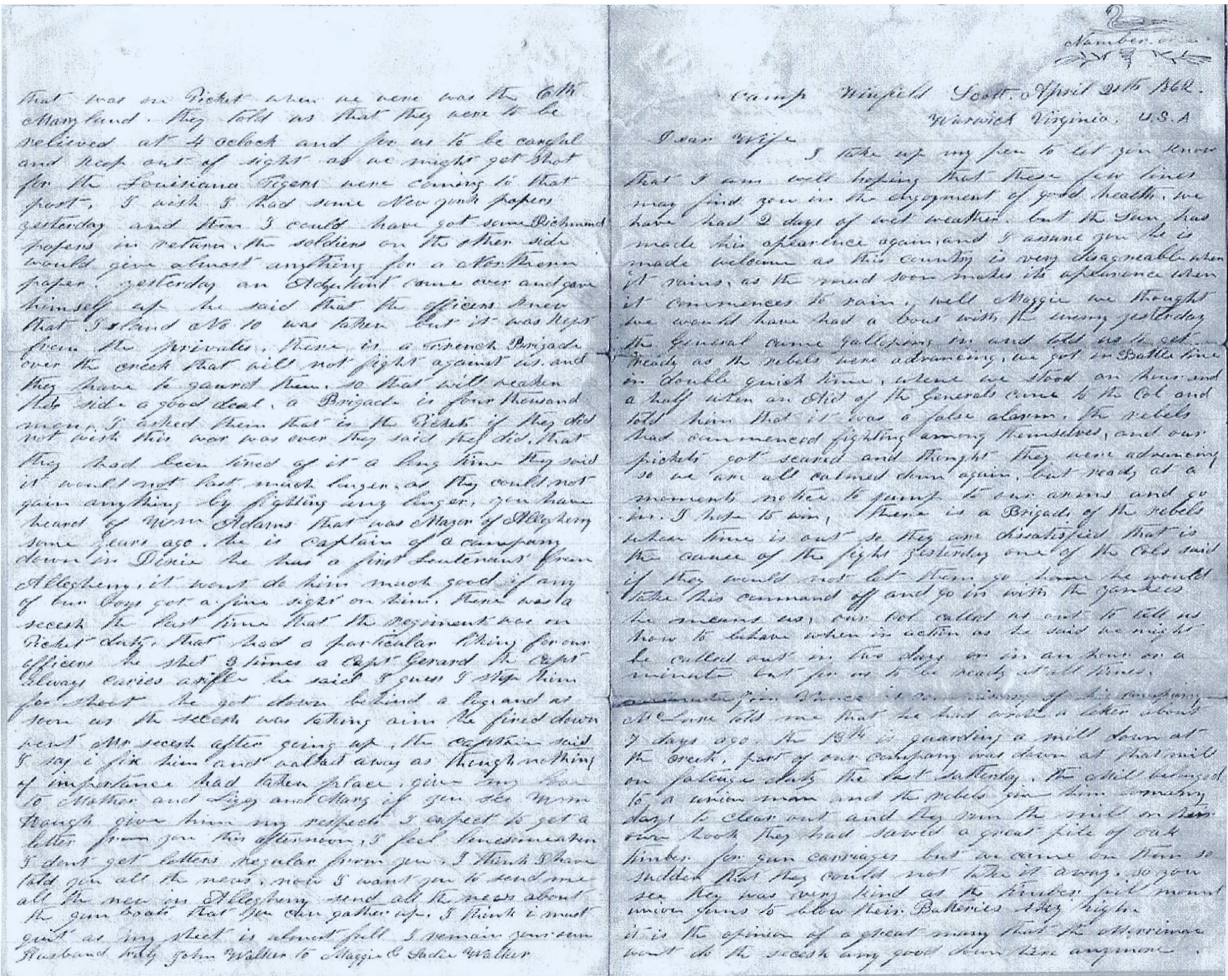

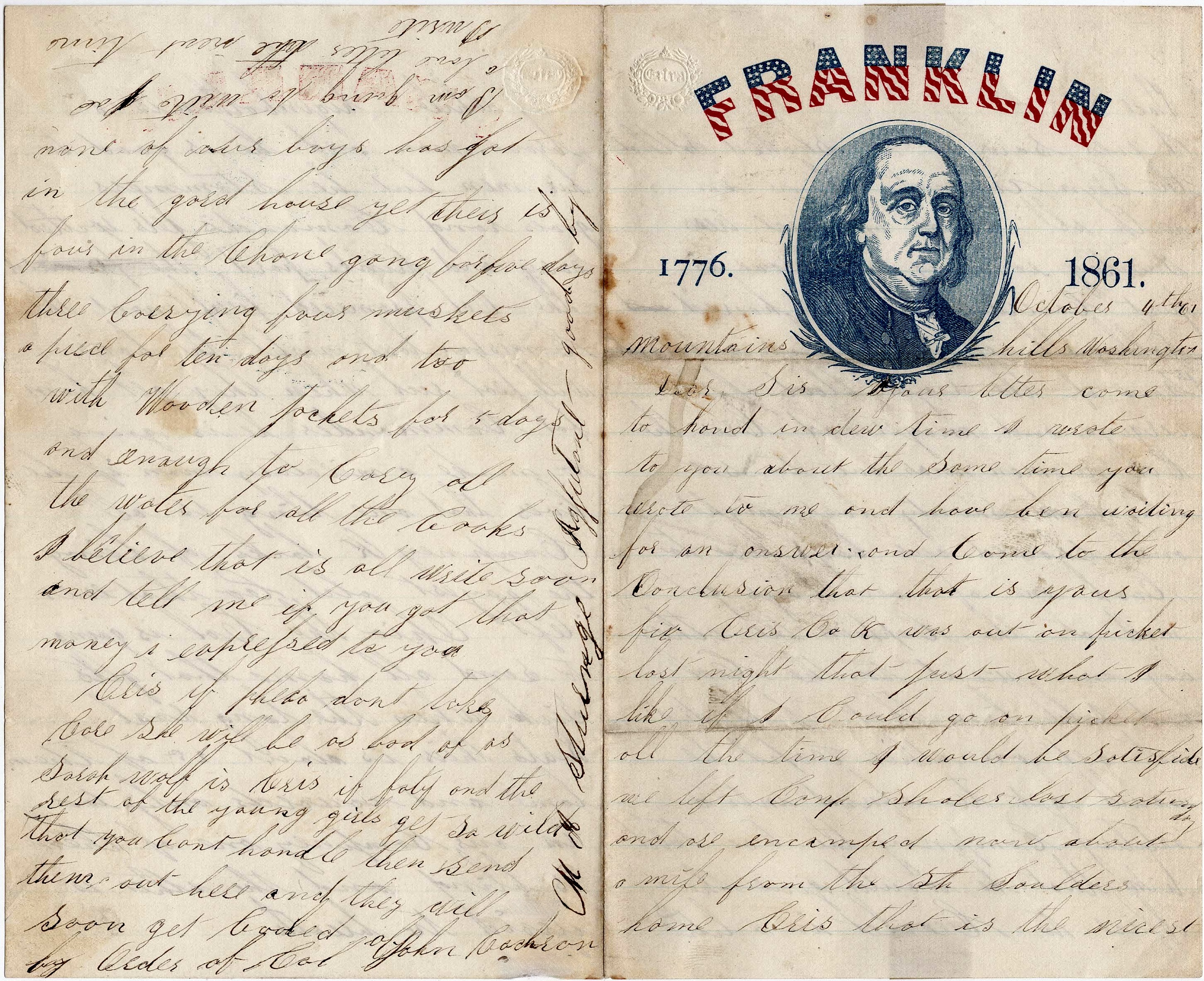

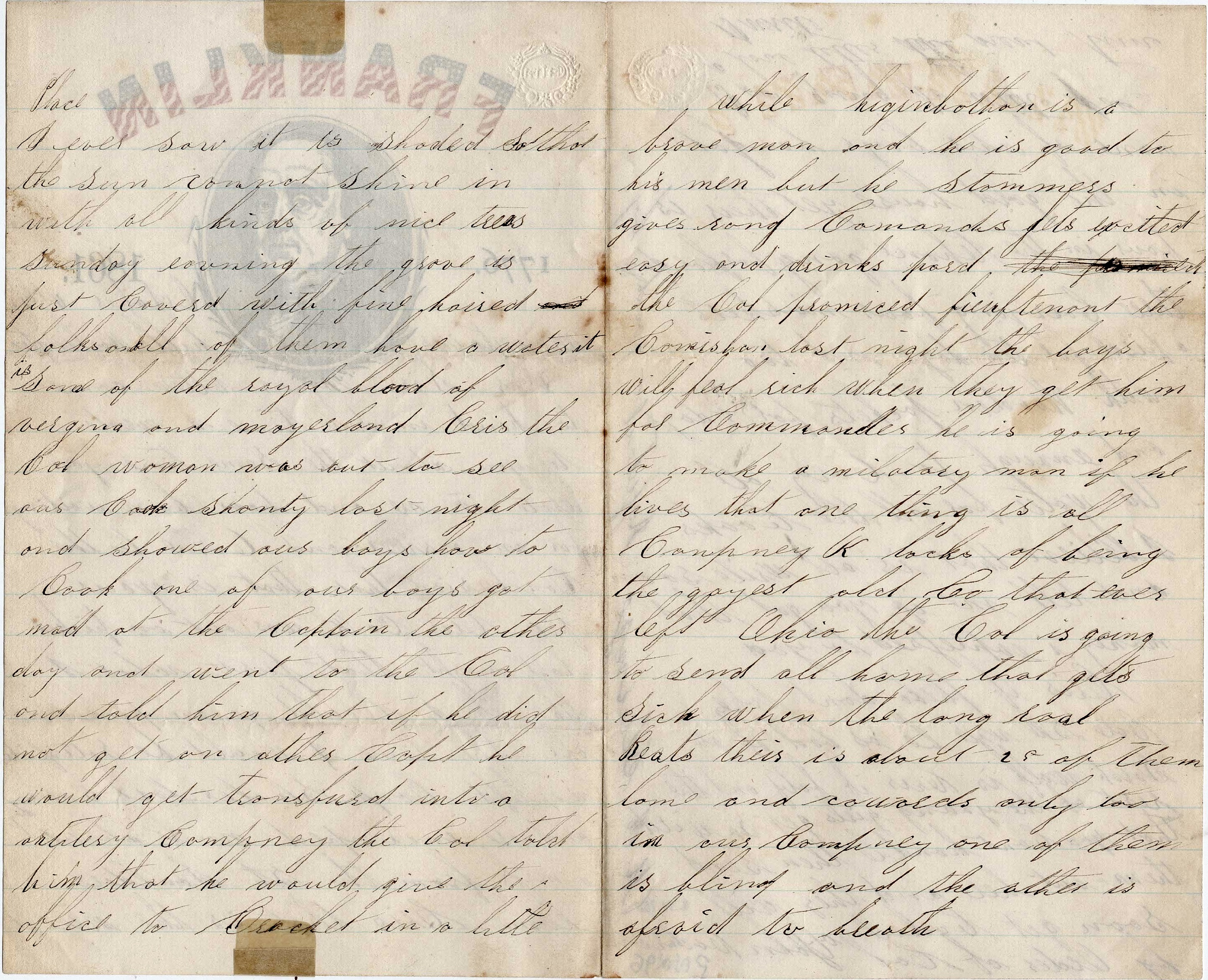

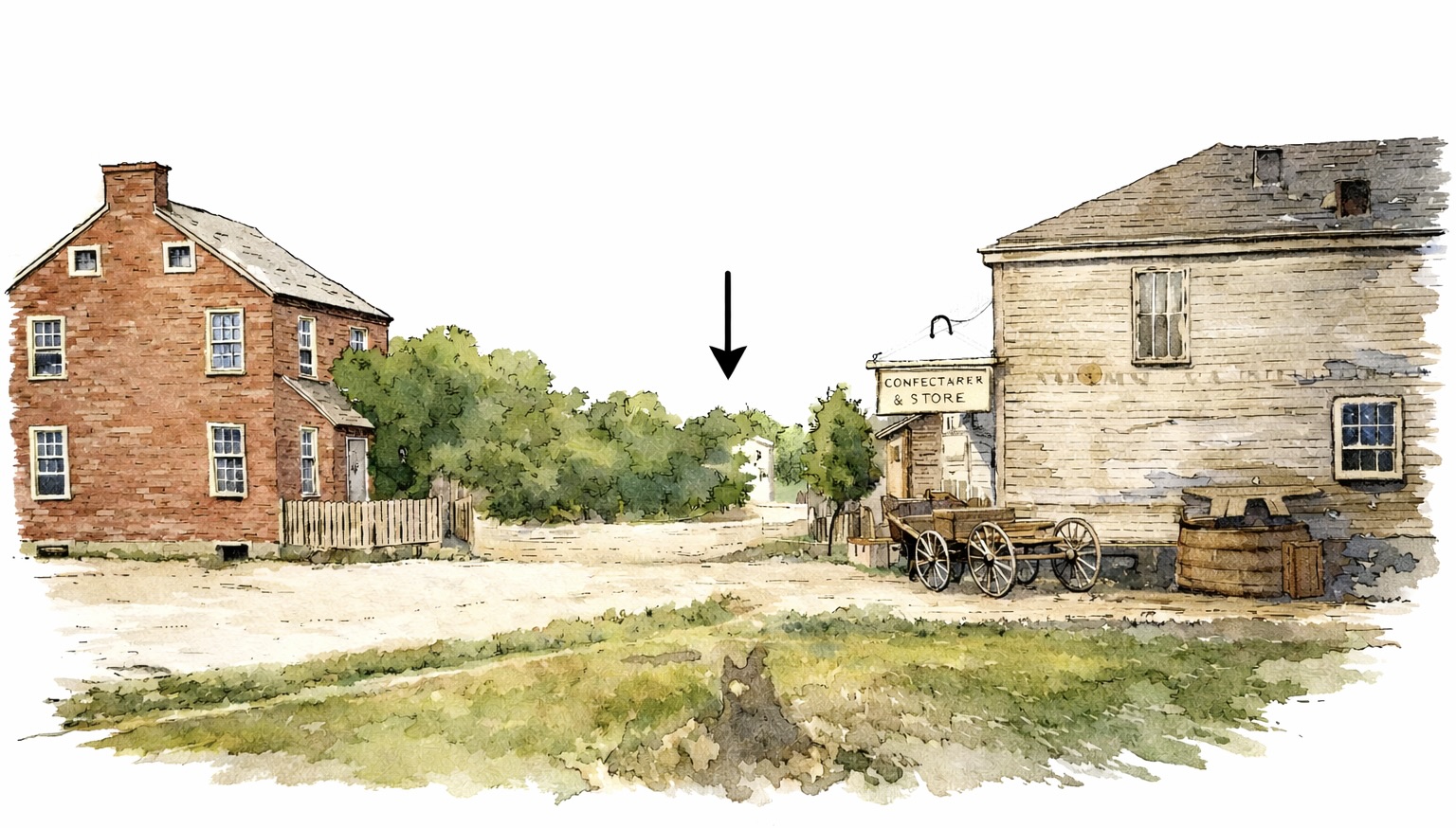

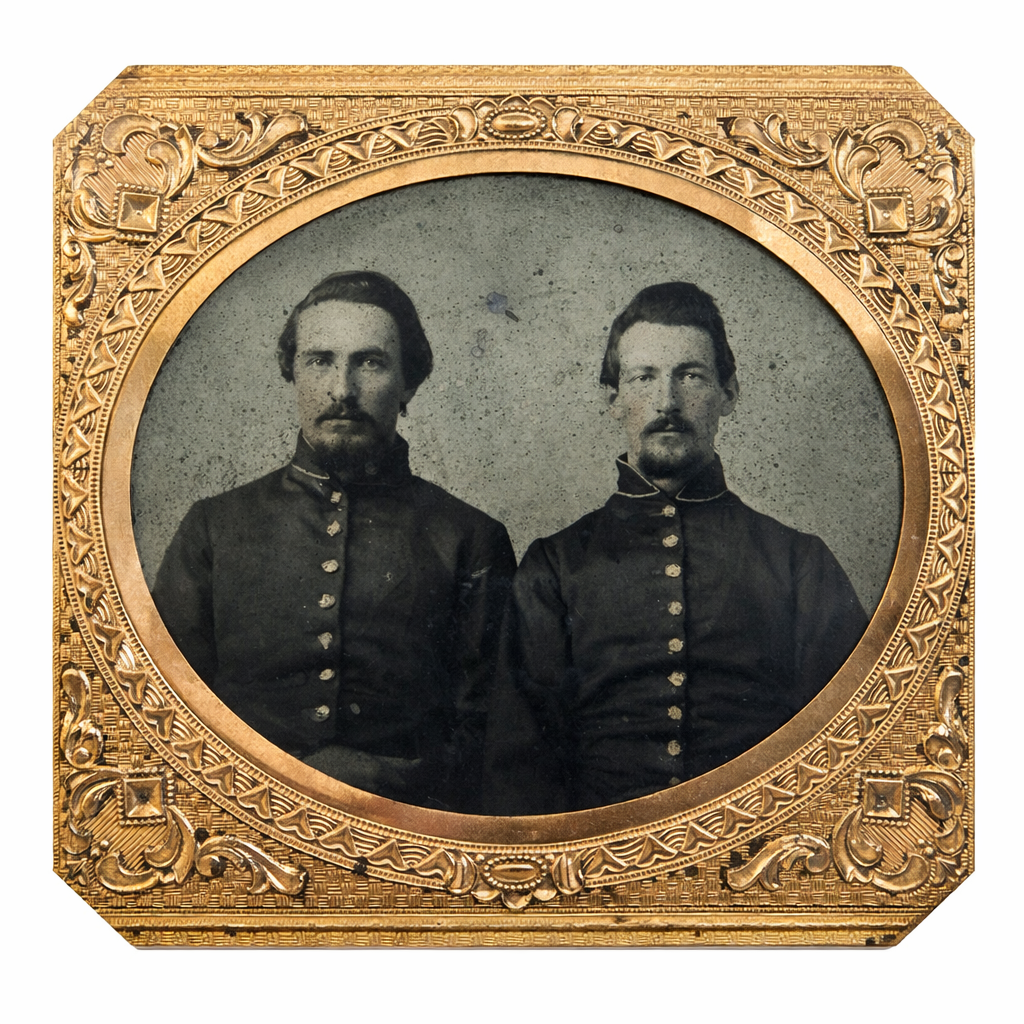

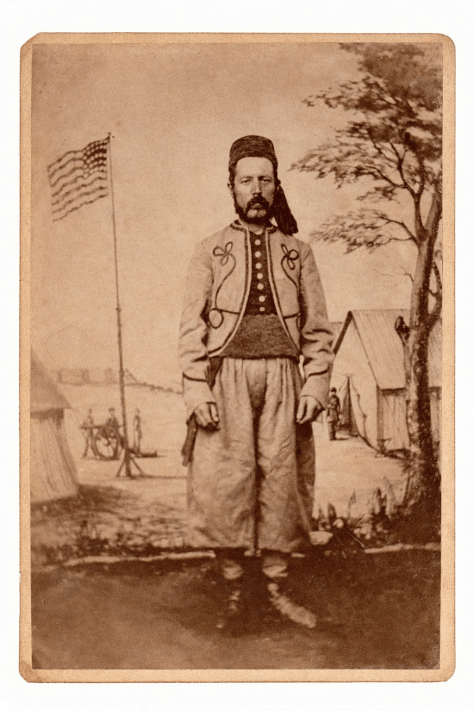

John Walker (1834-1862) was earning his living as an ice dealer in Allegheny City when he enlisted in Co. F, 61st Pennsylvania Infantry on 1 August 1861. By the end of October he was mustered in as a private at Camp Advance, Virginia, with the rest of his regiment. His tombstone in Union Dale Cemetery, Pittsburgh, informs us that his parents were Joseph Walker (1801-1863) and Elizabeth Smith (1802-1884). It also informs us that both he and his older brother, William S. Walker (1824-1862) were both killed in the Battle of Fair Oaks on 31 May 1862. What it does not reveal, however, is the fact that when Walker left home, he left behind a wife, Margaret M. (Black) Walker (1835-1939) and a young daughter, Sadie Valentine Walker (1859-1948).

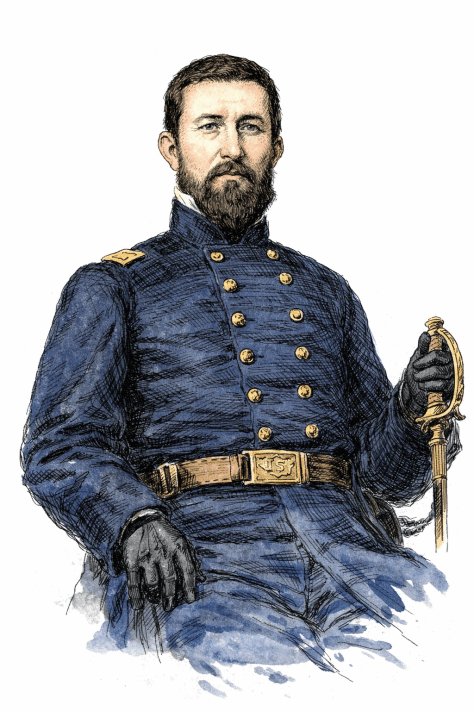

The 61st Pennsylvania was organized at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in August 1861 and mustered in for a three year enlistment under the command of Colonel Oliver H. Rippey who was killed in the Battle of Seven Pines, where the regiment was left without a field officer standing. During the siege of Yorktown, the regiment was part of the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, IV Army Corps which was commanded by Brig. Gen. Charles D. Jameson.

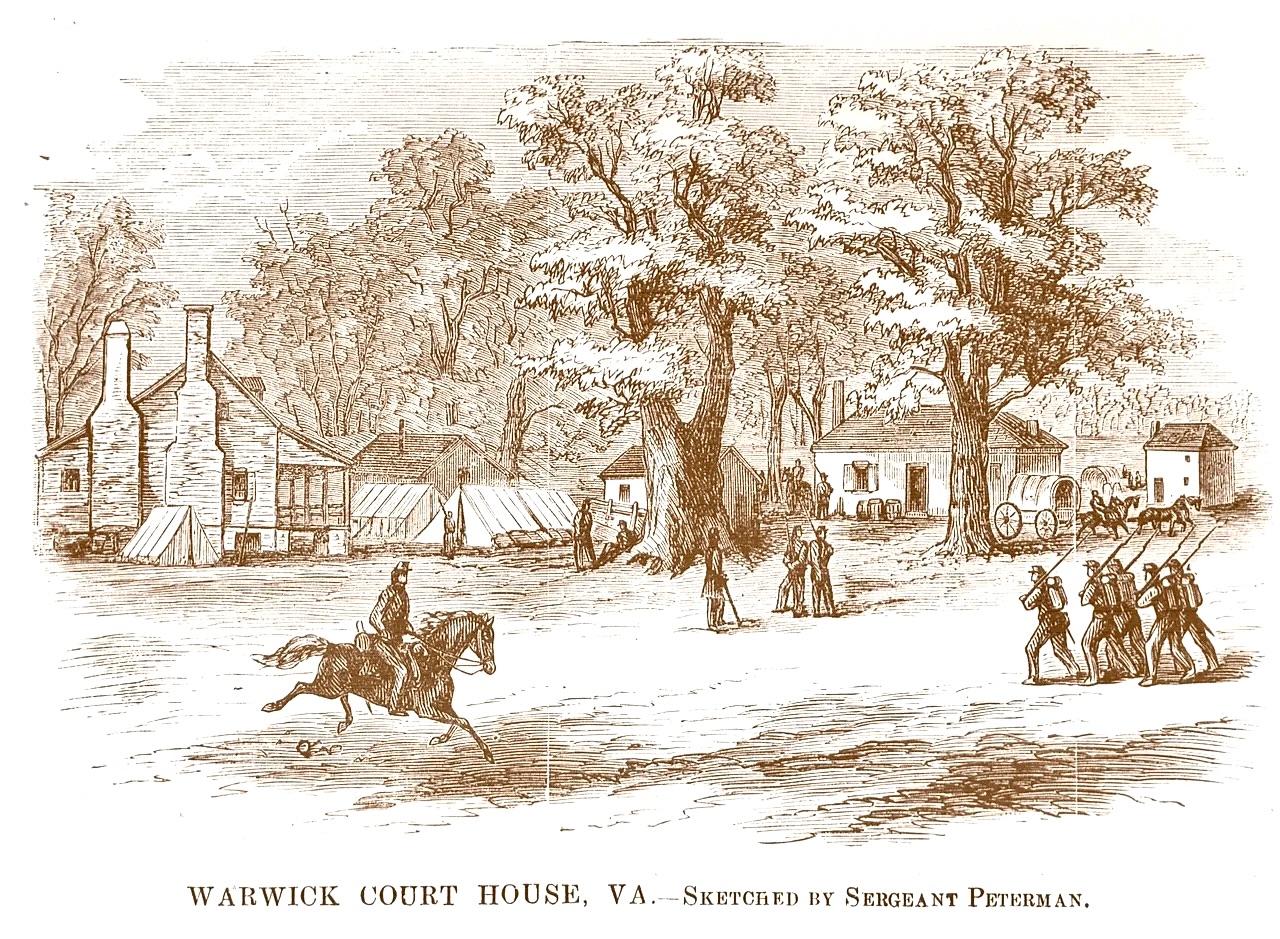

Walker’s letter to his wife gives us news of the regiments activities during the last full week of April 1862 near Warwick Court House where they had been since April 6th. The pickets of the 61st Pennsylvania were the first to enter the Confederates’ deserted works on May 4, 1862.

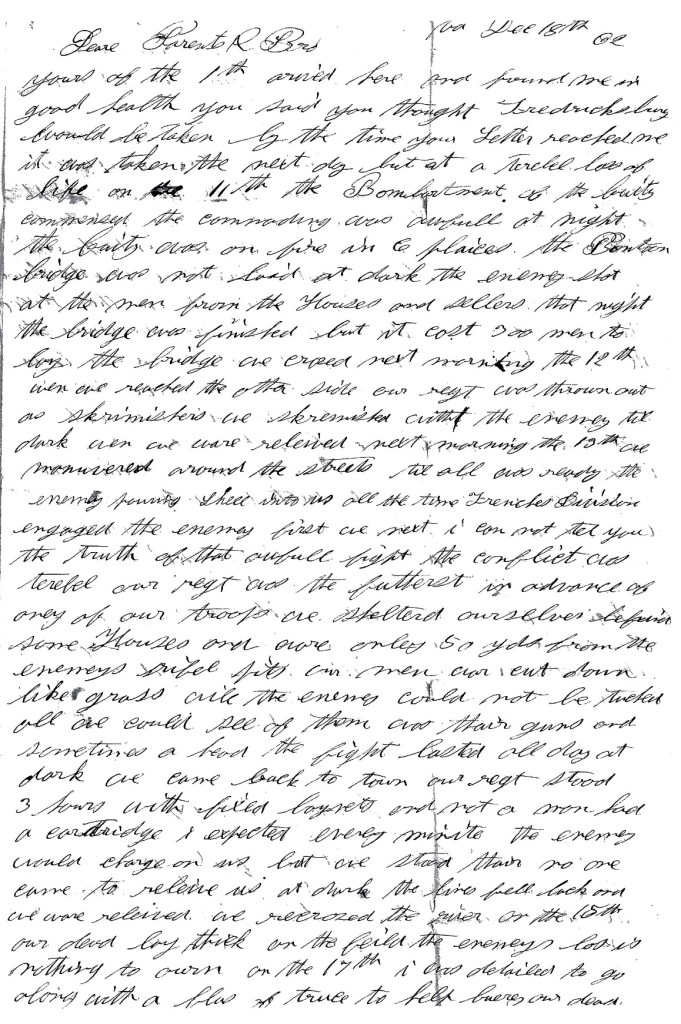

[Note: This letter is from the private collection of Keith Fleckner and was offered for transcription and publication on Spared & Shared by express consent.]

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Camp Winfield Scott

Warwick Virginia, U.S.A.

April 20, 1862

Dear Wife,

I take up my pen to let you know that I am well, hoping that these few lines may find you in the enjoyment of good health. We have had 2 days of wet weather, but the sun has made his appearance again, and I assure you he is made welcome as this country is very disagreeable when it rains, as the mud soon makes its appearance when it commences to rain.

Well Maggie, we thought we would have had a bout with the enemy. Yesterday the General came galloping in and told us to get ready as the rebels were advancing. We got in battle line in double quick time where we stood an hour and a half when an aide of the General’s came to the colonel and told him that it was a false alarm. [It seems] the rebels had commenced fighting among themselves and our pickets got scared and thought they were advancing. So we are all calmed down again but ready at a moments notice to jump to our arms and go in—I hope to win. There is a brigade of the rebels whose time is out so they are dissatisfied. That is the cause of the fight yesterday. One of the colonels said if they would not let them go home, he would take his command off and go in with the Yankees—he means us.

Our colonel [Oliver Hazard Rippey] called us out to tell us how to behave when in action as he said we might be called out in two days or in an hour or a minute, but for us to be ready at all times.

John Vance is commissary of his company. McLane told me that he had wrote a letter about 7 days ago. The 13th is guarding a mill down at the creek. Part of our company was down at that mill on fatigue duty the last Saturday. The Mill belonged to a Union man and the rebels give him so many days to clear out and they run the mill on their own hook. They had sawed a great pile of oak timber for gun carriages but we came on them so sudden that they could not take it away, so you see they was very kind, as the timber will mount Union guns to blow their batteries sky high. It is the opinion of a great many that the Merrimac won’t do the secesh any good down here anymore.

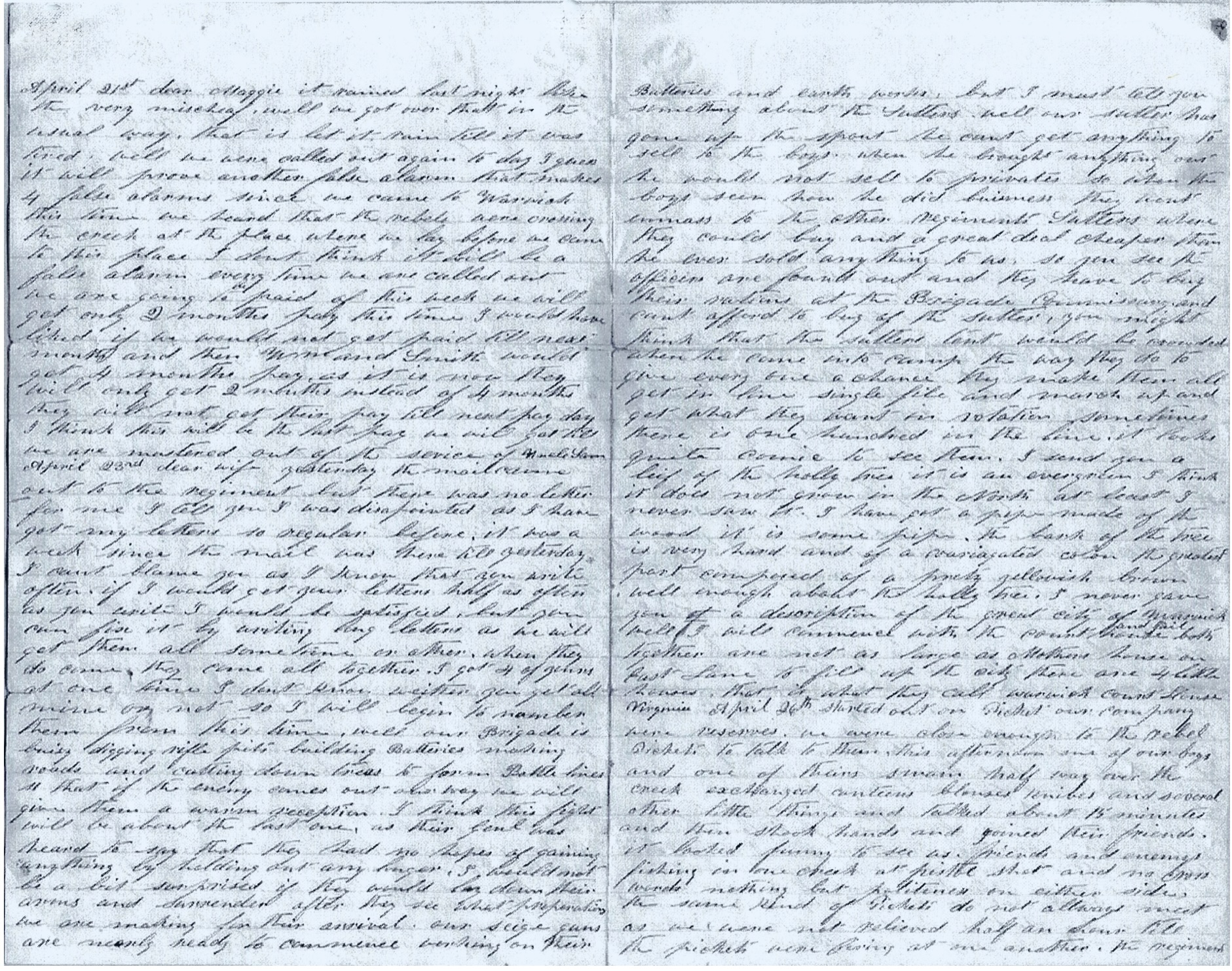

April 21st. Dear Maggie it rained last night like the very mischief. Well we got over that in the usual way—that is, let it rain till it was tired.

Well we were called out again today. I guess it will prove another false alarm. That makes four false alarms since we came to Warwick. This time we heard that the rebels were crossing the creek at the place where we lay before we came to this place. I don’t think it will be a false alarm every time we are called out.

We are going to be paid off this week. We will get only two month’s pay this time. I would have liked if we would not get paid till next month and then William and Smith would get four months pay. As it is now, they will only get two months instead of four months. They will not get their pay till next pay day. I think this will be the last pay we will get till we are mustered out of the service of Uncle Sam.

April 23rd. Dear wife, yesterday the mail came out to the regiment but there was no letter for me. I tell you I was disappointed as I have got my letters so regular before. It was a week since the mail was here till yesterday. I can’t blame you as I know that you write often. If I would get your letters half as often as you write, I would be satisfied. But you can fix it by writing long letters as we will get them all sometime or other. When they do come, they come all together. I got four of yours at one time. I don’t know whether you get all mine or not so I will begin to number them from this time.

Well, our brigade is busy digging riffle pits, building batteries, making roads, and cutting down trees to form battle lines so that if the enemy comes out our way, we will give them a warm reception. I think this fight will be about the last one as their general was heard to say that they had no hopes of gaining anything by holding out any longer. I would not be a bit surprised if they would lay down their arms and surrender after they see what preparations we are making for their arrival. Our siege guns are nearly ready to commence working on their batteries and earth works.

But I must tell you something about the sutlers. Well our sutler has gone up the spout. He can’t get anything to sell to the boys. When he brought anything out, he would not sell to privates, so when the boys seen how he did business, they went enmasse to the other regiments’ sutlers where they could buy and a great deal cheaper than he ever sold anything to us. So you see the officers are found out and they have to buy their rations at the brigade commissary and can’t afford to buy off the sutlers. You might think that the sutler’s tent would be crowded when he came into camp. [But] the way they do to give every one a chance, they make them all get in line single file and march up and get what they want in rotation. Sometimes there is one hundred in the line. It looks quite comic[al] to see them.

I send you a leaf of the holly tree. It is an evergreen. I think it does not grow in the North—at lease I never saw it. I have got a pipe made of the wood. It is some pipe. The bark of the tree is very hard and of a variegated color, the greatest part composed of a pretty yellowish brown. Well, enough about the holly tree.

I never gave you a description of the great city of Warwick. Well, I will commence with the court house and jail. Both together are not as large as mother’s house on East Lane. To fill up the city, there are four little houses. That is what they call Warwick Court House, Virginia.

April 26th. Started out on picket. Our company were reserves. We were close enough to the rebel pickets to talk to them. This afternoon, one of our boys and one of theirs swam halfway over the creek, exchanged canteens, blouses, knives, and several other little things and talked about 15 minutes and then shook hands and joined their friends. It looked funny to see us, friends and enemies, fishing in one creek at pistol shot and no cross words—nothing but politeness on either side. The same kind of pickets do not always meet as we were not relieved half an hour till the pickets were firing at one another. The [rebel] regiment that was on picket when we were was the 6th Maryland. 1 They told us that they were to be relieved at 4 o’clock and for us to be careful and keep out of sight as we might get shot for the Louisiana Tigers 2 were coming to that post. I wish I had some New York papers yesterday and then I could have got some Richmond papers in return. The soldiers on the other side would give almost anything for a Northern paper. Yesterday an adjutant came over and gave himself up. He said that the officers knew that Island No. 10 was taken but it was kept from the privates.

There is a French brigade over the creek that will not fight against us and they have to guard them so that will weaken their side a good deal. 3 A brigade is four thousand men. I asked them—that is, the pickets—if they did not wish this war was over. They said they did—that they had been tired of it a long time. They said it would not last much longer as they could not gain anything by fighting any longer.

You have heard of William [B.] Adams 4 that was Mayor of Allegheny some years ago? He is captain of a company down in Dixie. He was a first lieutenant from Allegheny. It won’t do him much good if any of our boys get a fine sight on him. There was a secesh the last time that the regiment was on picket duty that had a particular liking for our officers. He shot three times at Capt. [Joseph] Gerard [of Co. K]. The captain always carries a rifle. He said, “I guess I’ll stop him for shooting [at me].” He got down behind a log and as soon as the secesh was taking aim, he fired. Down went Mr. Secesh. After getting up, the captain said, “I’d say I fixed him,” and walked away as though nothing of importance had taken place.

Give my love to Mother and Suzie and Mary. If you see William Hough, give him my respects. I expect to get a letter from you this afternoon. I feel lonesome when I don’t get letters regular from you. I think I have told you all the news. Now I want you to send me all the news in Allegheny. Send all the news about the gunboats that you can gather up. I think I must quit as my sheet is almost full. I remain your own husband truly, — John Walker

to Maggie & Sadie Walker

1 Walker erred in naming the opposing pickets as members of the 6th Maryland. That regiment was not organized until the fall of 1862. I believe only the 1st Maryland were present in Magruder’s army at Yorktown in April 1862.

2 Possibly the 14th Louisiana Infantry which became part of the Louisiana Tiger Brigade.

3 I have searched for any evidence of a French Brigade at Yorktown such as Walker has asserted and found none. “French’s Brigade” of the Army of the Potomac was present near Yorktown and perhaps there was a misunderstanding or miscommunication that resulted in the rumor.

4 William B. Adams served as the Mayor of Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, from January 13, 1854, to roughly 1856. Running as an Independent, he succeeded Robert W. Park and preceded Herman Jeremiah DeHaven in governing the city, which was later annexed by Pittsburgh. I could find no evidence that Adams joined the Confederacy.