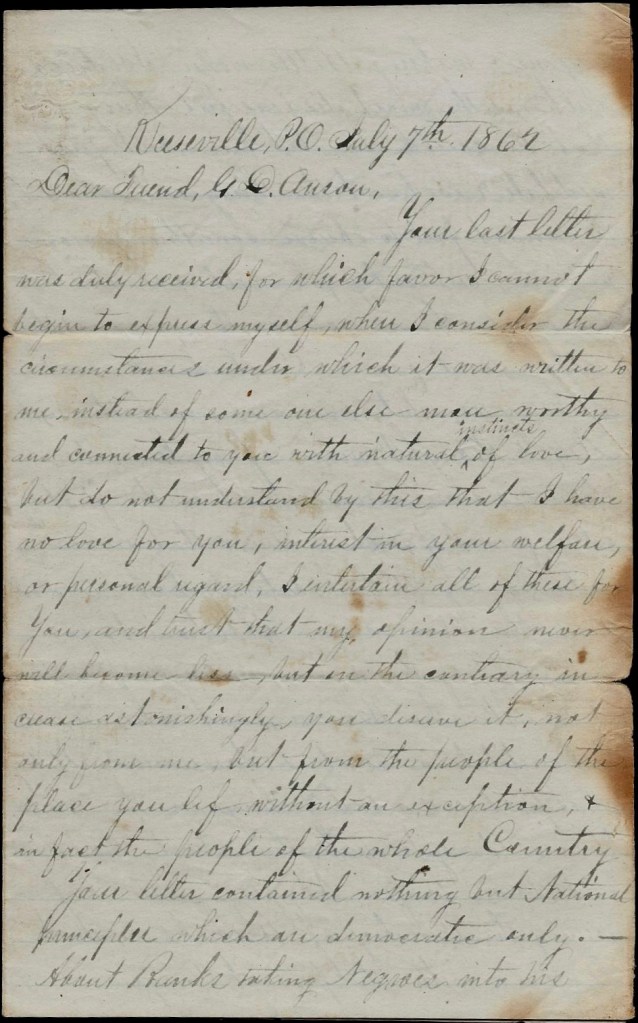

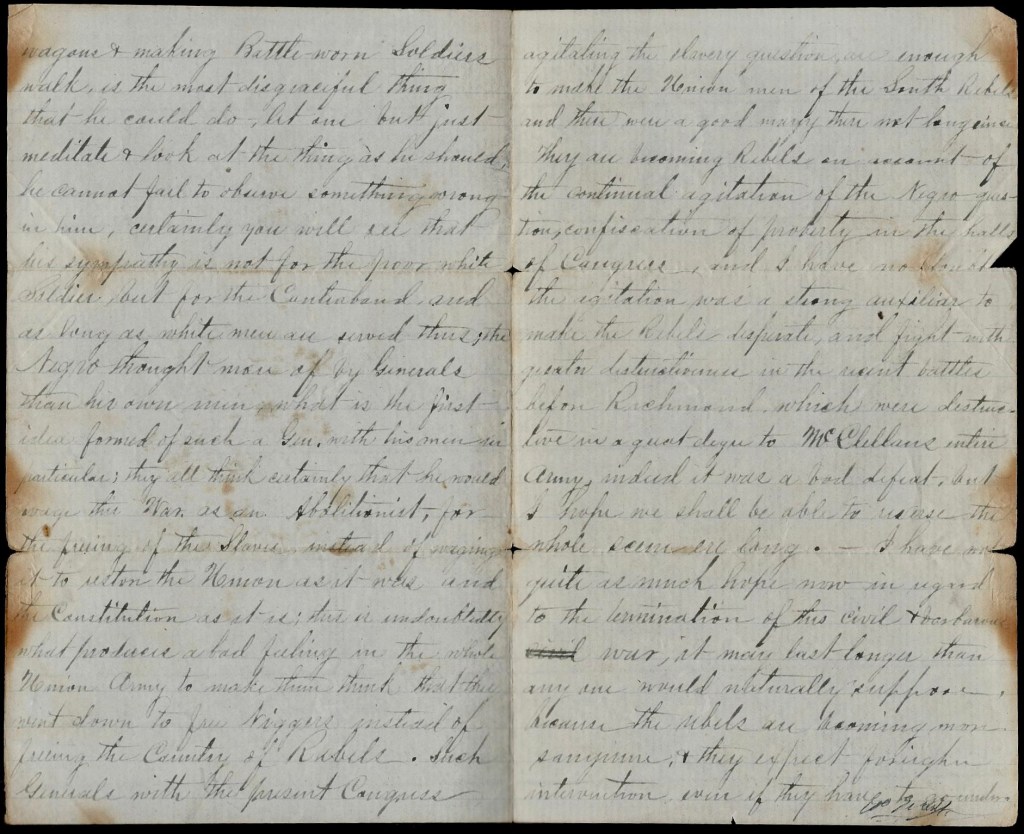

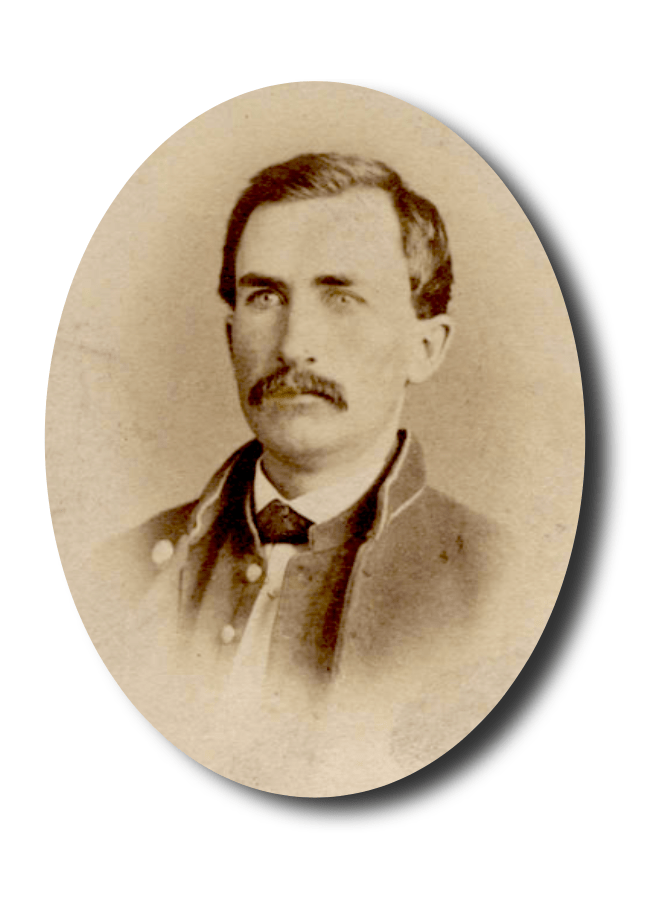

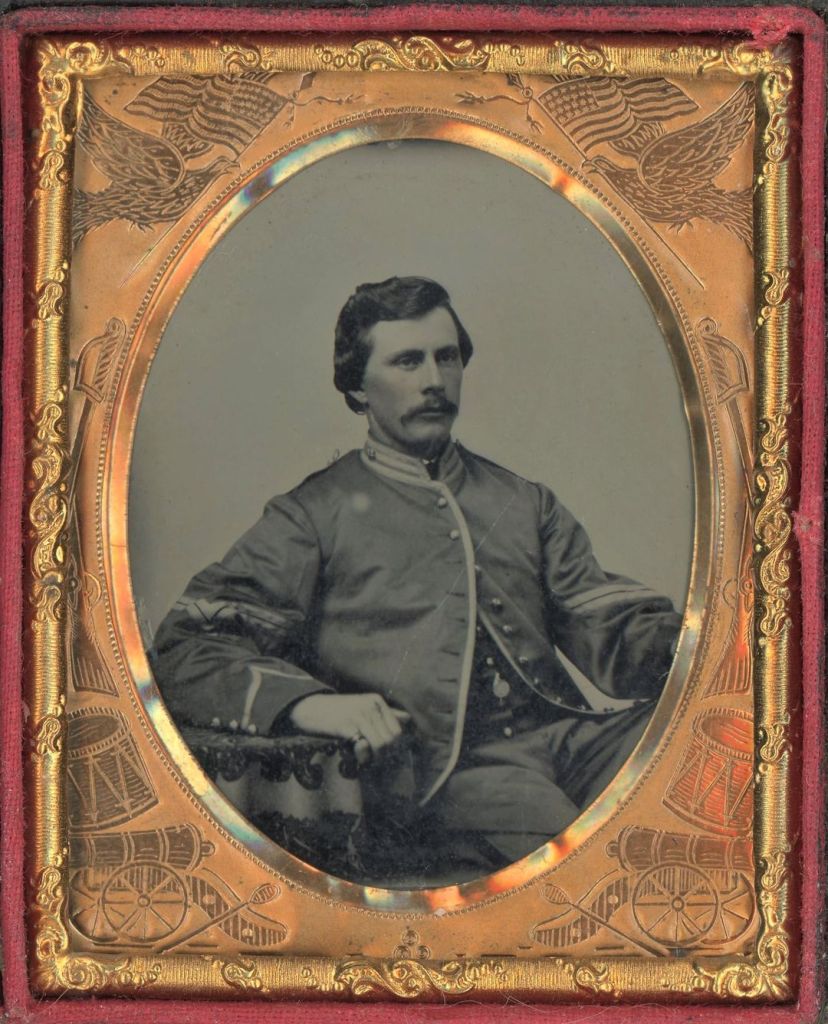

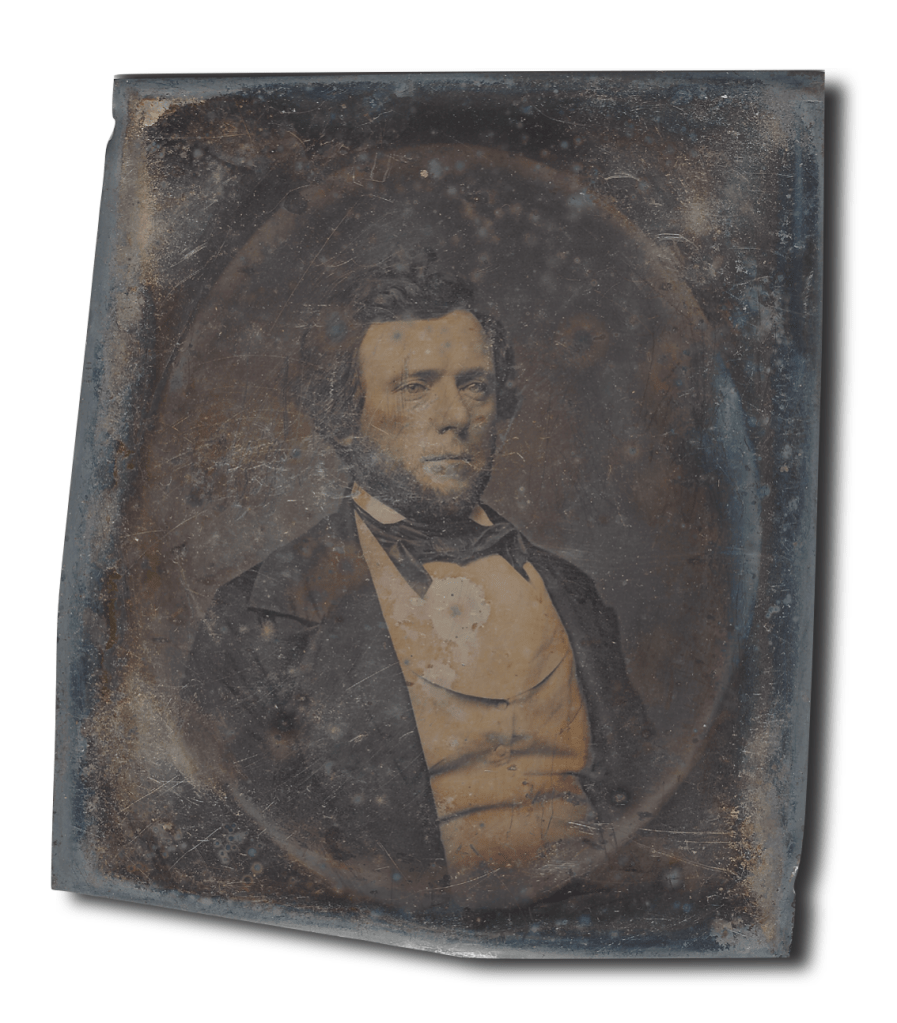

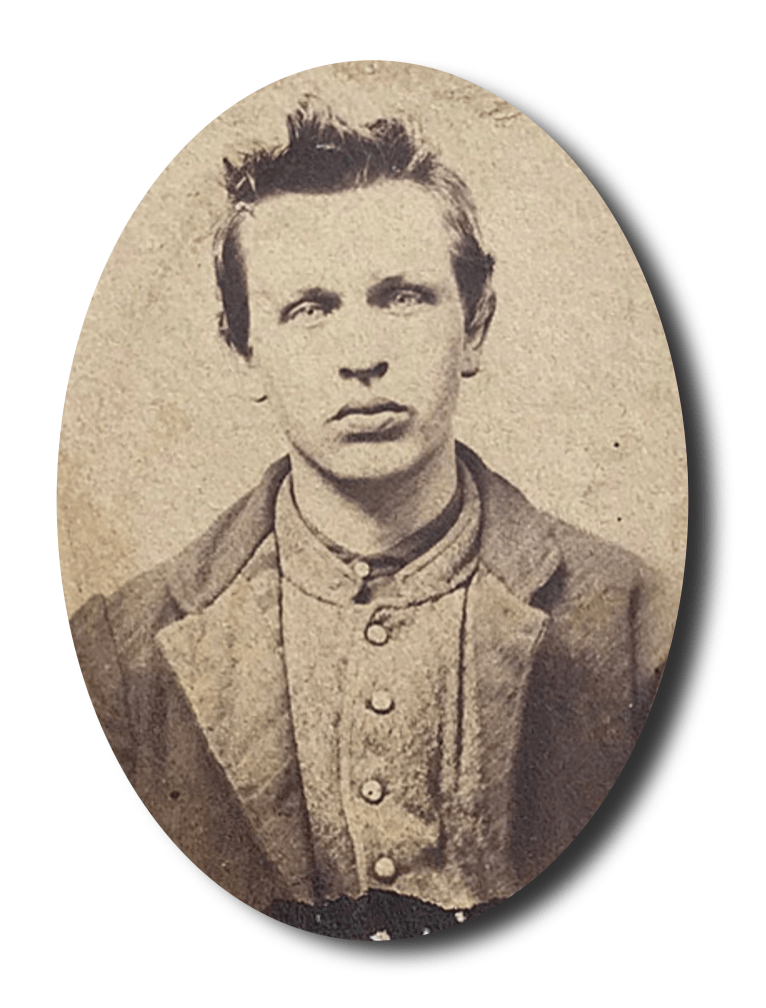

This letter was written by 57 year-old John T. Pool of Terre Haute (1806-Aft1875) who was identified as a “Temperance Lecturer” and enumerated in the 1860 US Census with his much younger wife Nancy D. Castro (b. 1819) and five children.

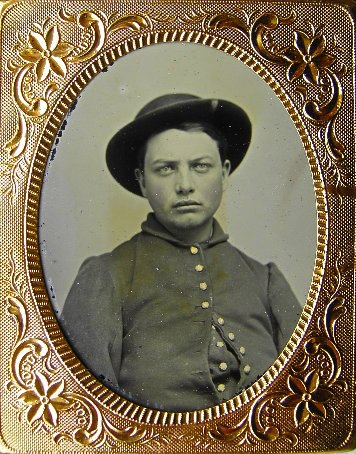

In November 1862, John enlisted as a nurse in Co. G, 6th Indiana Cavalry. Less than a year later he was hospitalized at Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, suffering from rheumatism and partial deafness which enabled him to be discharged from the regiment and transferred to the 2nd Battalion Veteran Reserve Corps. Later in the war he reenlisted in the 71st Indiana Volunteers but then was transferred to the Reserve Corps again. Several years after the war, John was admitted to a Home for Disabled Soldiers at Dayton, Ohio, in June 1872 and discharged on his request in February 1875.

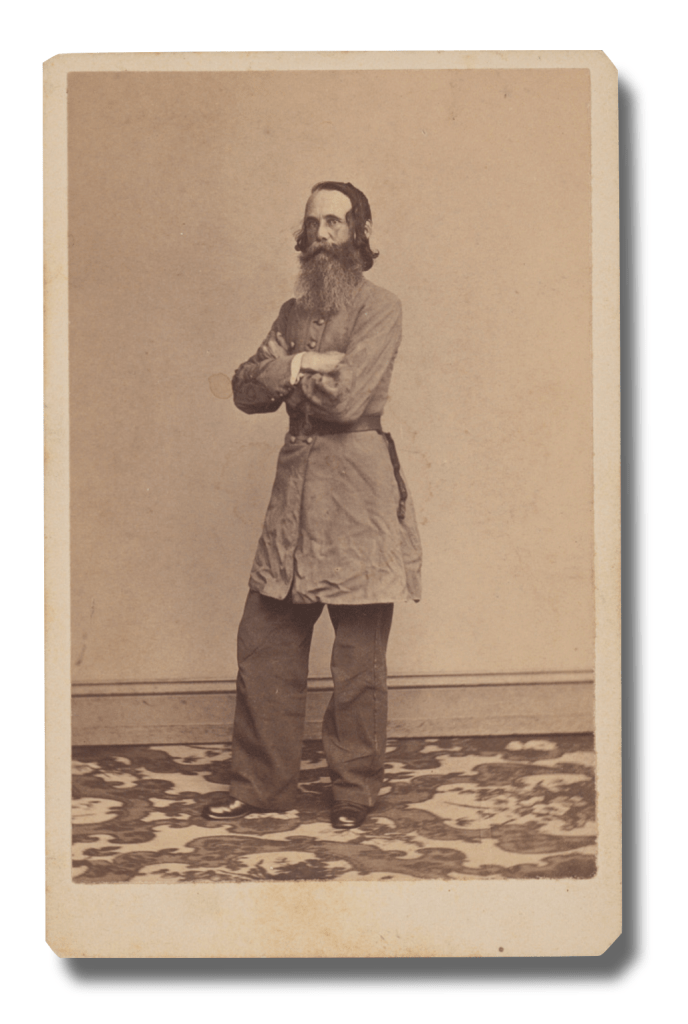

John wrote the letter to his friend Joseph O. Jones (1814-1899) of Terre Haute. Joseph was married to Persis A. Holmes (1820-1908). He was a merchant, volunteer fireman, town clerk, and post master under four different presidents who stood firm as a temperance Democrat. During the Civil War, Joseph served in the “Silver Grays” — a home guard unit whose members were all in their fifties and sixties.

John’s letter speaks of the 2 December 1863 raid on Mt. Sterling by Capt. Peter M. Everett (1839-1900), a native of Mt. Sterling, who resided in Texas just before the war and led Confederate raids in Kentucky. His father was a former governor of Kentucky.

Mt. Sterling served as base for the Union Army operating in the Eastern Kentucky mountain counties, as well as a supply depot. Between October 1863 and May 1864, the US military forces, consisting of troops belonging to the 21st MA Infantry and troops under Asst. Quartermaster J. M. Mattingly, 37th KY Infantry, took possession of and occupied a two-story brick house, a frame building, log house and shed, all situated on Main Street, the property of John Lindsey & Son, manufacturers of furniture and coffins. The buildings were utilized as an office and depot for QM stores and commissary supplies, and as quarters for the troops. The Ascension Protestant Episcopal Church, a well-constructed and well-finished brick building, as well as the grounds, were also occupied by the military and the church used for “Camping and hospital purposes.” The Montgomery County Courthouse was utilized as headquarters. Mount Sterling served as a point of safety for Union refugees from the mountains of Eastern Kentucky who had been driven from their homes by rebel forces and guerrillas. [Mt. Sterling–An important Military Base During the Civil War]

Everett was able to “skedaddle” from Mt. Sterling and avoid detection by using the Rebel Trace—a trail that he was intimately familiar with and only accessible by foot or horseback. His use of the trail is described in the following article:

In December of 1863, Captain Peter Everett CSA used the trail to escape Yankee pursuers after his raid on Mt. Sterling. The captain left Abingdon, Virginia, with the 1st Battalion Kentucky Cavalry, 10th Kentucky Mounted Rifles, and 7th Confederate Cavalry. The Confederates rode rapidly along the Mt. Sterling-Pound Gap Road, stopping long enough in Salyersville to rout a small Union garrison. Later that night, the Rebel raiders successfully attacked a Union force, much larger than their own, that was garrisoned in Mt. Sterling. The raiders captured a large number of horses and supplies, while destroying a large Union commissary stored in the town. Knowing that the Yankees would be expecting them to return to Virginia by the Mt. Sterling-Pound Gap Road, the young captain allowed some of the men of the 10th Kentucky Mounted Rifles to lead the raiding party back along the Rebel Trace. The majority of the men of this regiment was from the mountains of Eastern Kentucky and knew the trail by heart. Upon arriving in Whitesburg, the captain left the 10th Kentucky there to check on their families and continued with the remainder of the raiding party back through Pound Gap. [The Rebel Trace: The Forgotten Mountain Road by Richard G. Brown, et al.]

See also—1862: John T. Pool to Joseph O. Jones published on Spared & Shared 7 in October 2014.

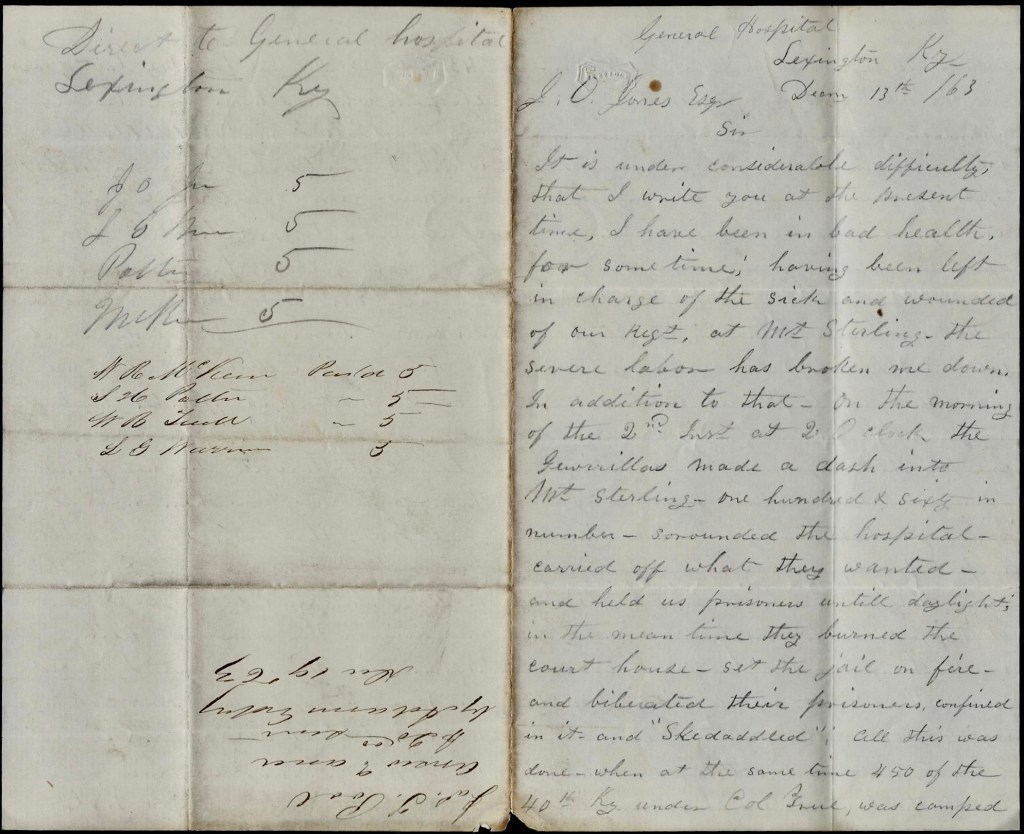

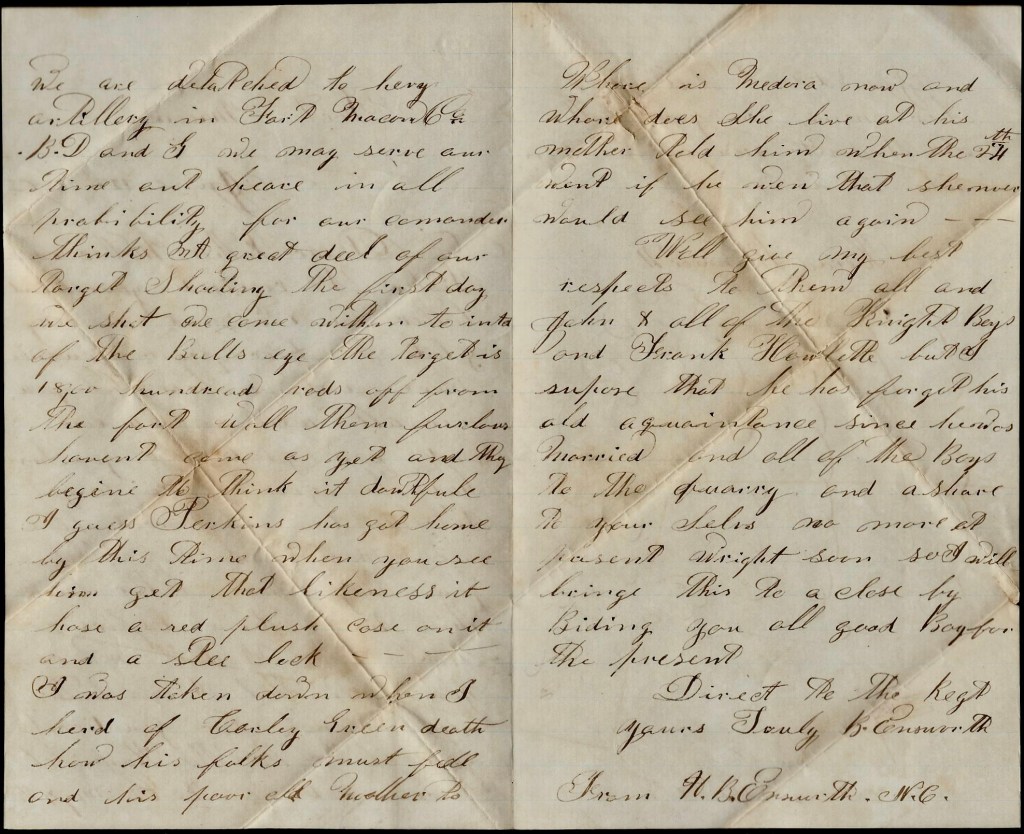

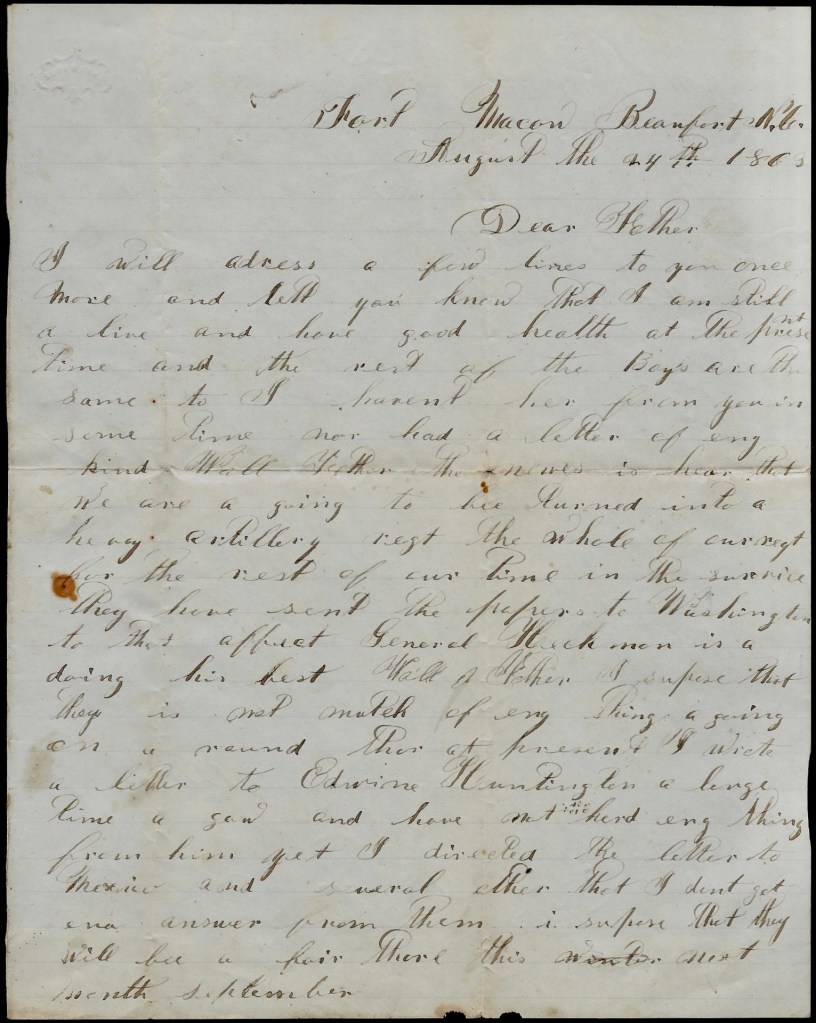

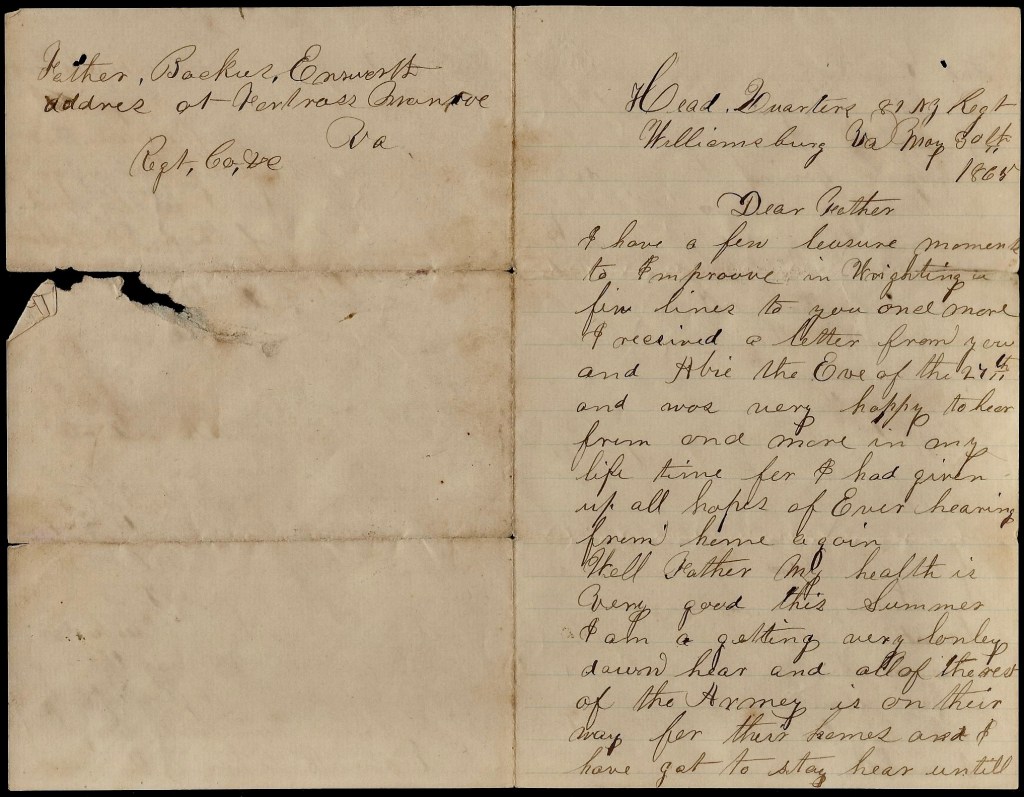

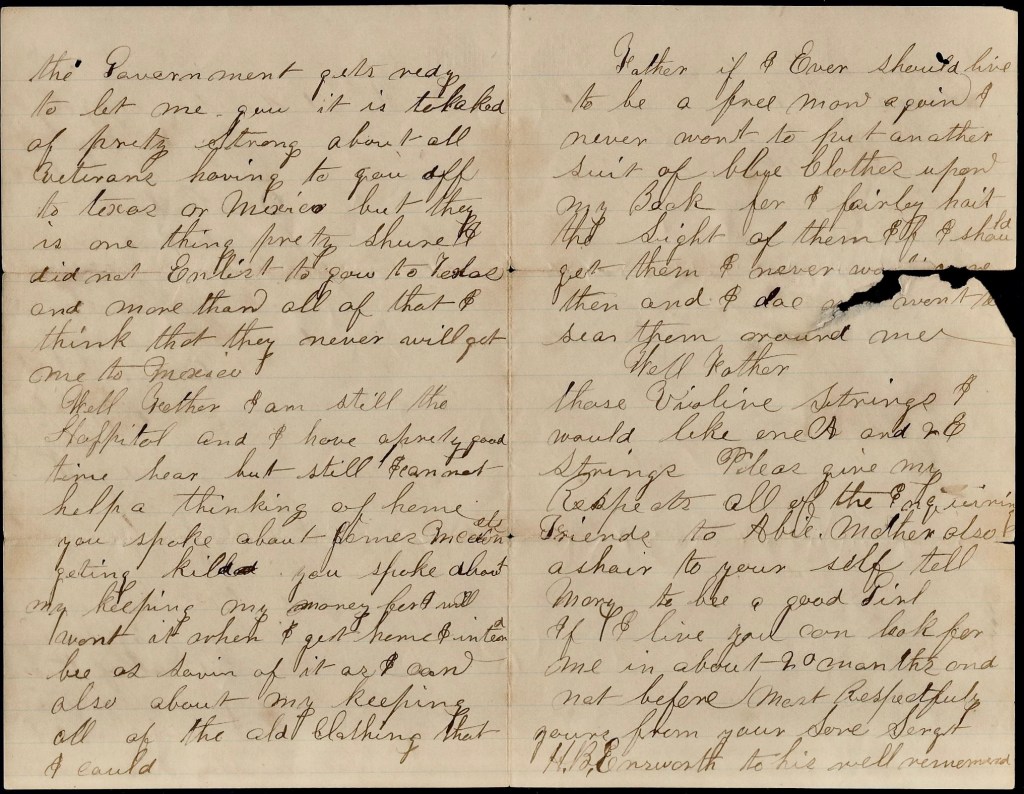

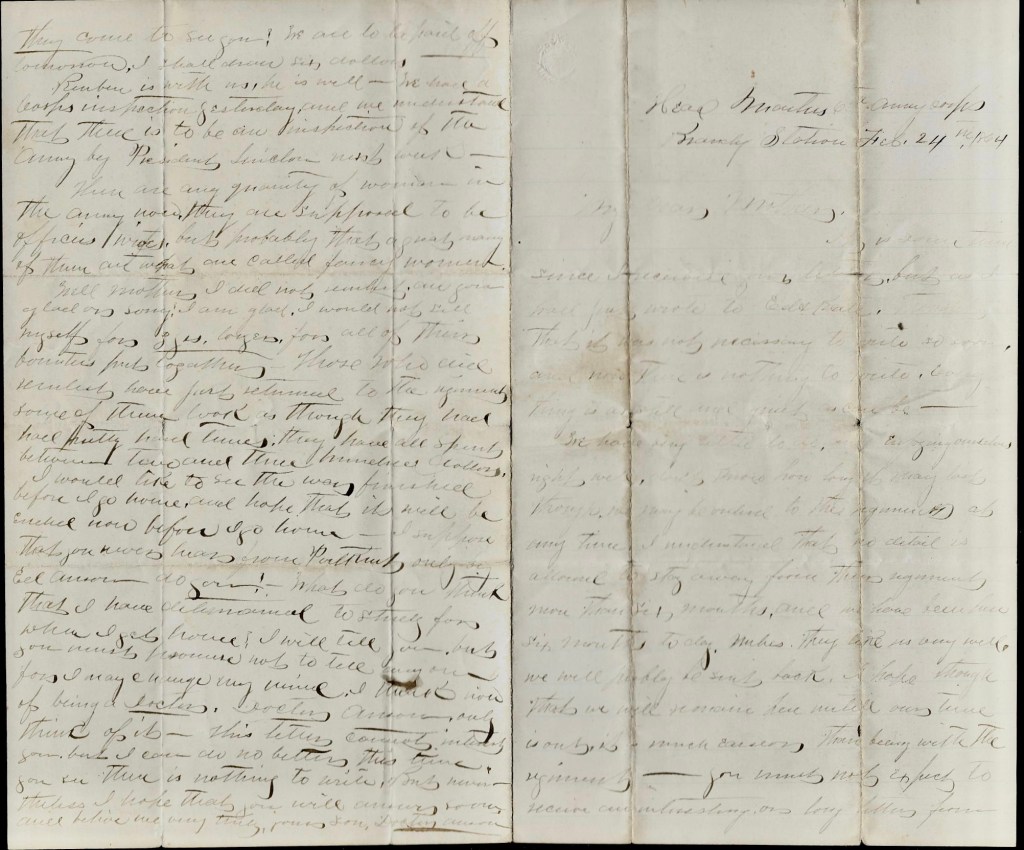

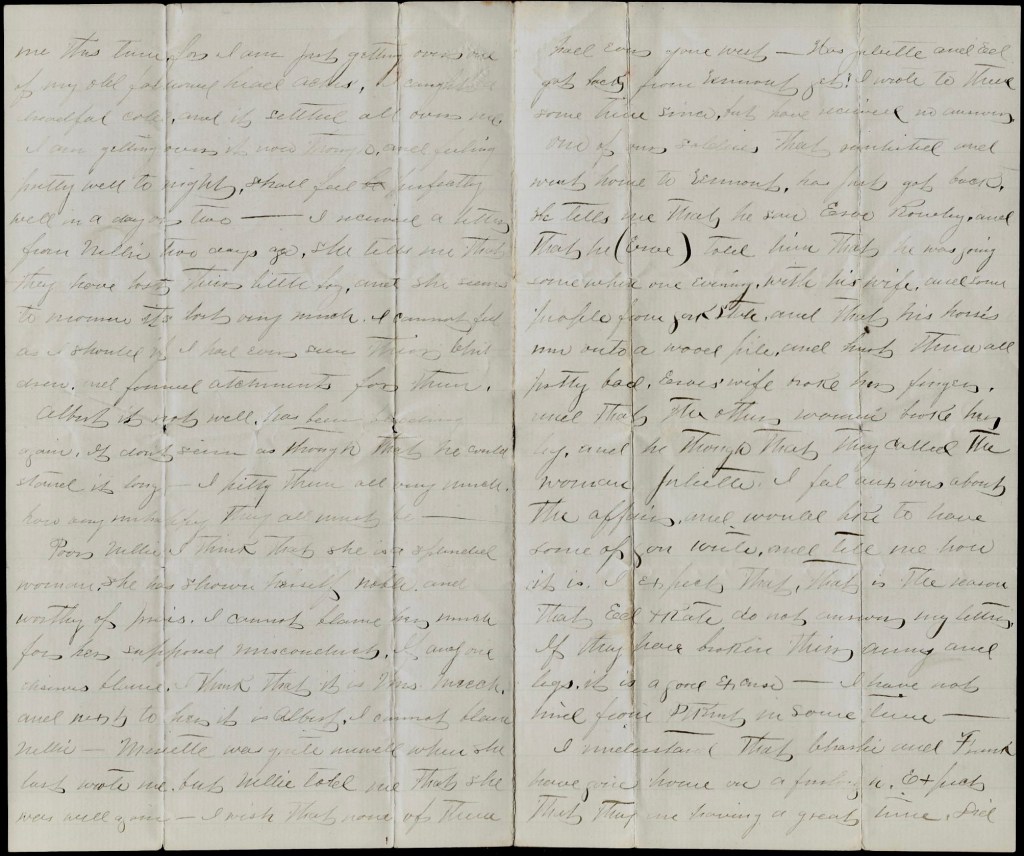

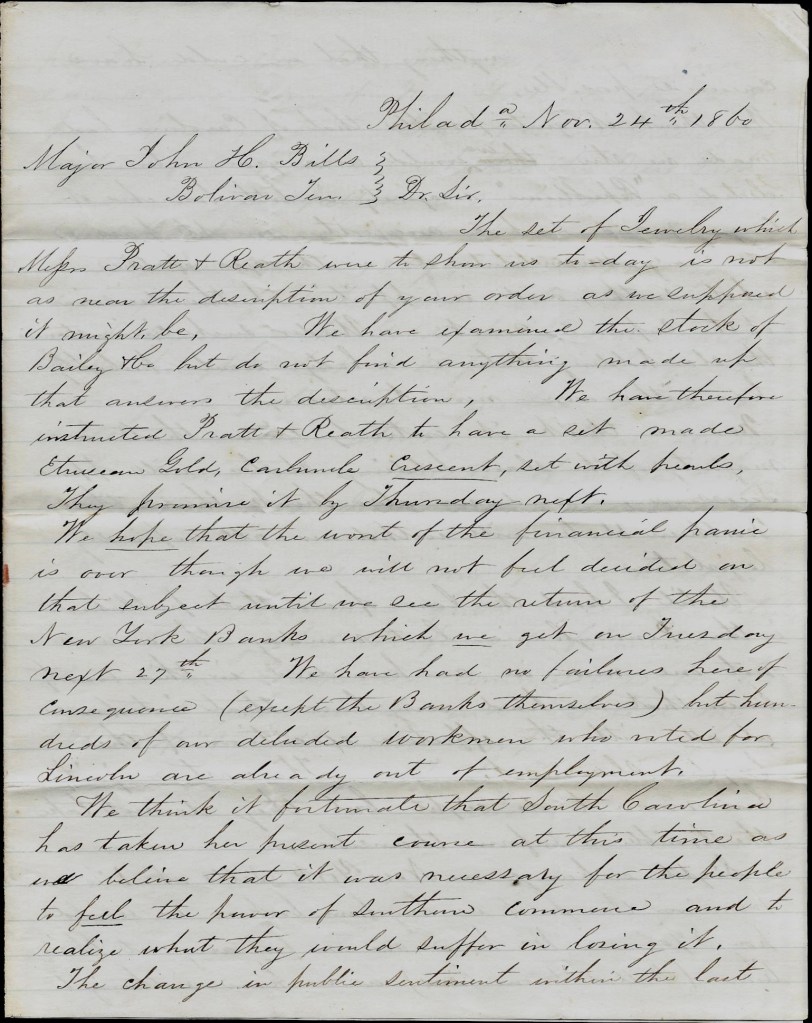

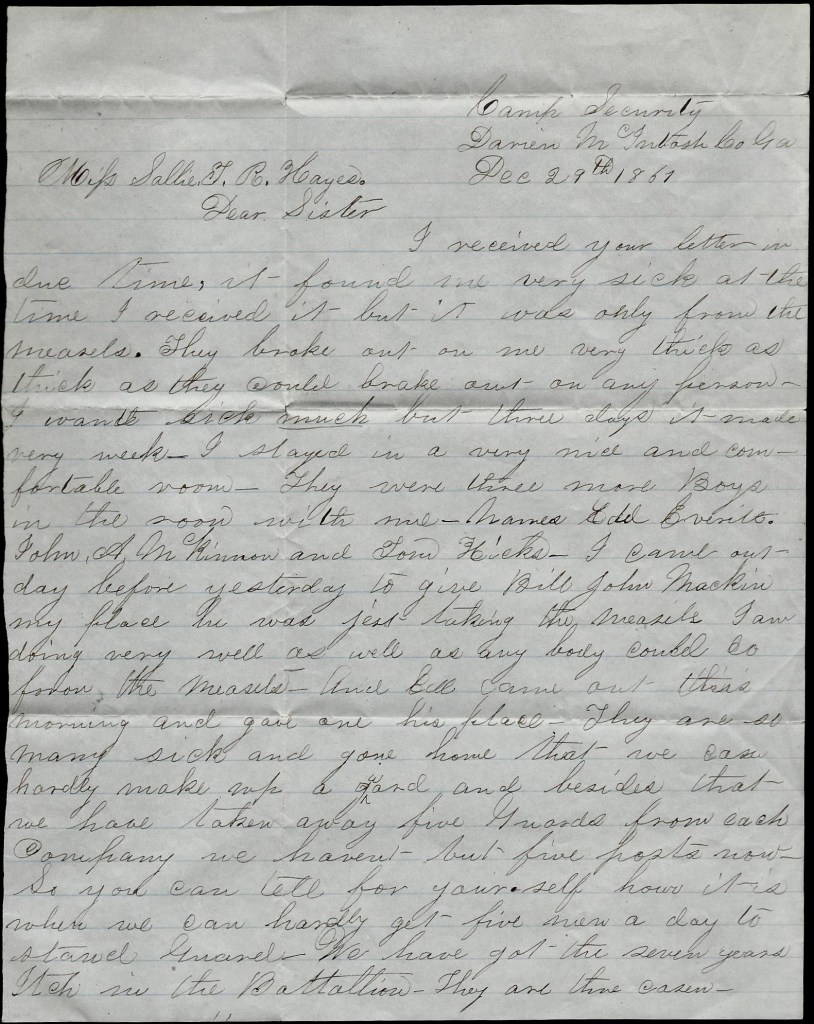

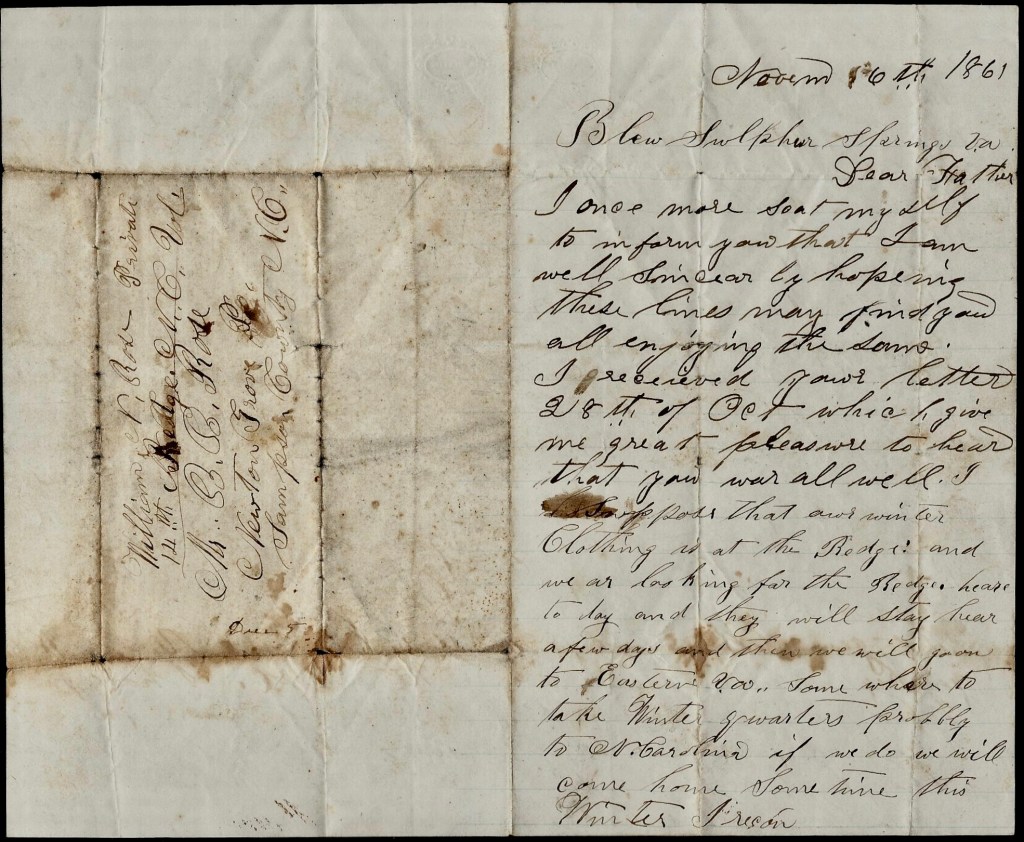

Transcription

General Hospital

Lexington, Kentucky

December 13, 1863

J. O. Jones, Esq.

Sir,

It is under considerable difficulty that I write you at the present time. I have been in bad health for some time having been left in charge of the sick and wounded of our regiment at Mt. Sterling. The severe labor has broken me down. In addition to that, on the morning of the 2nd inst. at 2 o’clock, the guerrillas made a dash into Mt. Sterling—one hundred and sixty in number—surrounded the hospital, carried off what they wanted, and held us prisoners until daylight. In the meantime they burned the court house, set the jail on fire, and liberated their prisoners confined in it, and “skedaddled.” All this was done when at the same time 450 of the 40th Kentucky [Mounted Infantry Regiment] under Col. [Clinton Jones] True was camped within less than two miles of the town and the Colonel had warning of their approach at seven o’clock the evening before.

As soon as we were released, I applied for a discharge for myself and squad from the hospital and after some delay, got it—Col. True positively refusing to allow us the use of the ambulance (although two stood idle in the yard) to convey my two wounded me to Paris. We took the rough road wagons for it and here we are for the purpose of recuperating.

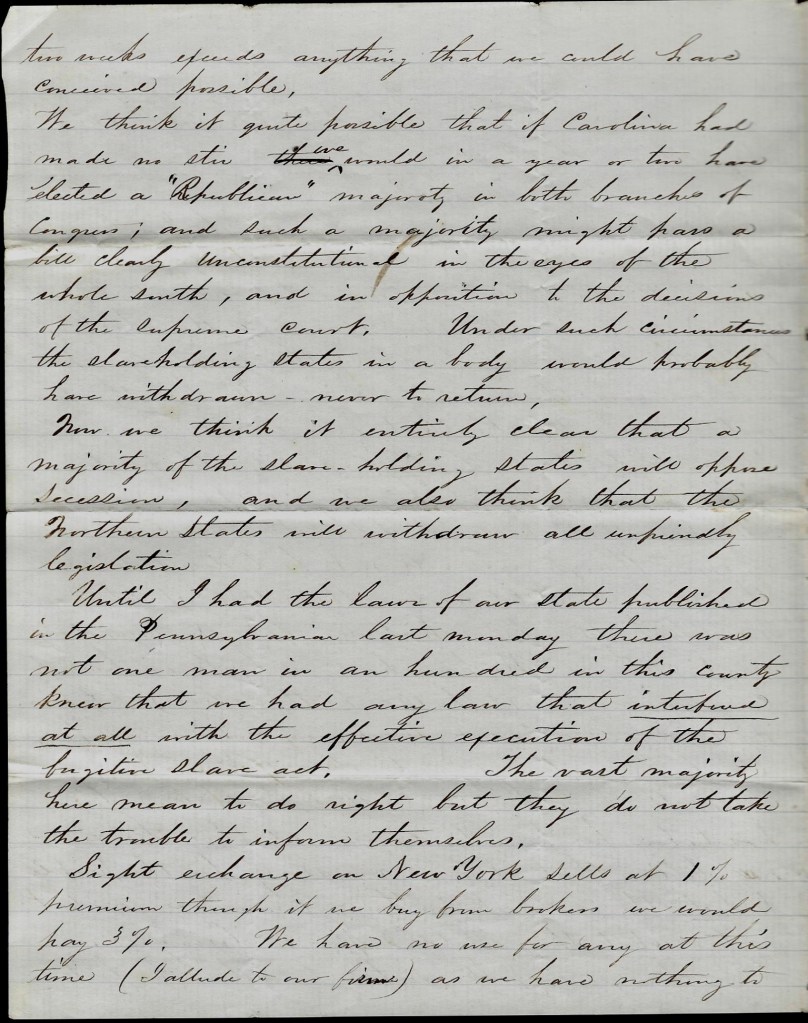

I am in what we call in Terre Haute, a “bad fix.” Not having drawn a dime of pay for six months, my clothes all gone, my descriptive roll no where [and] it is impossible for me to draw money or clothing for two months to come unless I can get my descriptive roll which is one of the uncertainties. I have 78 dollars monthly pay coming to me the last of this month, besides 43 dollars due me for my last year’s clothing which I have not drawn—all of which makes 121 dollars which I should have in my pocket on New Year’s day, were I in a condition to reach it.

If I have got any friends in Terre Haute, now is the time to show hands. I want to borrow of somebody twenty or twenty-five dollars to buy me a coat, hat, and pants. My boots I succeeded in hiding so that the rebel cut-throats did not find them and now have them on—and a good pair they are. If you will please to act as my agent in this matter and send by express, you may rely on the amount being refunded the moment I draw my pay. It may be that I am asking too much but a man in my “fix” has a pretty hard face and that must be my excuse. — John T. Pool

Direct to General Hospital, Lexington, Ky.