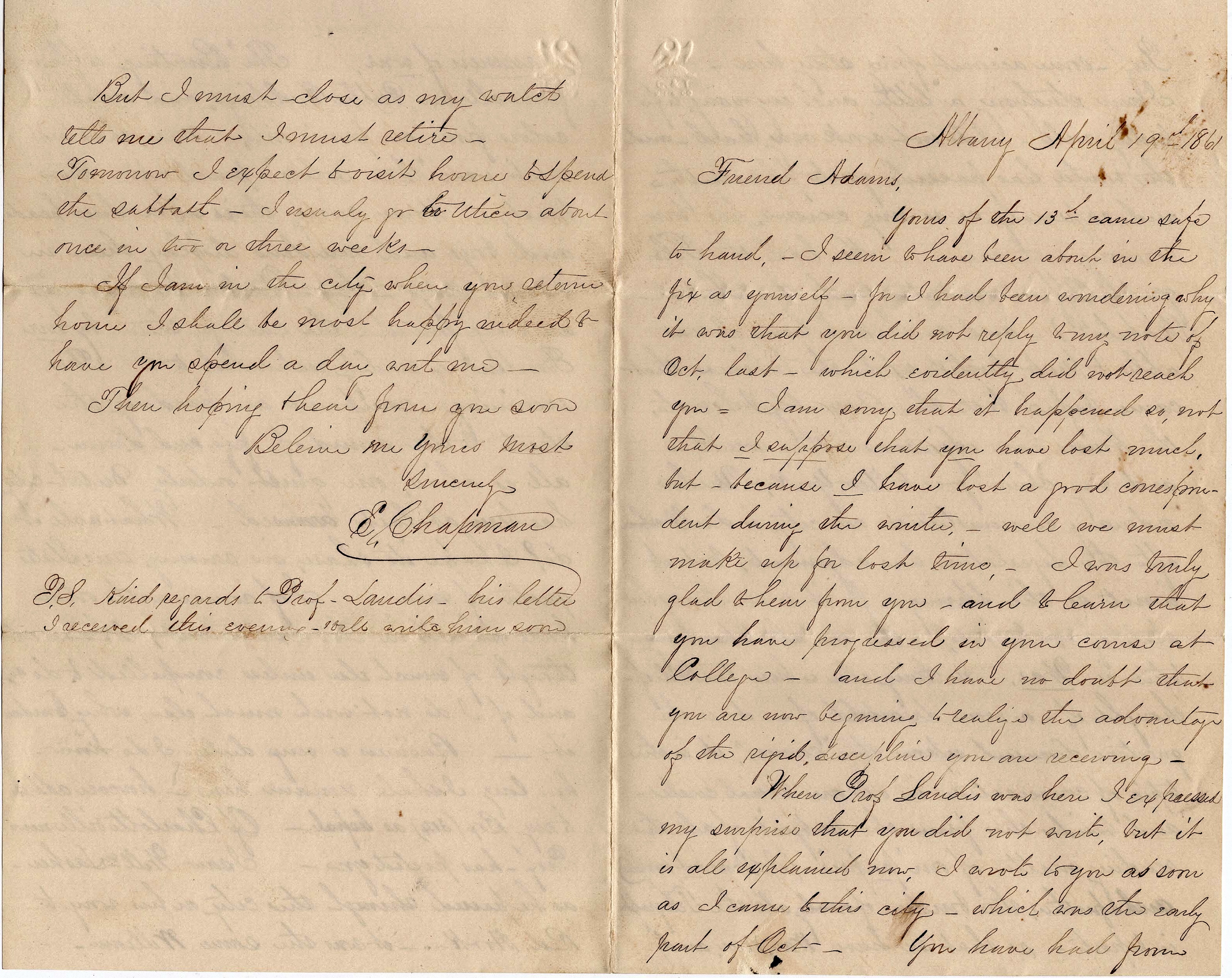

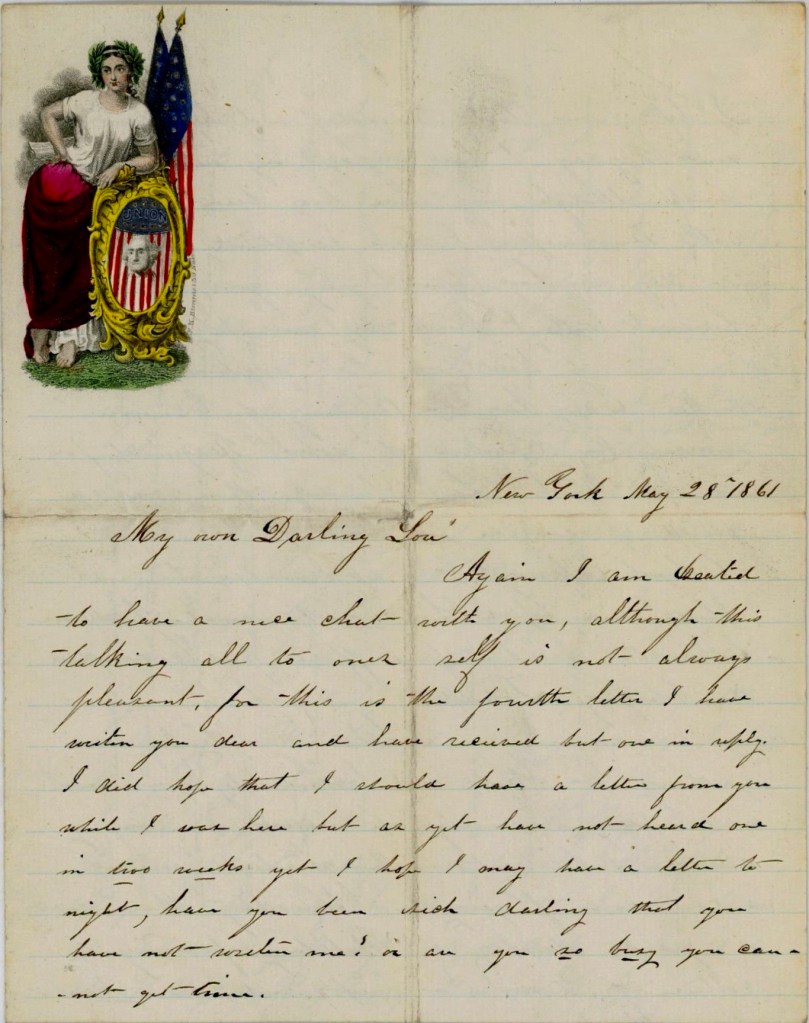

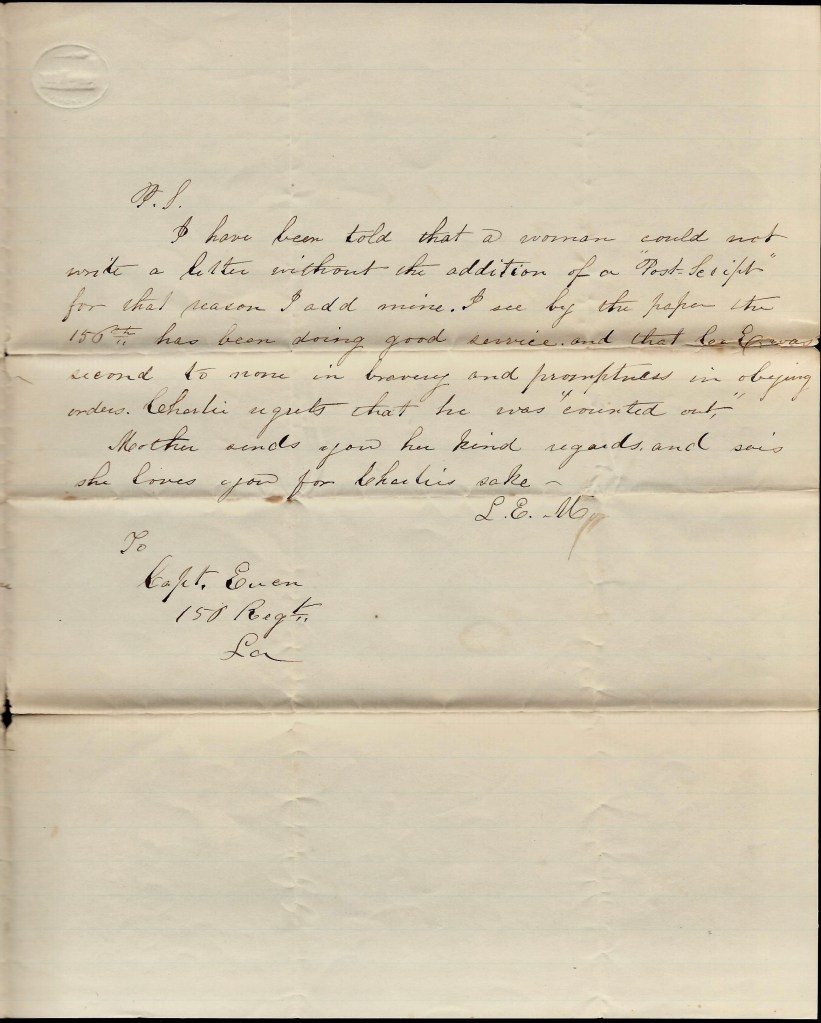

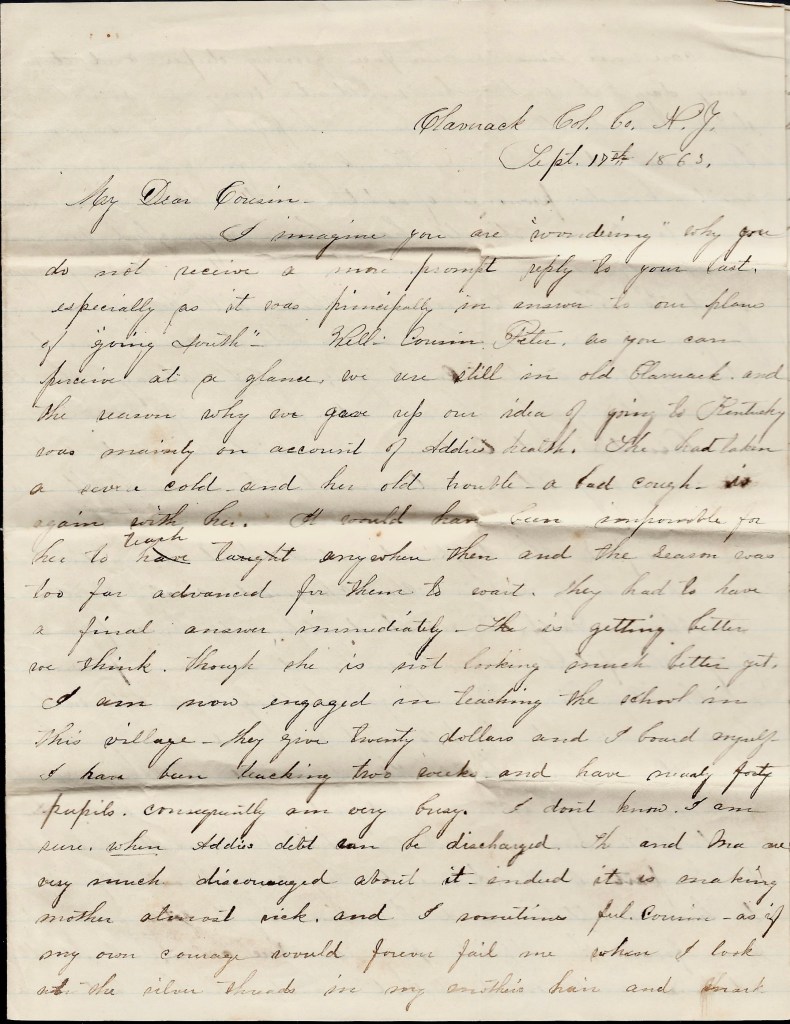

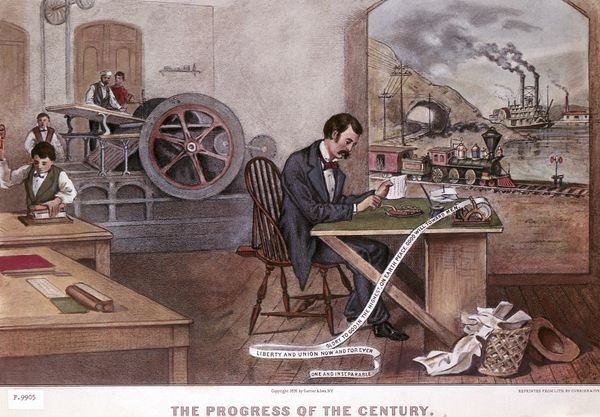

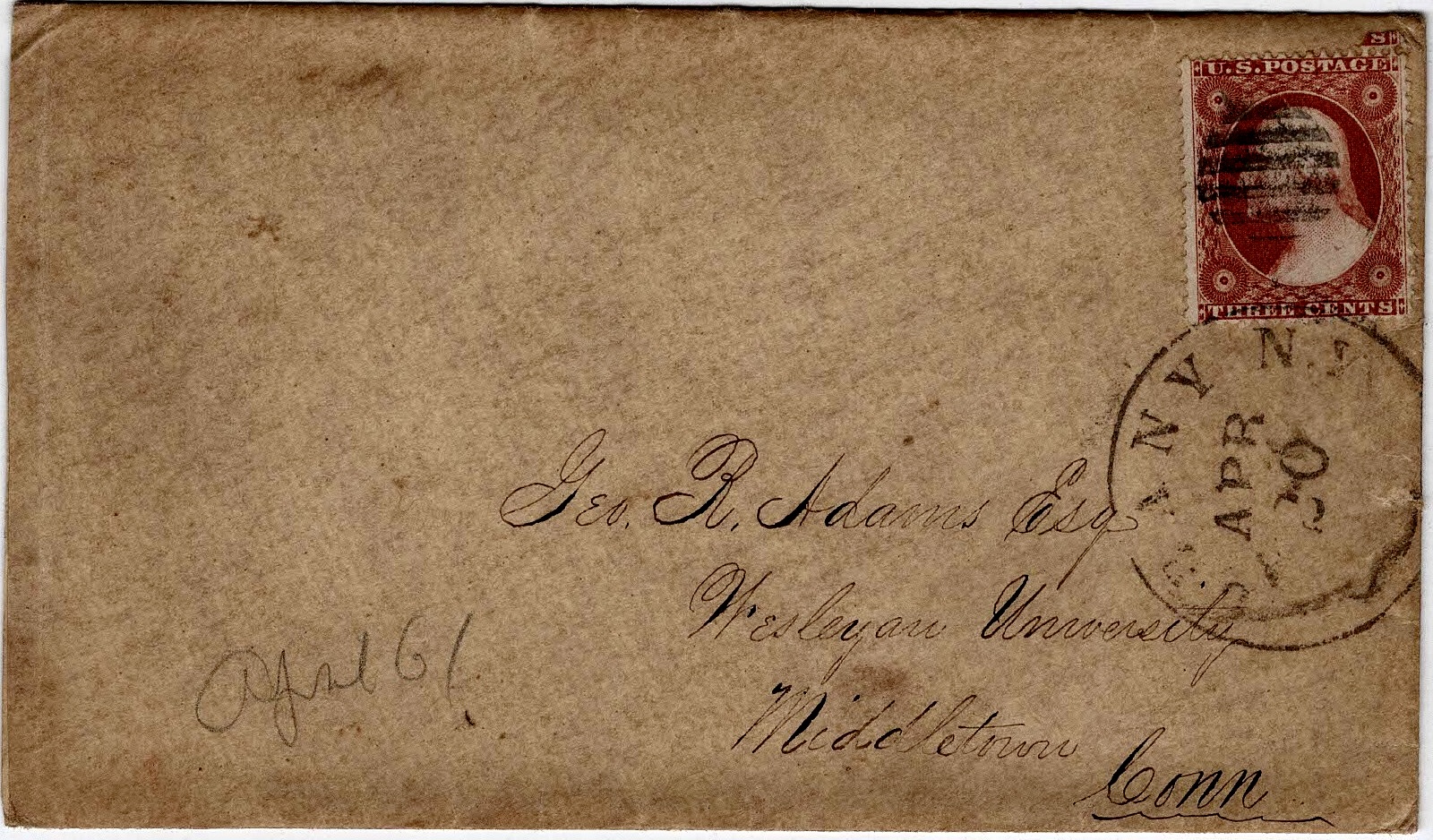

The following letter was written by Edward Chapman (b. 1836), the son of Edward Chapman, Sr. (1802-1886) and Elizabeth Burnett (1812-1874) of Utica, Oneida county, New York. Edward parents were natives of England; he was born in Nova Scotia. From his letter we learn that Edward was engaged in the telegraphic business in Albany. The 1855 N. Y. State Census informs us that he had been a telegraph operator for at least five years. By the time of the 1865 New York State Census, he was residing once again with his parents in Rochester, Monroe county, New York, where his occupation was given as “telegrapher.” Noticing that his father was also in the telegraph business, I found that Edward, Sr. had been for many years the secretary and treasurer of the New York, Albany, and Buffalo Telegraph Company which terminated business under that name in December 1863 when it merged with another company and became the Western Union Telegraph Company.

Chapman wrote the letter to George Robert Adams (1840-1915) of Charlotteville, New York, and a student at Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut., at the time. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1863 and when he was drafted, George hired a substitute to take his place while he served as the principal of the Schoharie Academy. In 1866, George was admitted to the bar in New York State and practiced law in Charlotteville and later Kingston, New York. In a letter that I transcribed in 2020, George’s mother wrote him in November 1862, “The sorrow and anguish that this war is making, no mortal tongue can tell. I am not willing that my friends should be led as sheep to the slaughter. I am willing others should have the glory of the battlefield. It is as necessary that some should remain to other places of importance to the Nation. I hope you will be a blessing to your country in some other way besides going to war.” [See—1862: Julia A. (Goss) Adams to George Robert Adams]

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

Albany [New York]

April 19th 1861

Friend Adams,

Yours of the 13th came safe to hand. I seem to have been about in the fix as yourself for I had been wondering why it was that you did not reply to my note of October last which evidently did not reach you. I am sorry that it happened so, not that I suppose that you have lost much, but because I have lost a good correspondent during the winter. well we must make up for lost time.

I was truly glad to hear from you and to learn that you have progressed in your course at College. And I have no doubt that you are now beginning to realize the advantage of the rigid discipline you are receiving. When Professor Landis was here, I expressed my surprise that you did not write, but it is all explained now. I wrote to you as soon as I came to this city which was the early part of October. You have had from Professor some account of my stay here. I am studying a little and enjoying life pretty well. I do not work very hard and the winter has passed quite pleasantly and especially so as my cousin has been rooming with me.

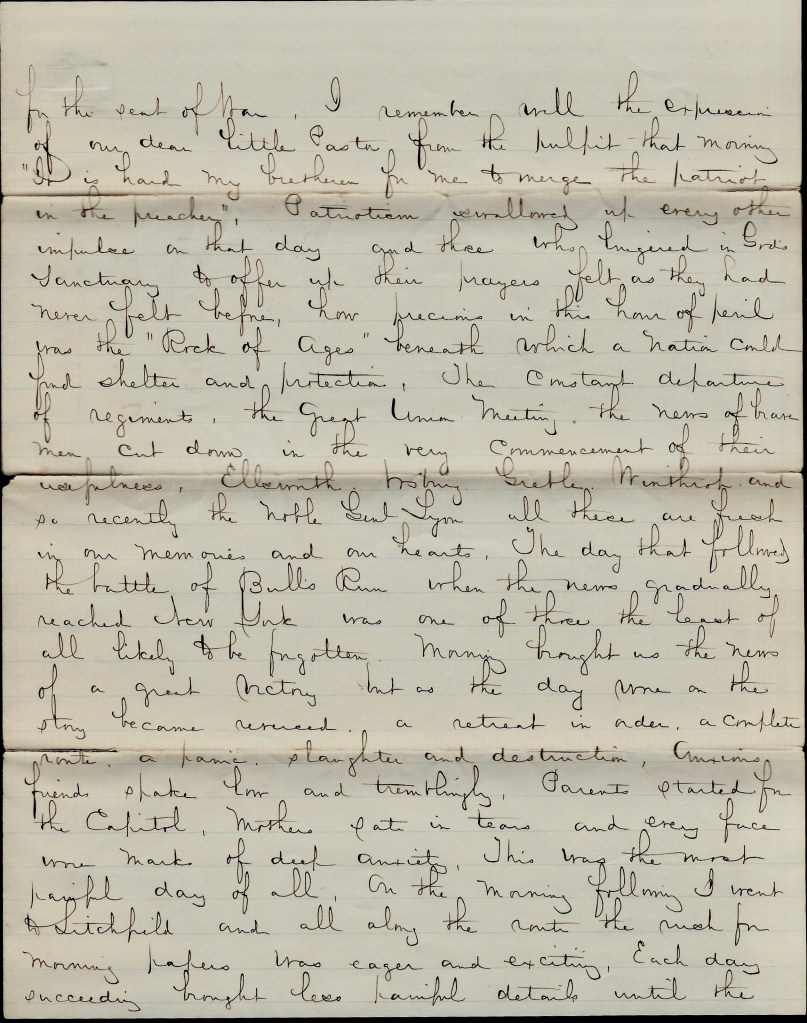

We had the telegraph office connected with the House (Capitol) and so through him I was able to keep posted about the business that came before both the Assembly and the Senate. The Houses have adjourned this week and my chum goes to New York. Under ordinary circumstances our city is dull after the Legislature has adjourned, but it is not so this Spring for it is in the highest state of excitement. The one all absorbing topic is War—nothing else is here talked of—thought of—or even dreamed of. It is the question discussed upon the “corners,” it is the topic of conversation in all our social circles, and besides this, forms the subject of all the reading matter in our papers (I. S. News not excepted), and further, the burden of all the telegraphic reports. So [in] short, we have War, War, and rumors of War.

The bunting is flying from all our public buildings and small colors from our private ones. Men that we meet wear “their colors” pinned upon their breast. Horses carry theirs upon their heads and boys and maidens display them in various ways. Several Volunteer companies are being formed. The call for them by our President is readily responded to. This evening, companies are parading the streets to the sound of the fife and drum—all is alive. Our quiet, orderly, Dutch city has been at last aroused. What will it do? I hope its share in raising our State’s quota of men.

I of course with others have shared in the excitement. I have not thought of much else unless compelled to do so, and if I do not write much else, why pardon it. Business is very dull. I do not know how long I shall remain here, however address to my Box (304) as usual.

Of Charlotteville news, Professor has posted you. I saw William Lasher as he passed through this city on his way to Red Hook. It was the same William. But I must close as my watch tells me that I must retire. Tomorrow I expect to visit home and to spend the Sabbath. I usually go to Utica about once in two or three weeks.

If I am in the city when you return home, I shall be most happy indeed to have you spend a way with me. Then hoping to hear from you soon, believe me yours most sincerely, — E. Chapman

P. S. Kind regards to Professor Landis. His letter I received this evening. Will write him soon.