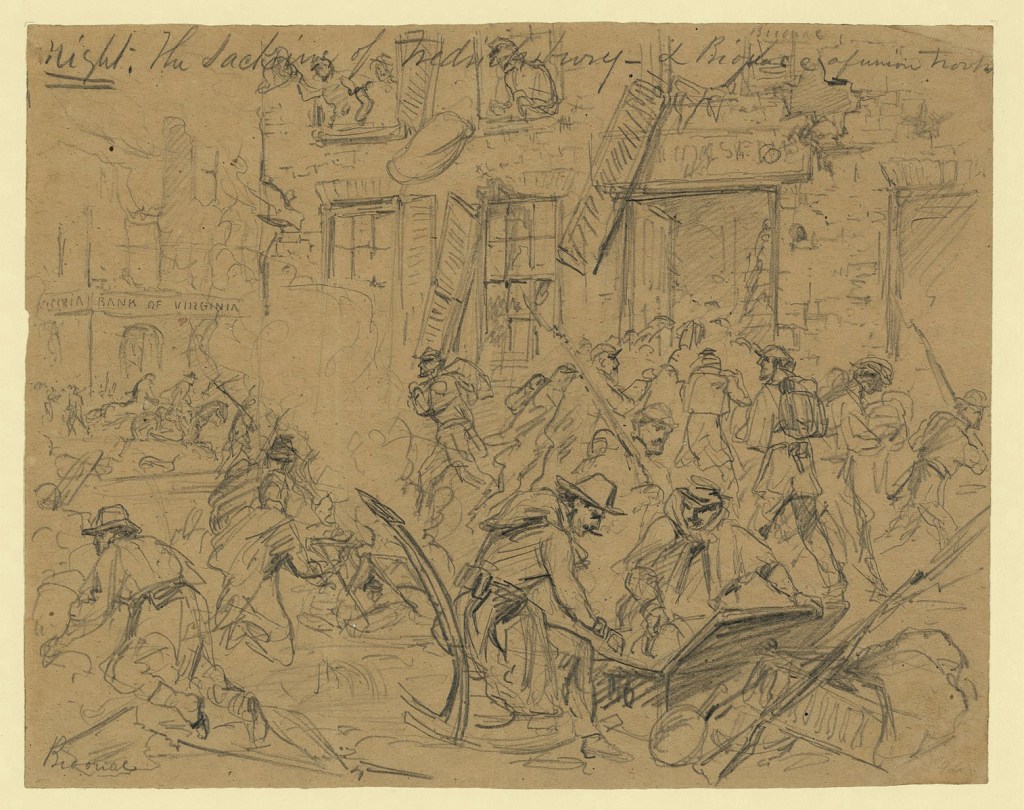

Our batteries too poured into the Rebels showers of shell so that they completely riddled the houses nearby killing a large number of the enemy. Several houses were at this time on fire having been set by our shells and as it was near dark, the light of them aided us in our operations. The men were ordered to remain in this street till morning and make themselves as comfortable as possible. By 7 o’clock the firing had nearly ceased and our pickets were thrown up the street when our men commenced to making themselves comfortable by ransacking the houses and stores, tearing down fences and out buildings. In 15 minutes after they commenced, the street was filled with soldiers running to and fro, loaded with boards, beds and bedding and clothes of all descriptions, crockery ware and household furniture, tobacco, bee hives, flour, sugar, and every variety of goods from apothecary, dry goods, grocery, liquor, and jewelry, stoves. It was amusing though sad scenes were occurring around us, to see the different acts, faces & attitudes of the men & hear their expressions. One fellow came out of a house dressed up in women’s clothes & his queer pranks caused a great deal of merriment. Eatables were freely distributed and fires being built them men commenced to cook their suppers.

The old regiments declared thy never lived as before. Everything was in abundance, so much so that it was hard to give away many kinds of articles. Bread and flapjacks with honey & preserves were quickly made and devoured. Every pocket was filled with tobacco or some trinket or other. Our haversacks were well stoved with some article of food and most of us had a good bed with a prospect of a night of rest. The men seemed wild with joy, yet found so many things they would love to carry with them they seemed almost frantic because they had no place to put them.