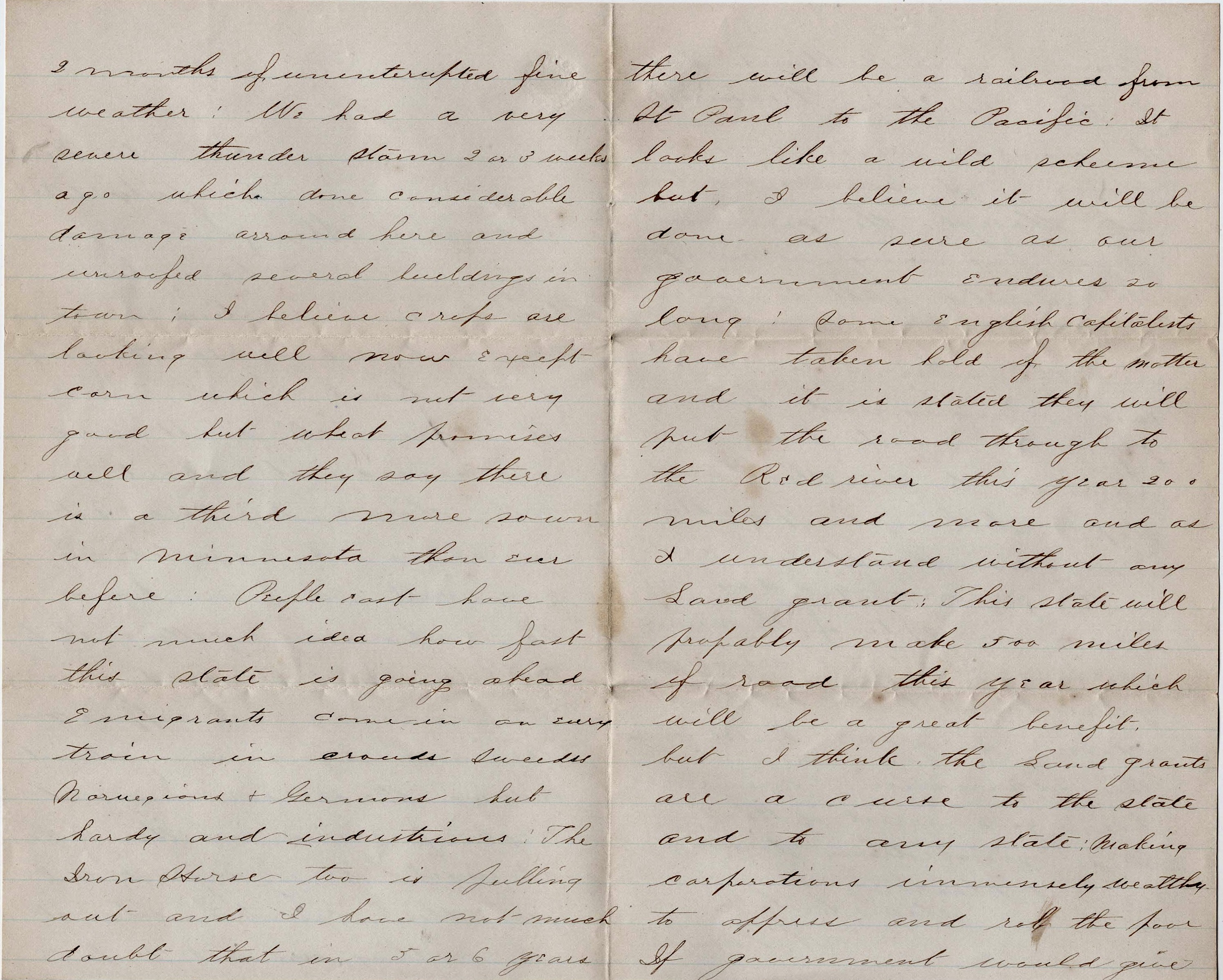

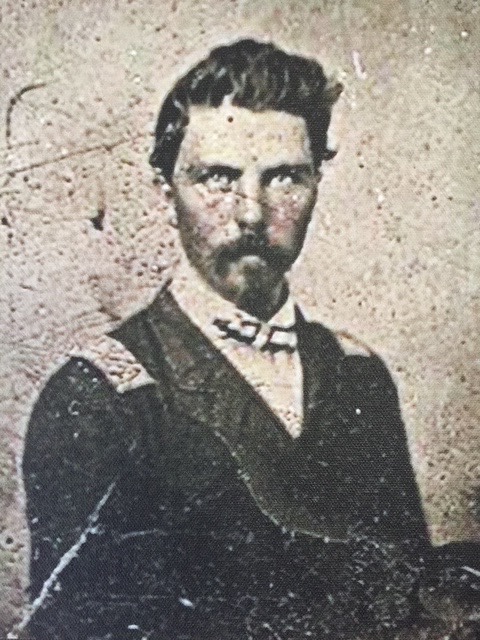

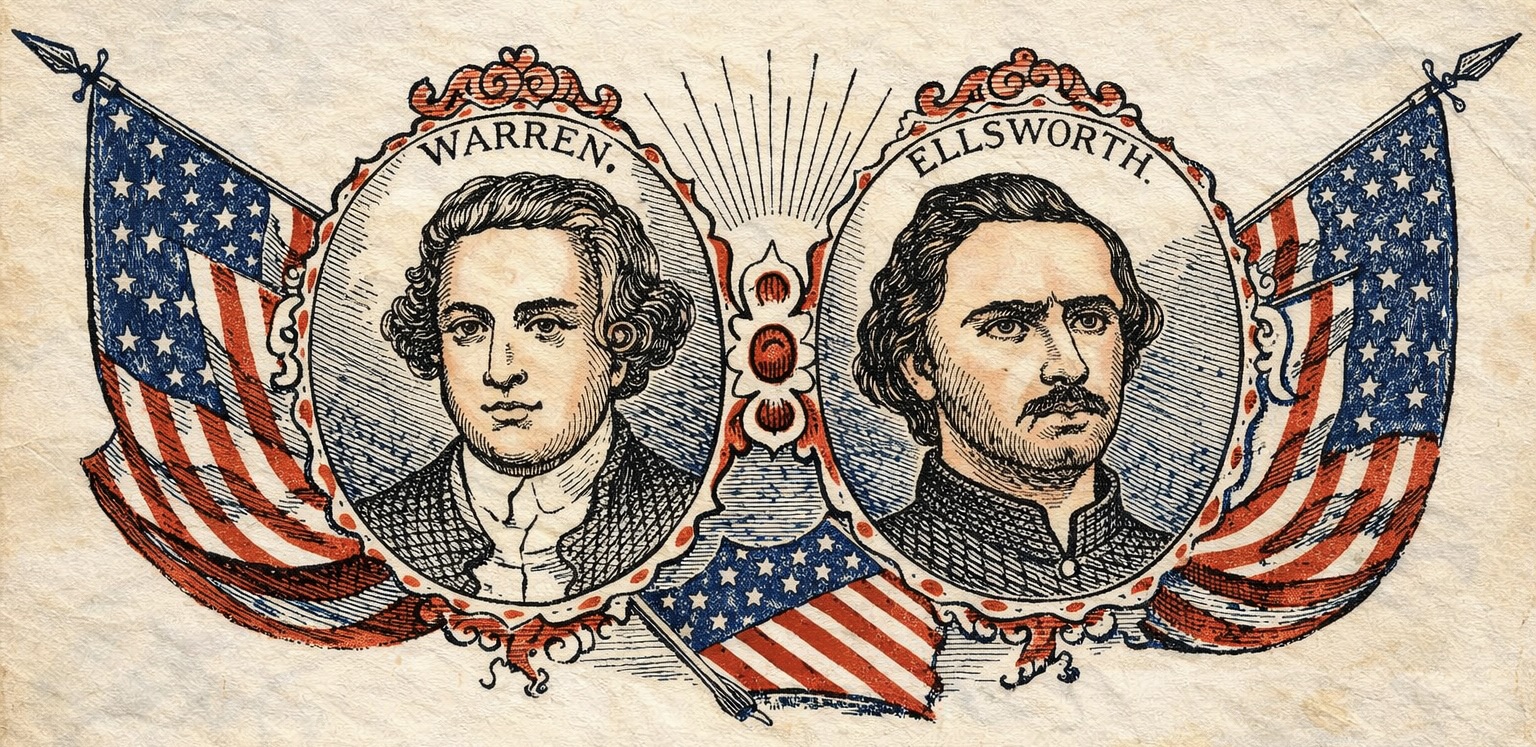

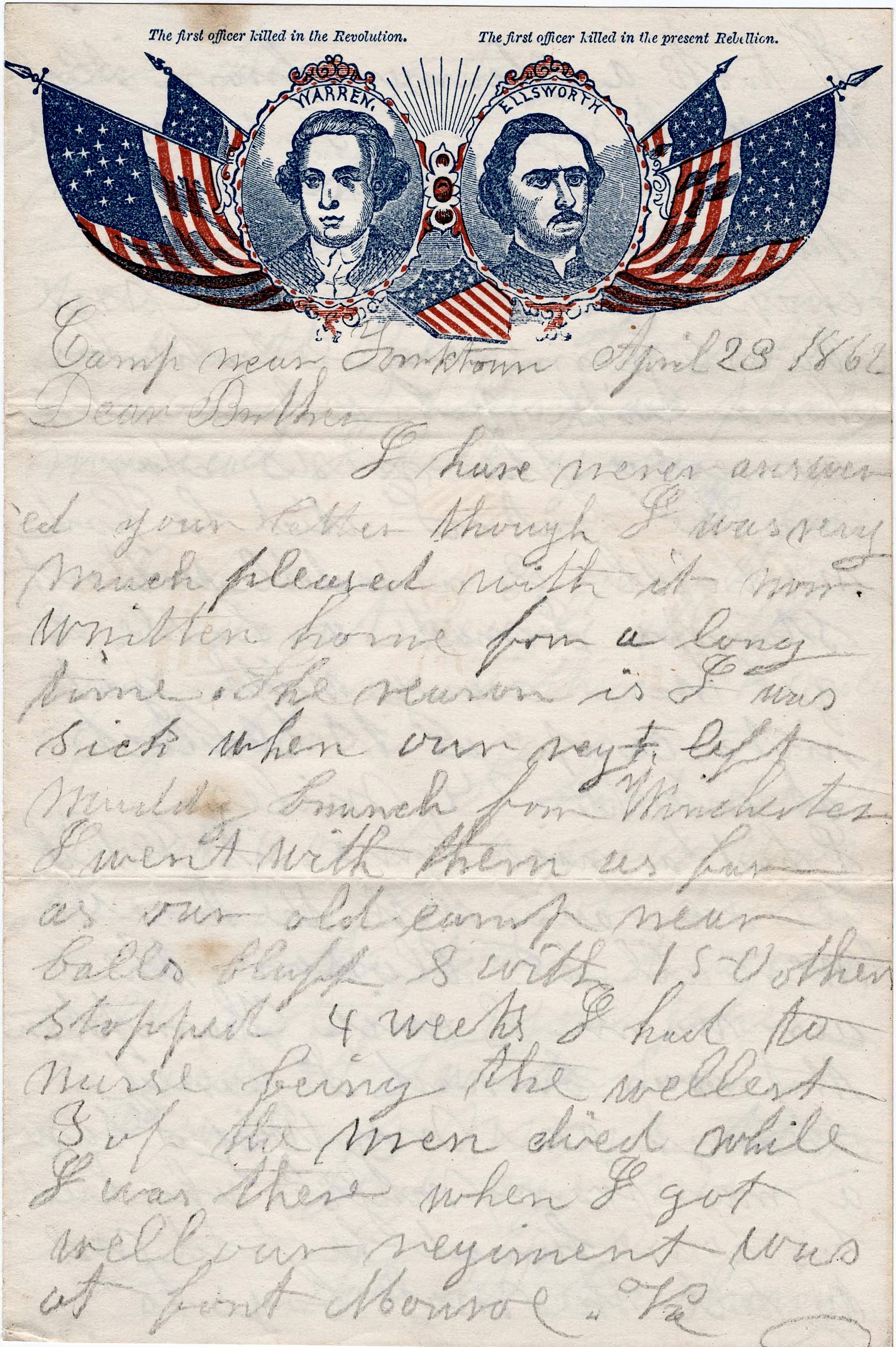

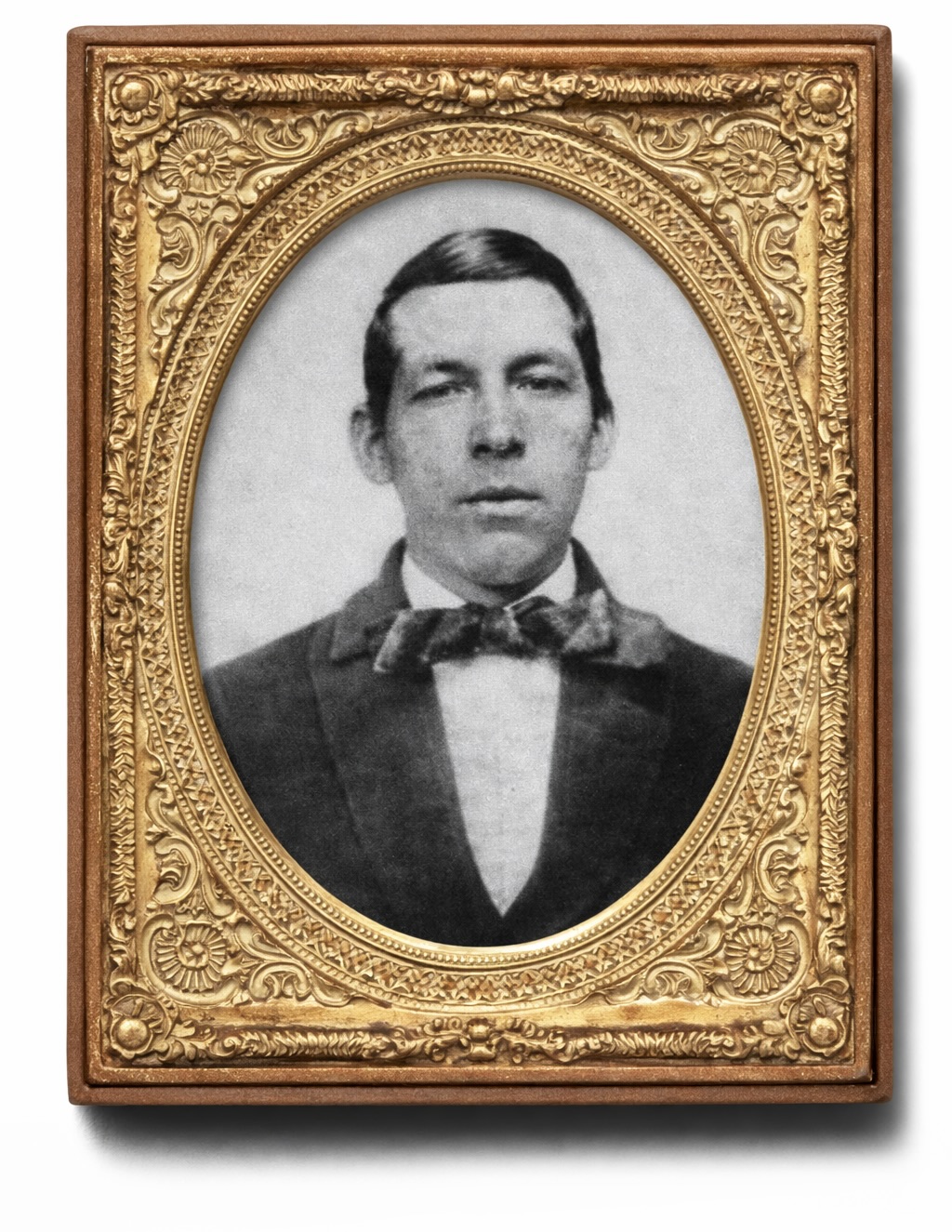

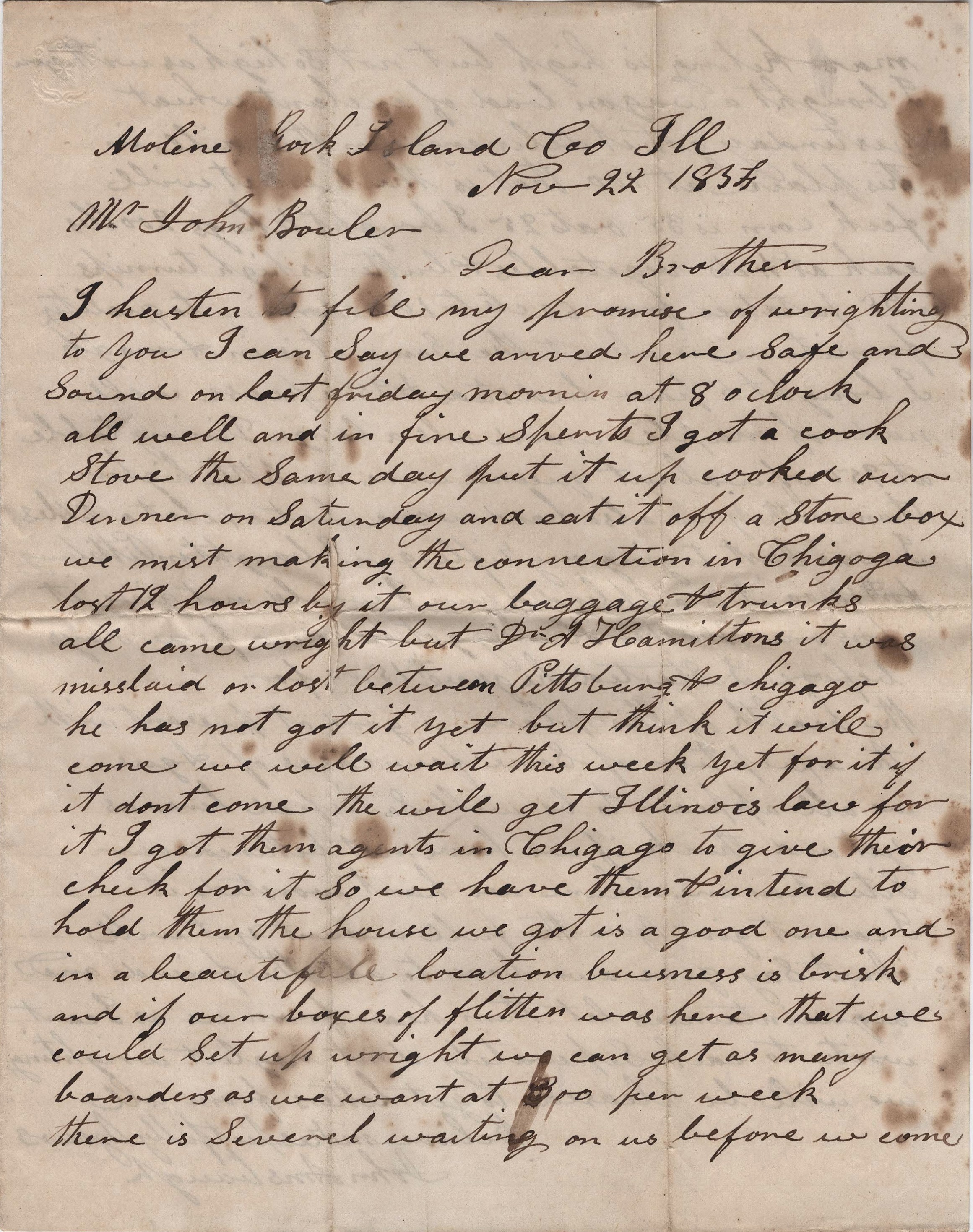

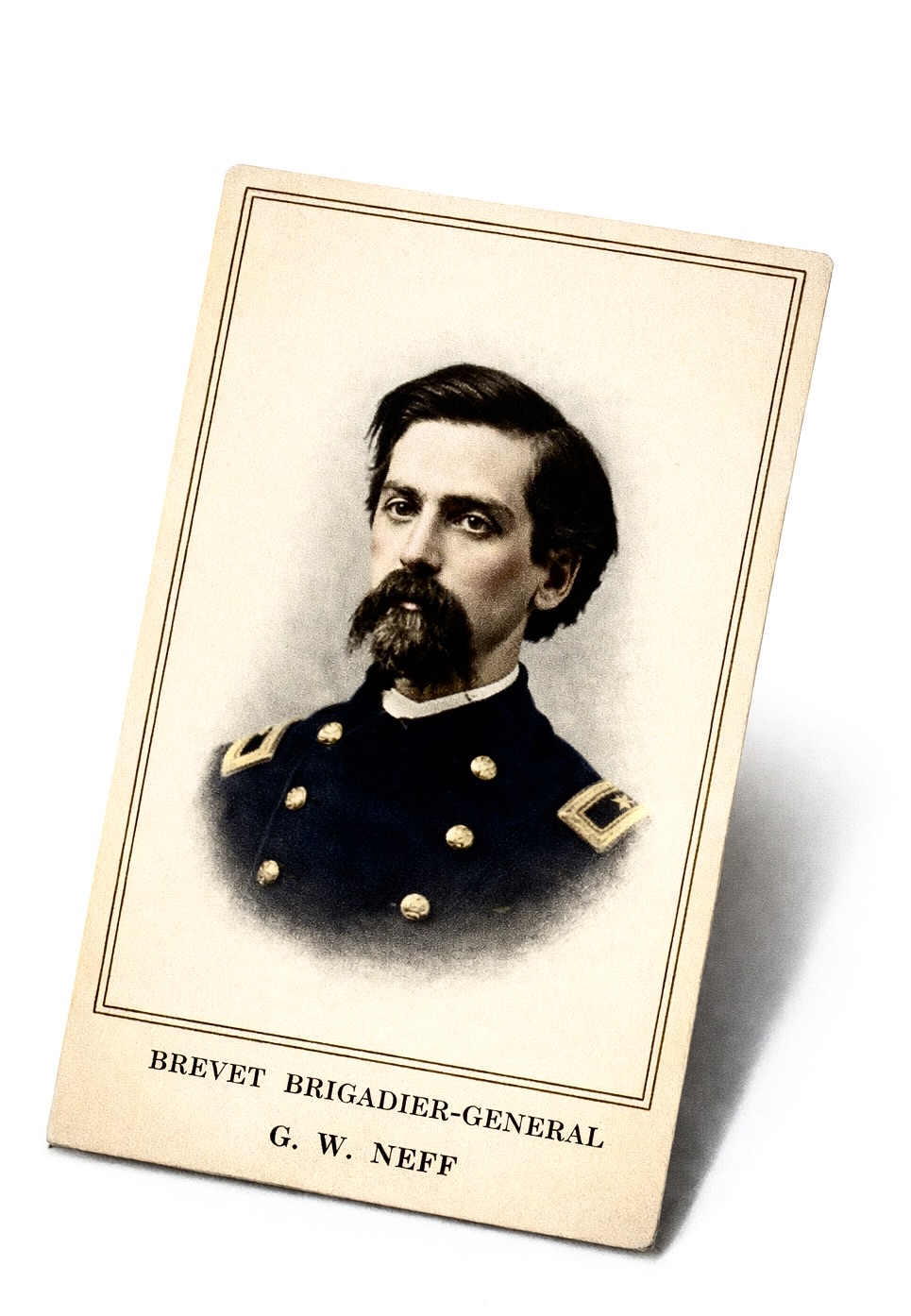

The following letter was written by George Washington Neff (1833-1892), the son of George Washington Neff (1800-1850) and Maria White (1802-1871). It was penned less than a week following the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861.

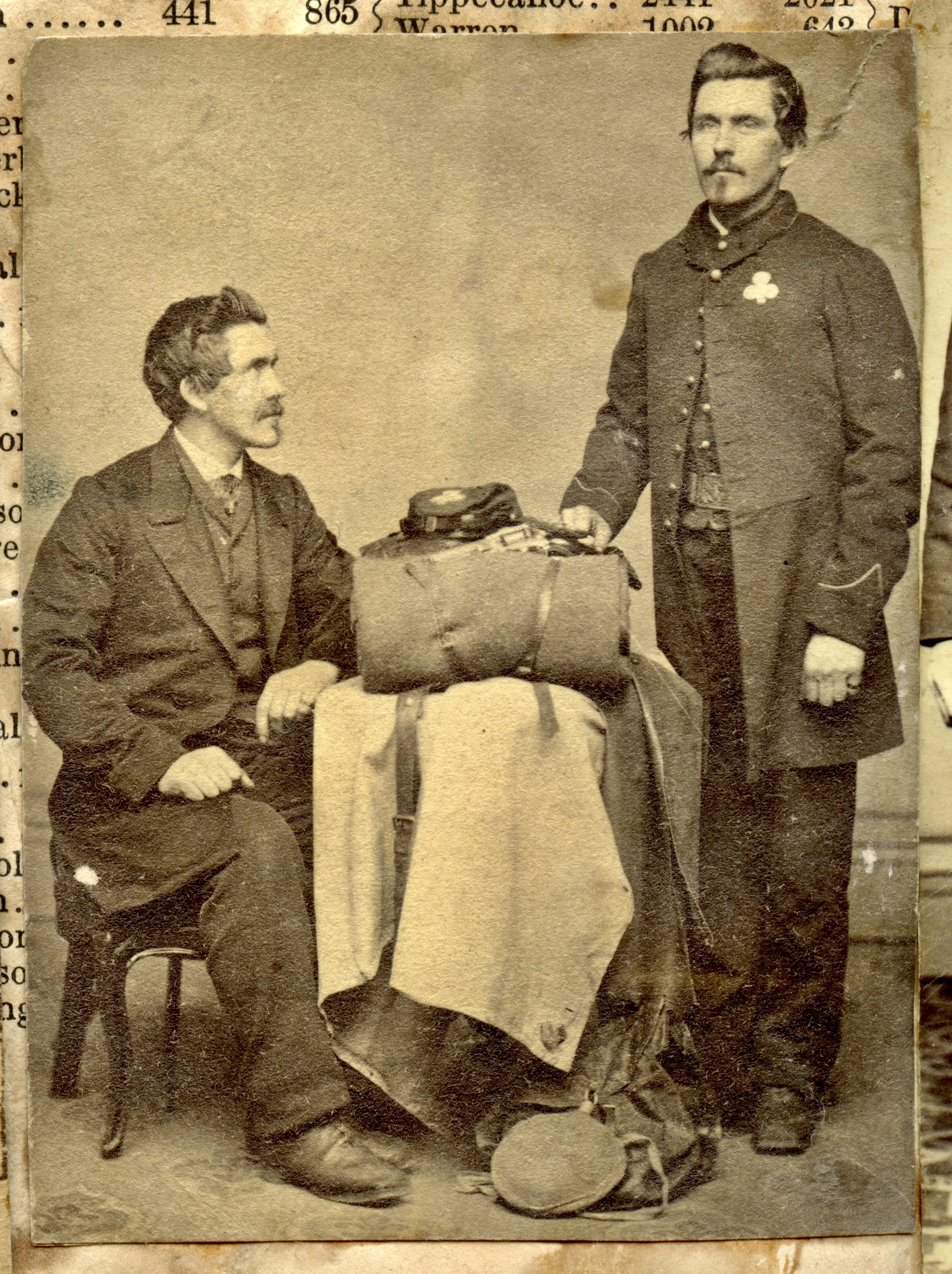

A biographical sketch of the author can be found on Find-A-Grave which reads: “Union Civil War Officer, Brevet Brigadier General. A native of Cincinnati, Ohio, he attended Woodward College and worked as a shoe merchant and an insurance agent.

Before the Civil War, he served with the Rover Guards, a detachment of local militia. In 1861, he was appointed to organize the 2nd Kentucky Infantry, comprised mostly of Ohio soldiers, at Camp Harrison in Hamilton County, Ohio. He led the regiment into western Virginia where he was captured by Confederate forces during a skirmish at Scary Creek on July 17, 1861, and held as a prisoner of war for thirteen months.

After he was paroled, he returned to Cincinnati and commanded Camp Dennison when the camp was threatened by Confederate General John Hunt Morgan’s raid into Ohio. He then served briefly on the staff of Major General Lew Wallace in Cincinnati. He was commissioned as a Colonel in 1863 and assigned to organize the 88th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, also known as the “Governor’s Guard,” at Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio. He was the regiment’s commanding officer during guard duty at the camp’s prison. He received a brevet promotion from Colonel to Brigadier General on March 13, 1865. Bio by: K Guy”

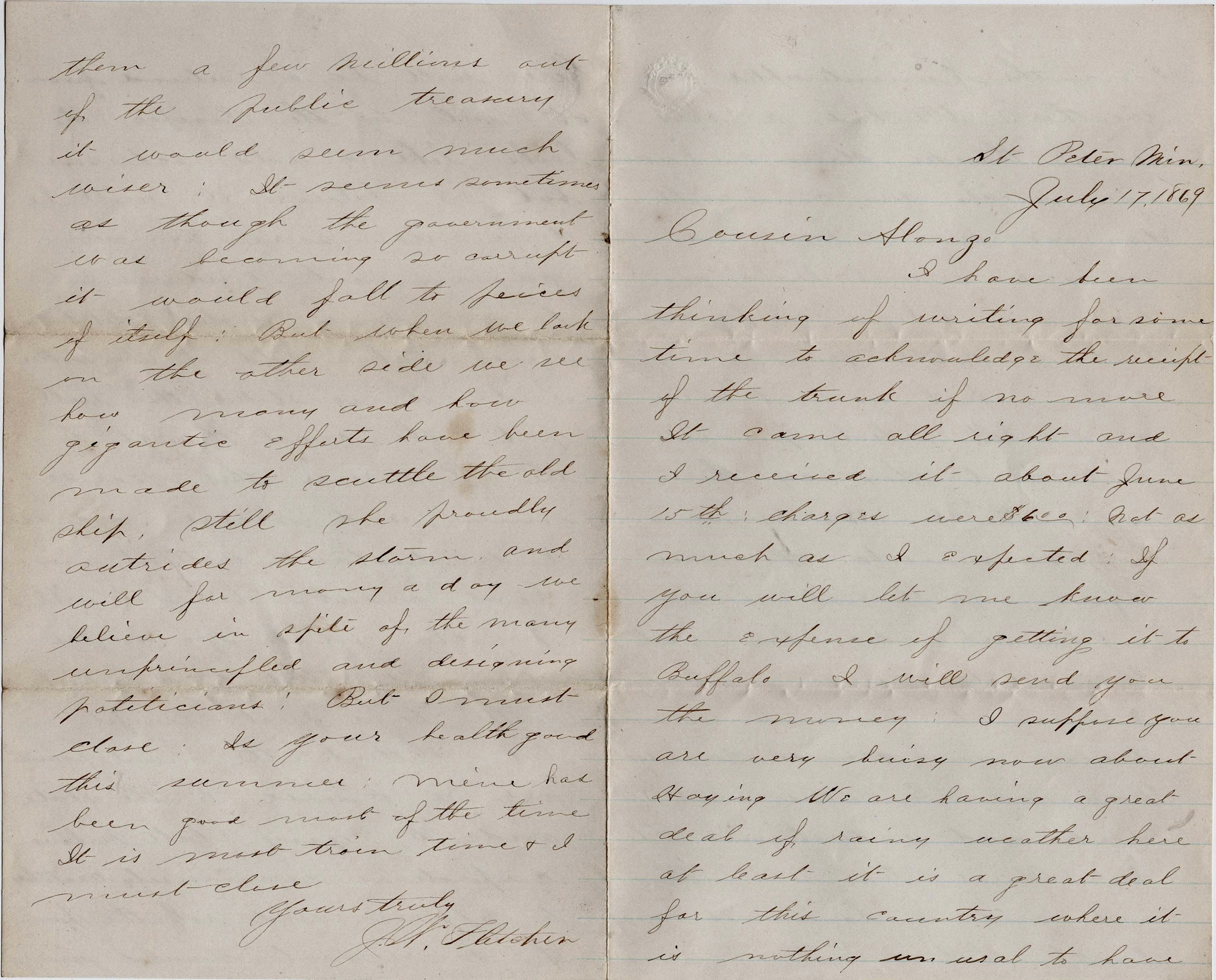

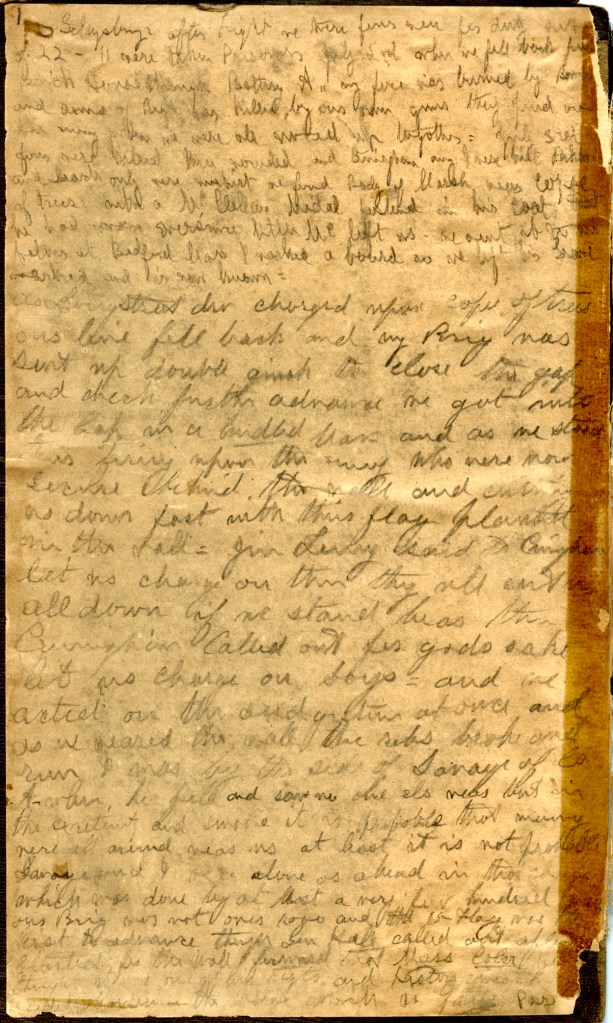

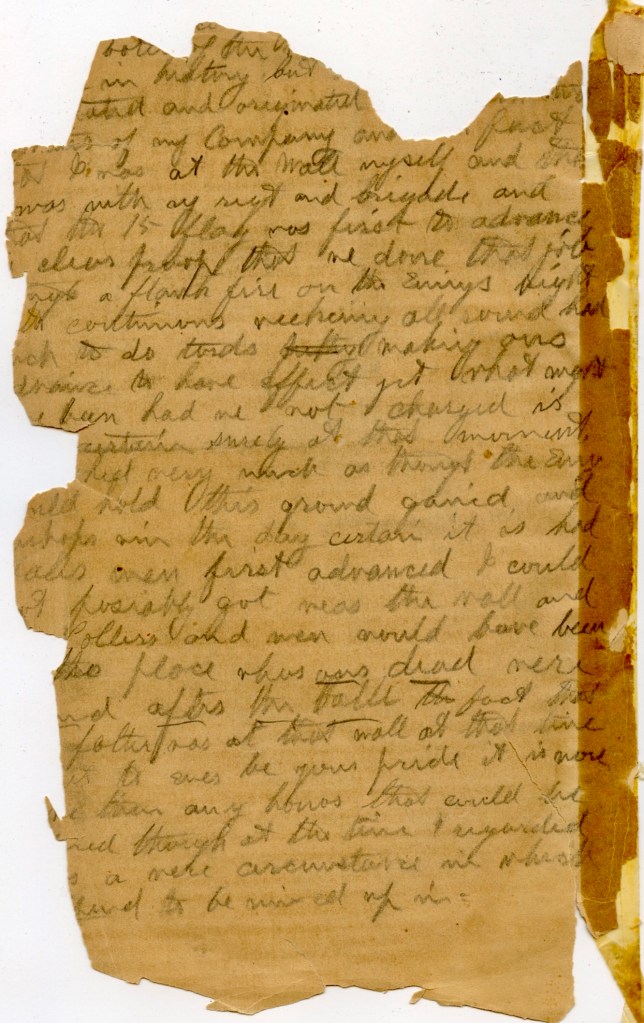

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

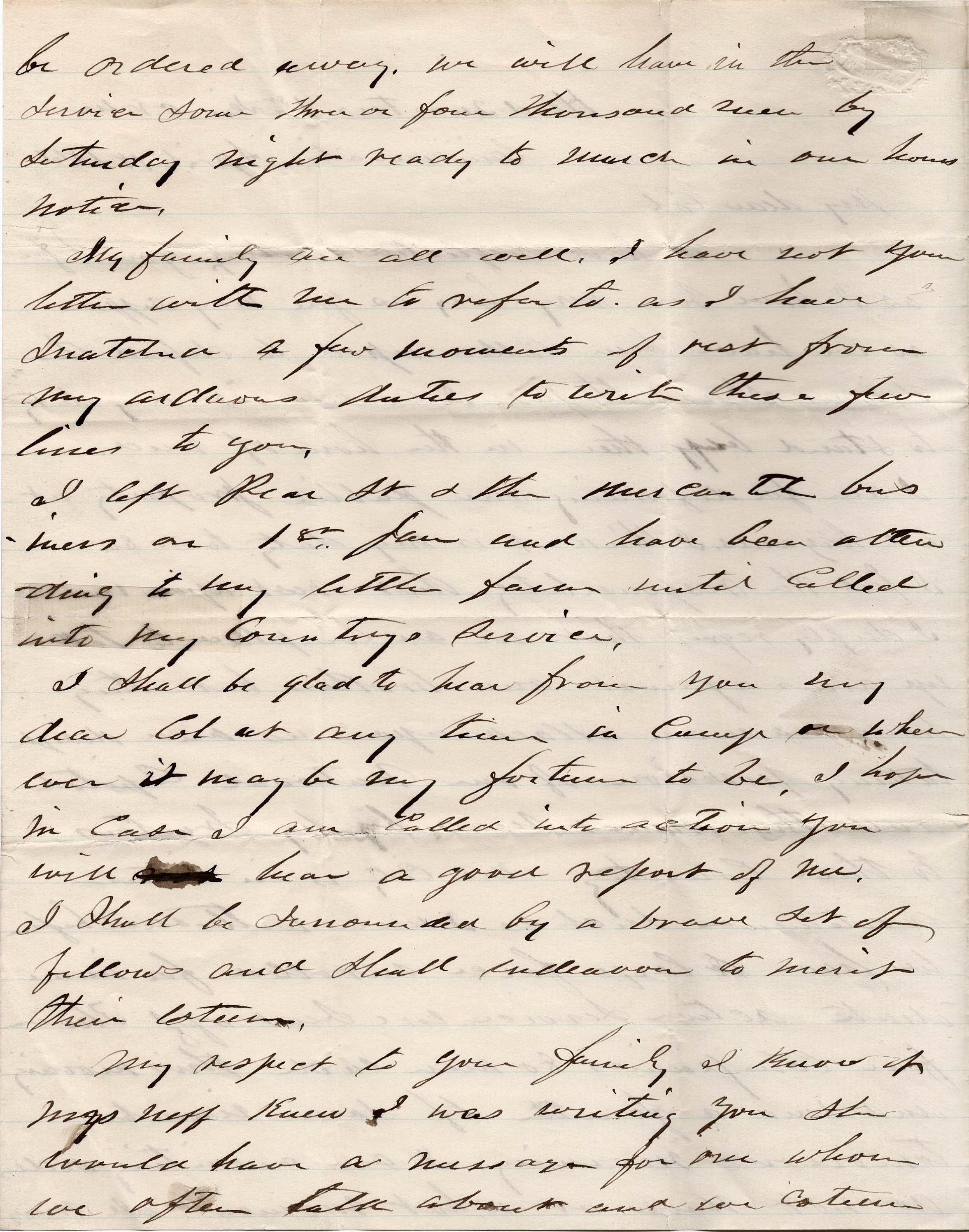

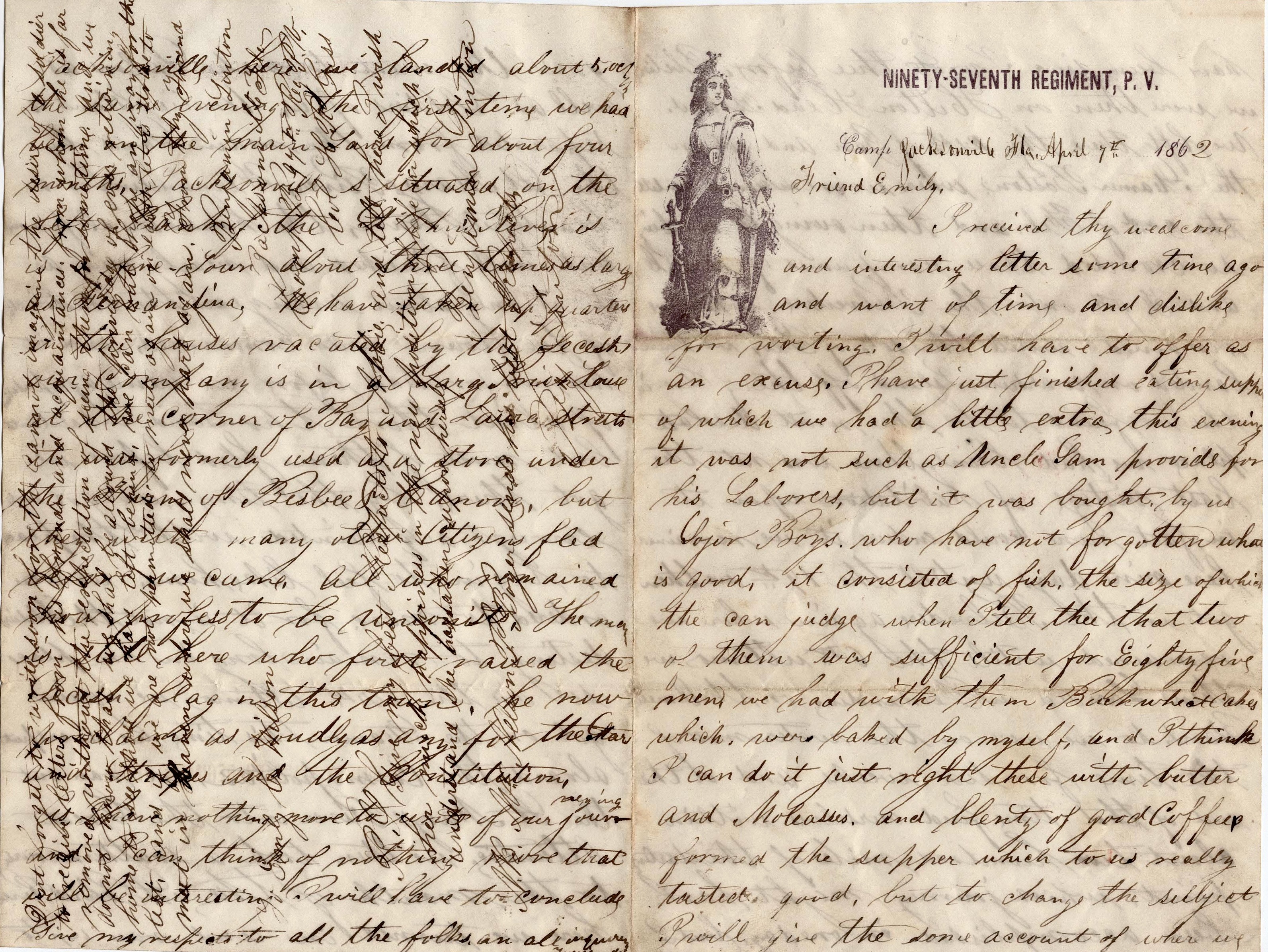

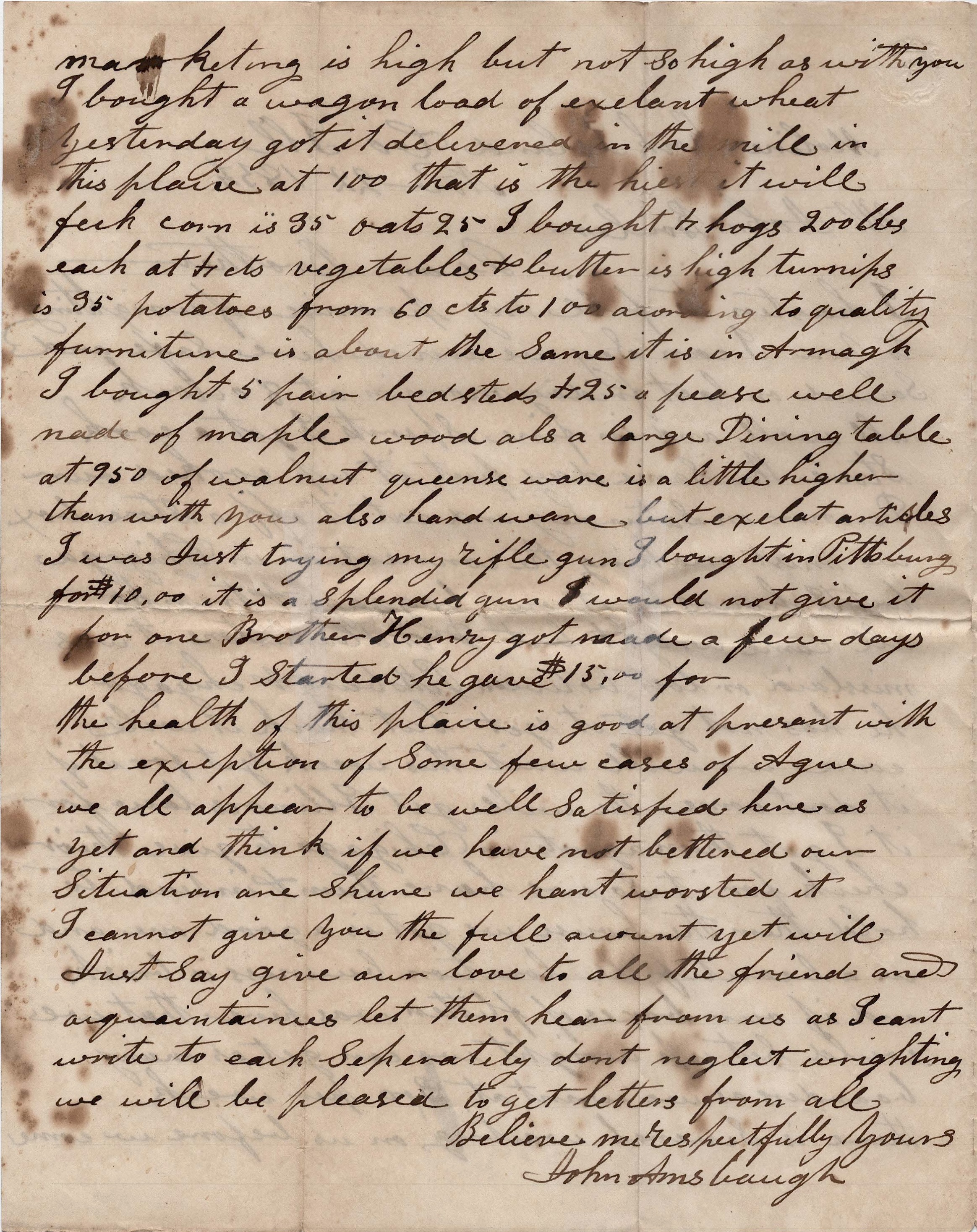

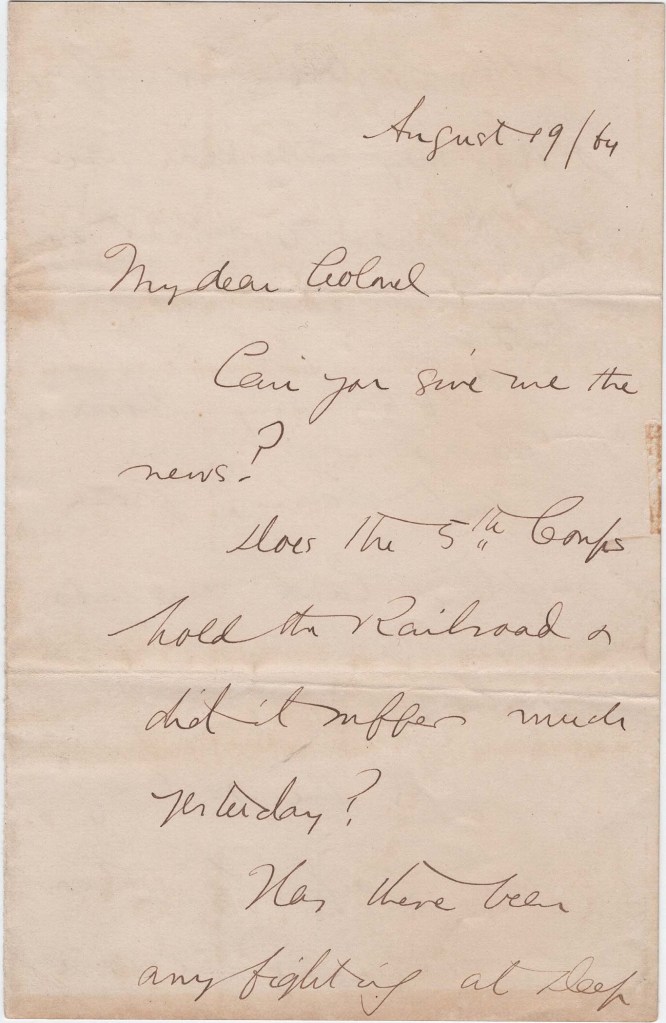

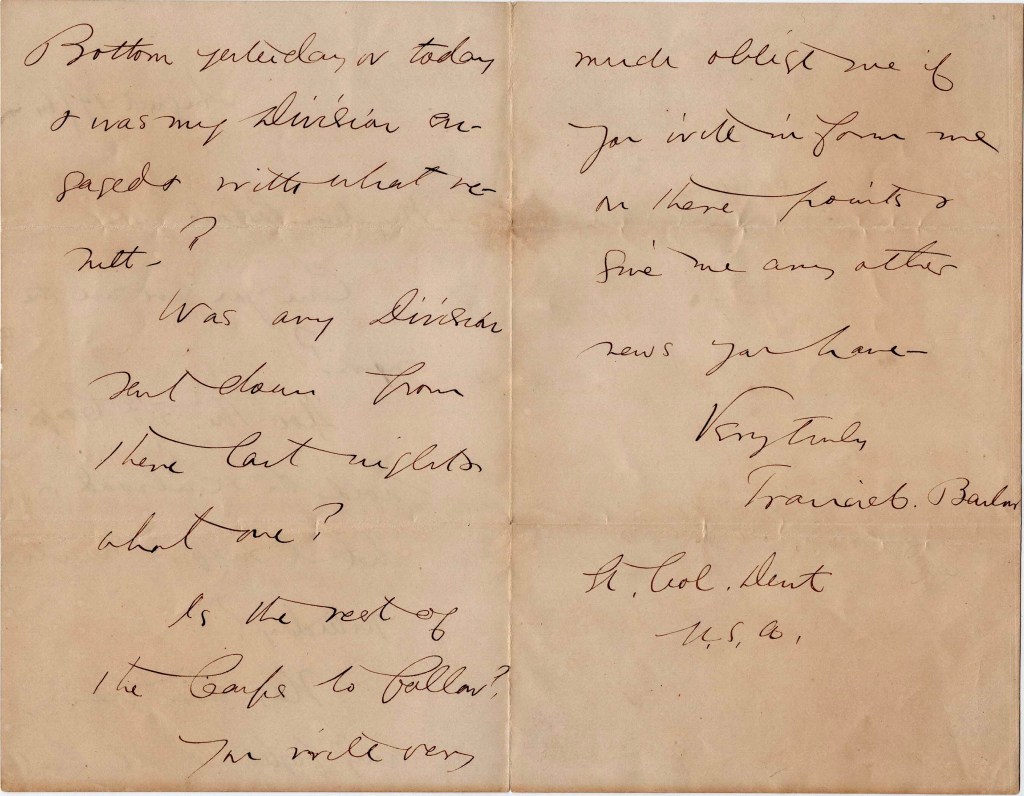

Headquarters 1st Division Ohio Vol. Inf.

Cincinnati [Ohio]

April 18, 1861

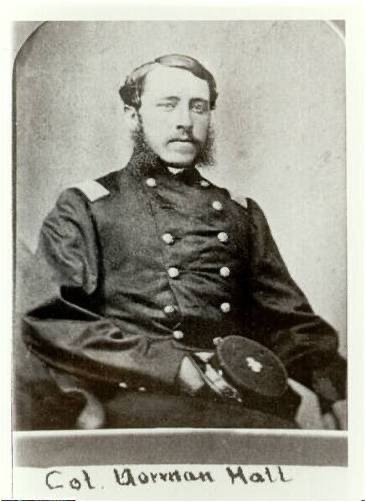

My dear Colonel.

I have neglected writing you before as I have been very busy as you may suppose as we have been called upon to defend the glorious Stars & Stripes. I conceive it my duty to stand busy then in the hour of need. I am for defending our public property at all hazards. I think it is my duty to do so. I feel the responsibility that rests upon me. I deeply regret that we are compelled to take up arms against our brothers but they have made an attack upon us and design taking possession of our National Capitol and this must never be by traitors to their country.

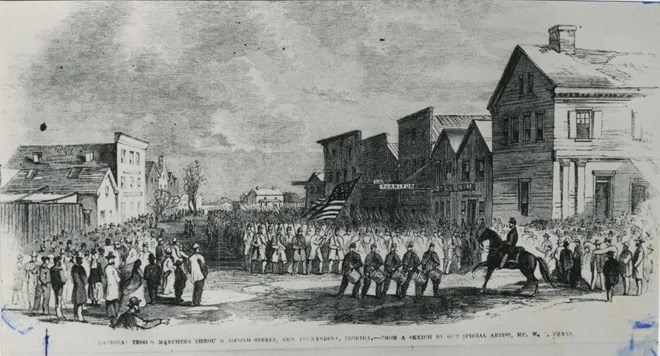

Our city is in intense excitement such as I never witnesses before. We have a large force enrolled for immediate action service. We sent off three fine companies, 80 men each this morning, and sent a fourth off, same number tomorrow. I am awaiting orders [and] do not know what moment I may be ordered away. We will have in the service some three or four thousand more by Saturday night ready to march in an hour’s notice.

My family are all well. I have not your letter with me to refer to as I have snatched a few moments of rest from my arduous duties to write these few lines to you.

I left Pear Street and the mercantile business on 1st January and have been attending to my little farm until called into my country’s service. I shall be glad to hear from you, my dear Colonel, at any time in camp or wherever it may be my fortune to be. I hope in case I am called into action you will hear a good report of me. I shall be surrounded by a brave set of fellows and shall endeavor to merit their esteem.

My respect to your family. I know if Mrs. Neff knew I was writing you she would have a message for one whom we often talk about and we [ ] as a friend. Goodbye my dear sir, and believe me your sincere friend, — Geo. W. Neff

In haste.