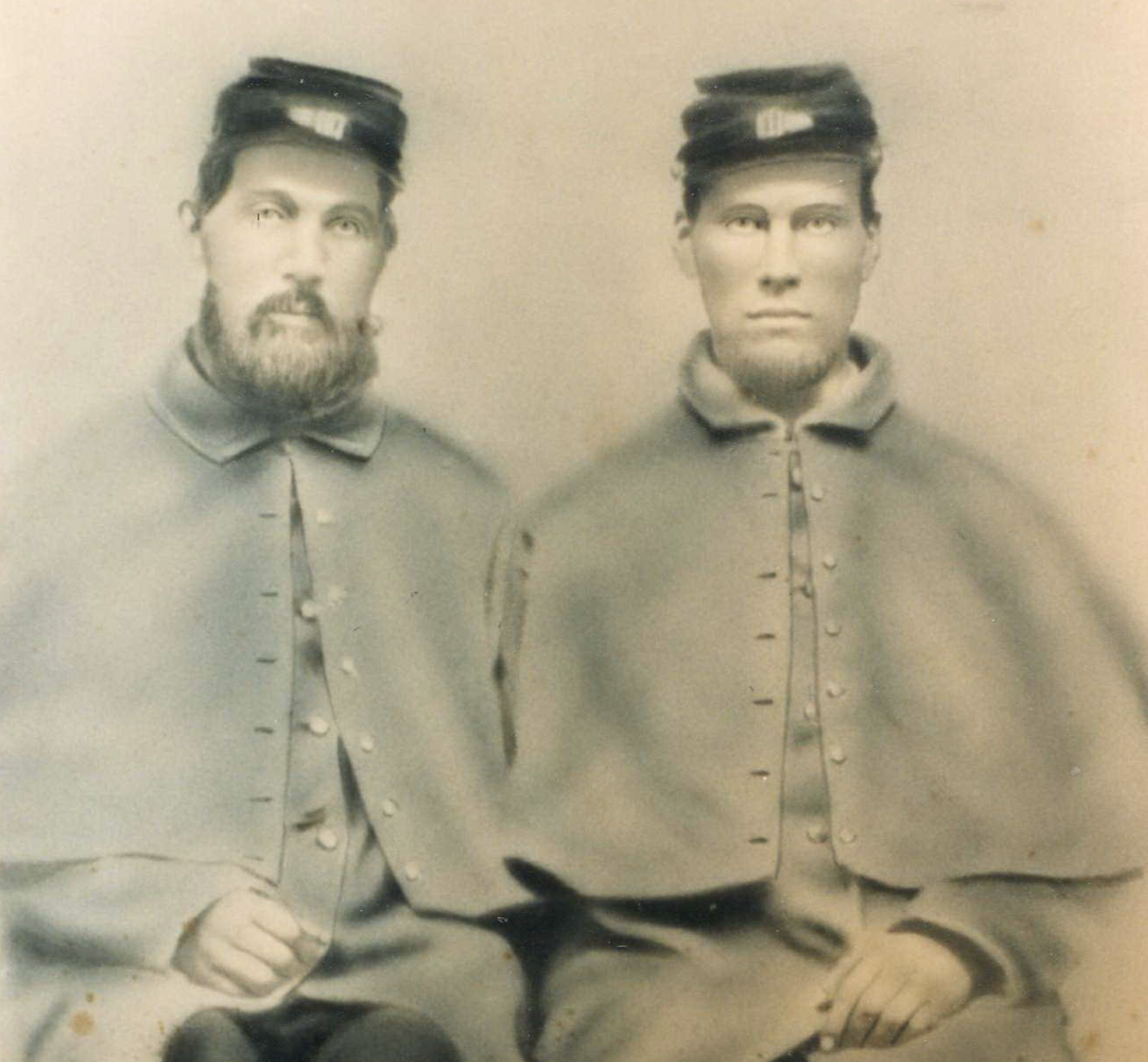

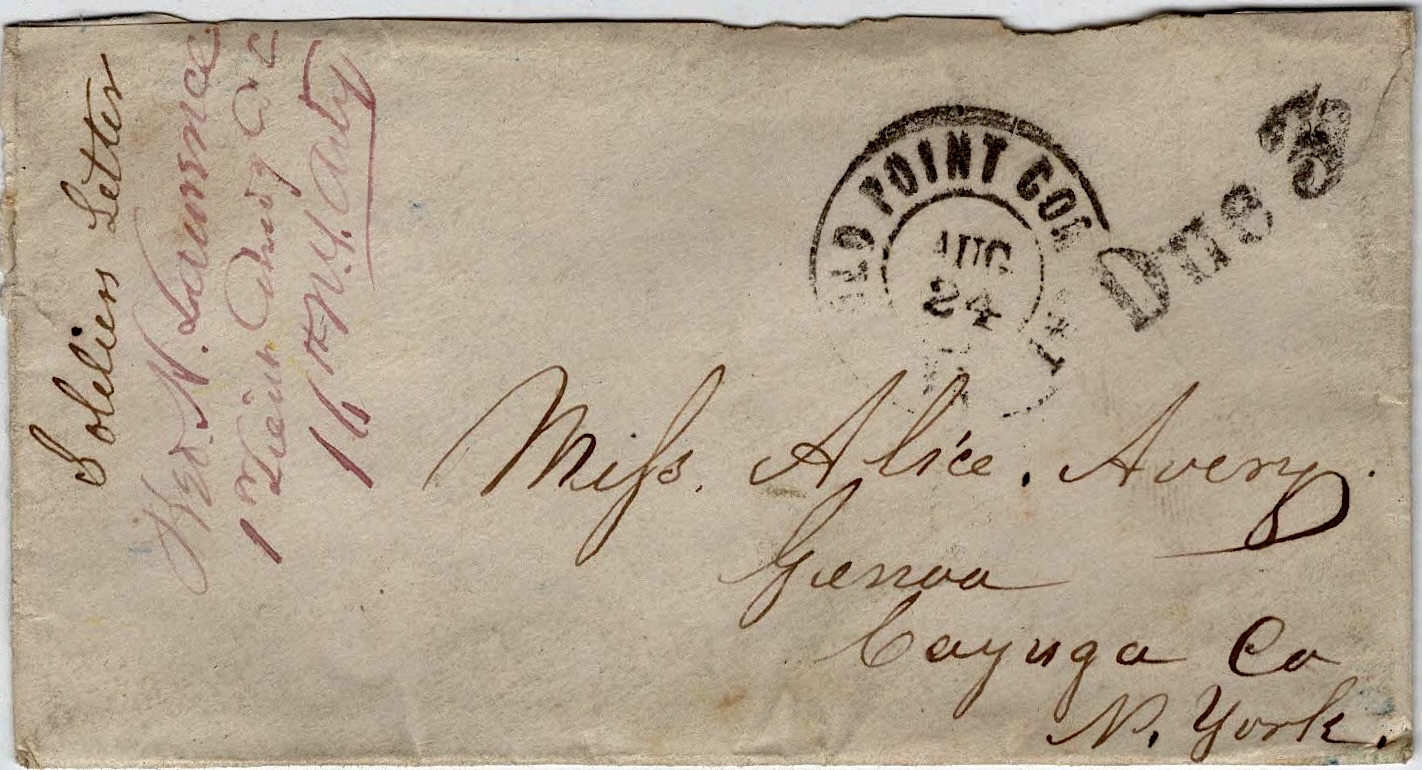

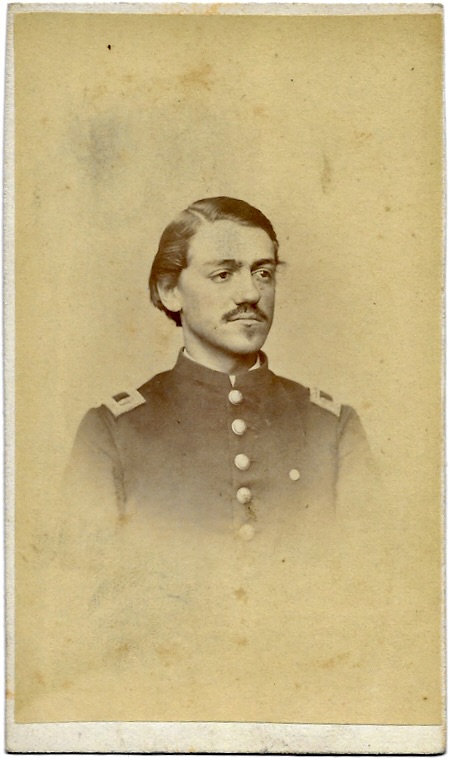

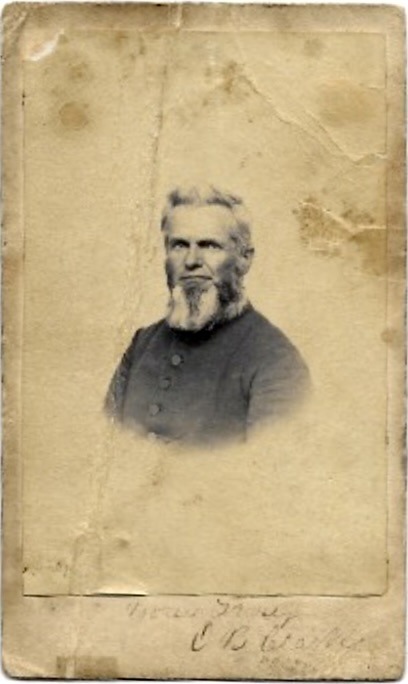

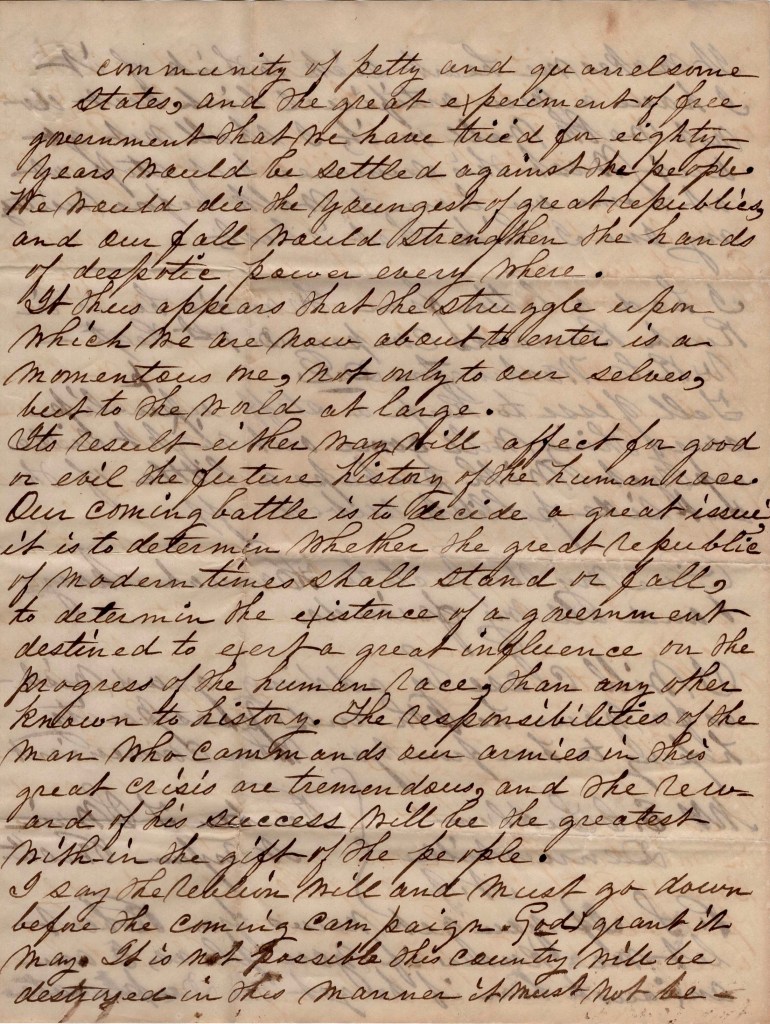

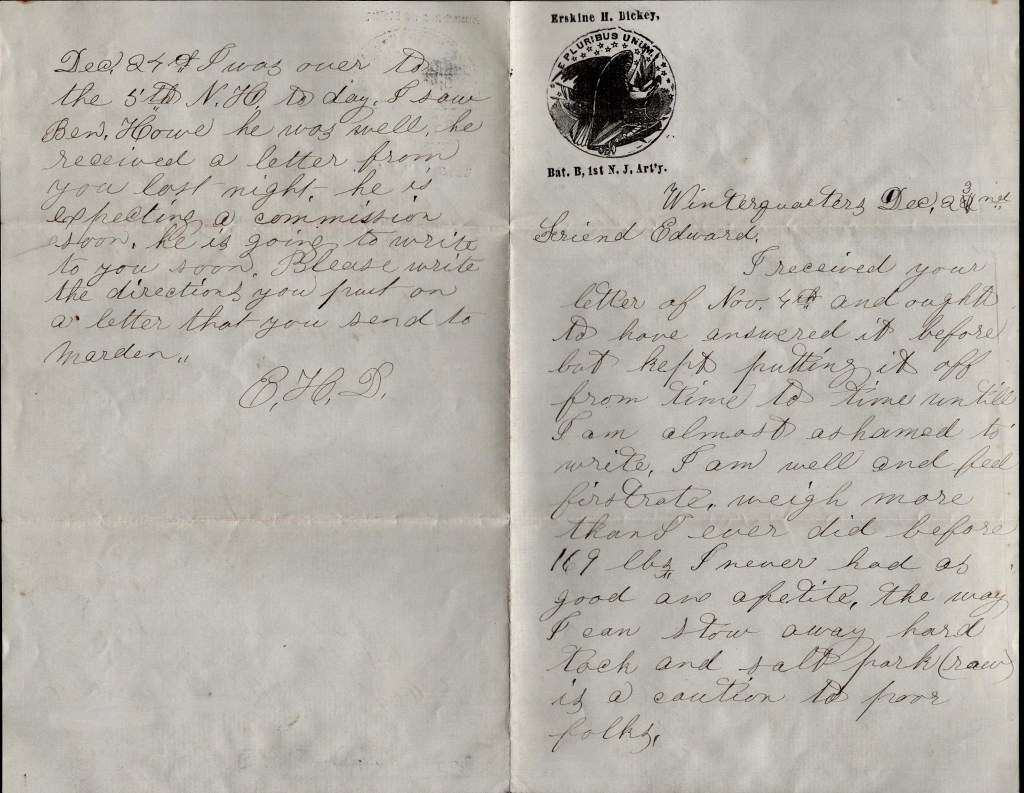

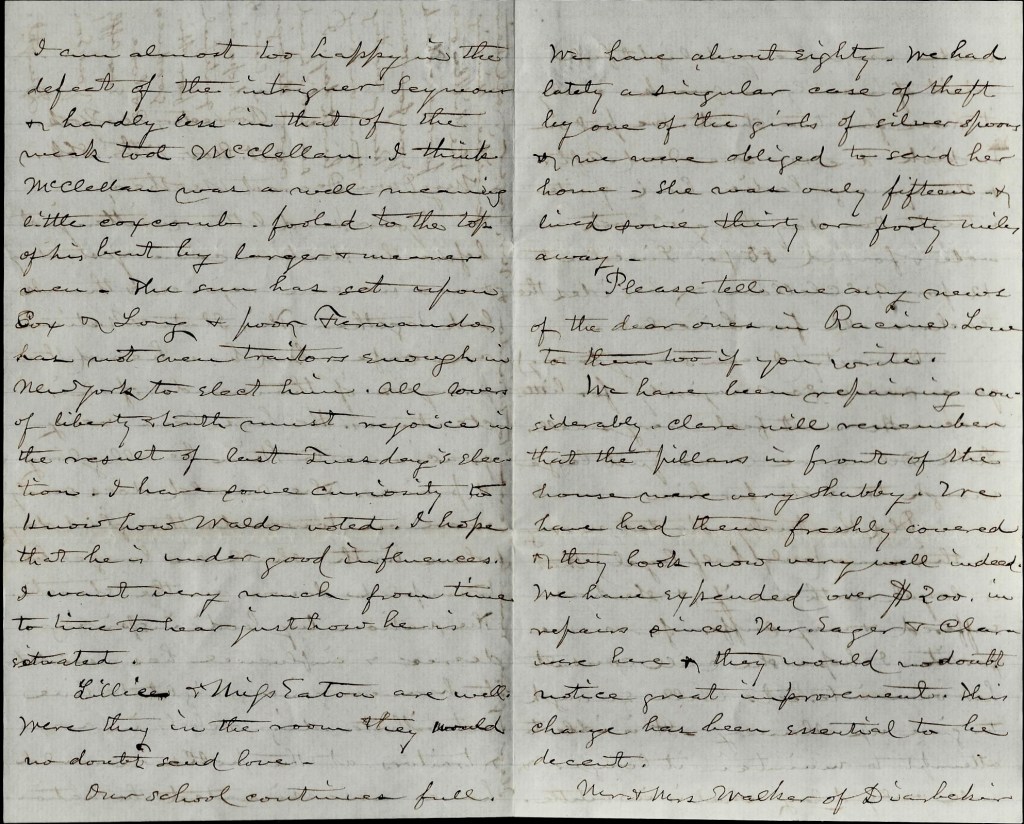

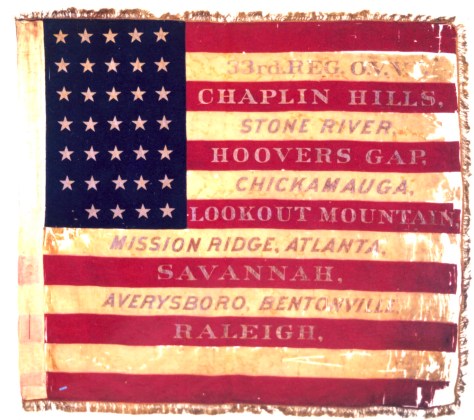

The following letters were written by William Washington Downing (1827-1908), the son of Timothy Downing (1801-1887) and Rachel Davis (1803-1883) of Pike county, Ohio. William was 34 years old when he enlisted in Co. D, 33rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry (OVI) in August 1861. Given his maturity, he quickly rose in rank to 1st Sergeant of the company and served in that capacity until August 1864 when he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant of Co. E. He mustered out as a veteran of the regiment and as Captain of Co. E, serving a total of nearly four years. After returning from the war, William relocated to Benton county, Missouri, where he farmed and lived out his days.

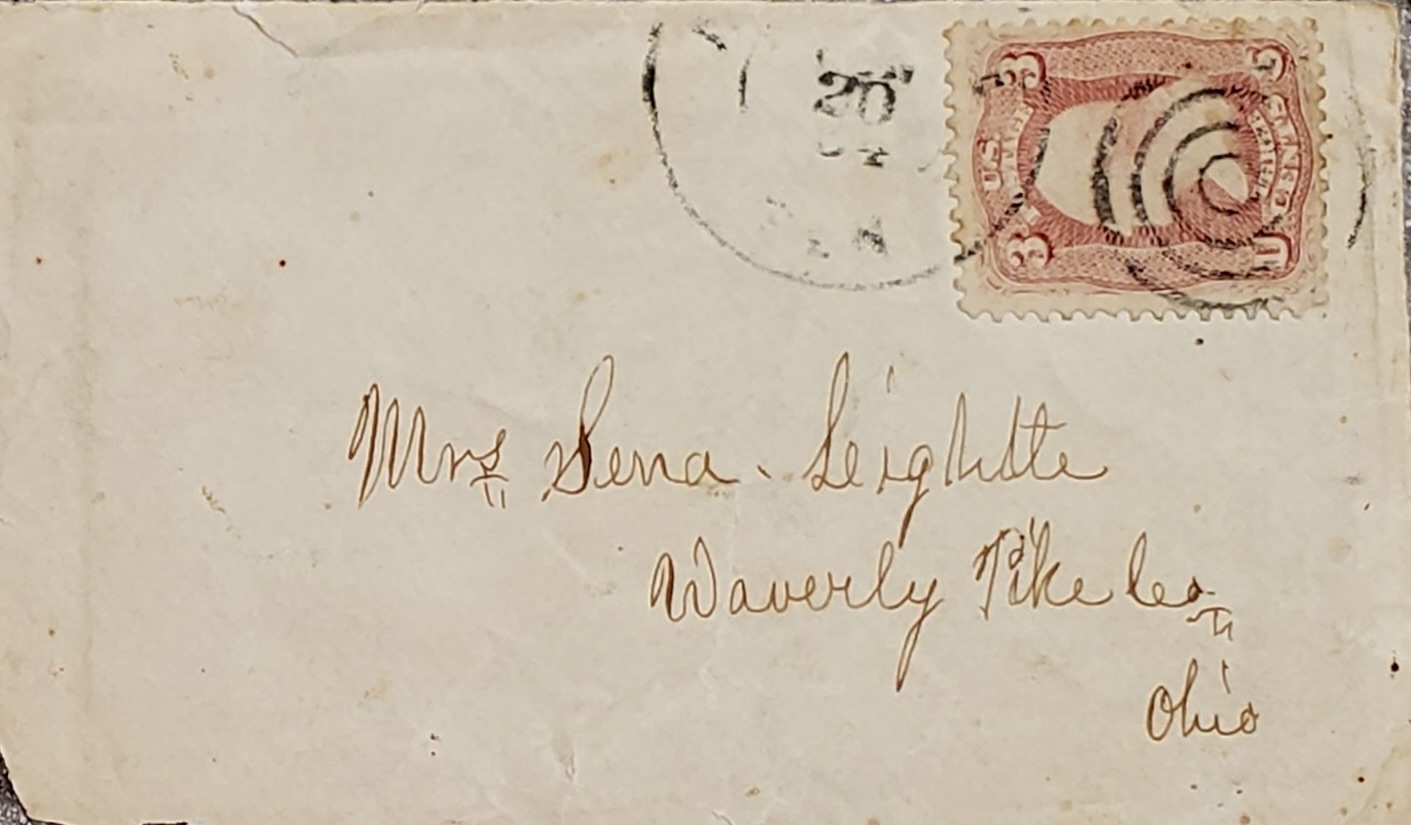

William’s younger brother, Henry Clay Downing (1844-1862), also served in Co. D with him early in the war but died of disease in August 1862. All of the letters below were written to his younger sister, Sena (Downing) Lightle (1834-1910) whose husband Peter Lightle had also served with William in the same company but was killed during the Battle of Perryville in October 1862.

William was twice married. His first wife was Mary Howard (1827-1854). His second wife was Rachel Hooper (1833-1907). A son by his first marriage, Arlington (“Arly”) Leslie Downing (1848-1929) also served in 33rd Ohio with William. He was recruited in and joined Co. D in February 1864 when he was but 16 years old.

William possessed a noteworthy and engaging style of writing that stood out among soldiers. His expressions were often humorous and unusual. And of all the thousands of Civil War letters I have transcribed, his are the first to document the use of camouflage by Union skirmishers (see letter of June 9, 1864 before Atlanta).

William’s letters are the property of Natalie Stocks who graciously made them available to Spared & Shared for transcription and publication. Sena (Downing) Lightle was her g-g-g grandmother. She inherited the letters of William, his brother Henry, and their brother in law, Peter Lightle, all of the 33rd OH Infantry Regiment, Co. D.

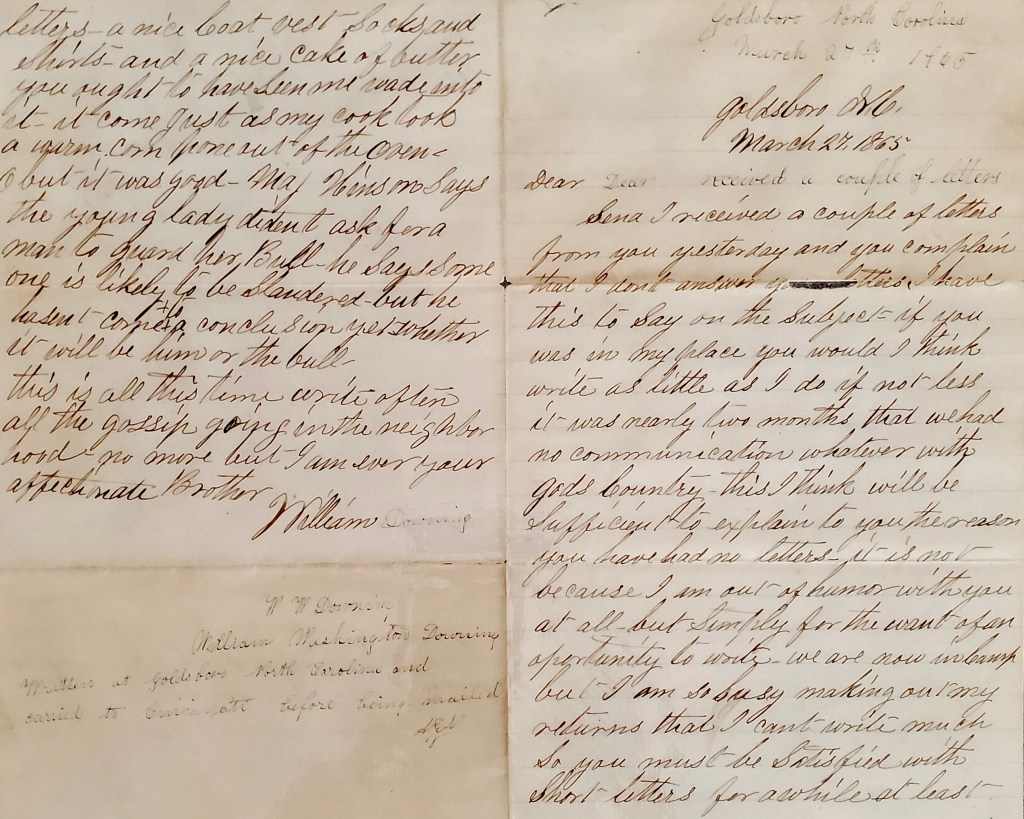

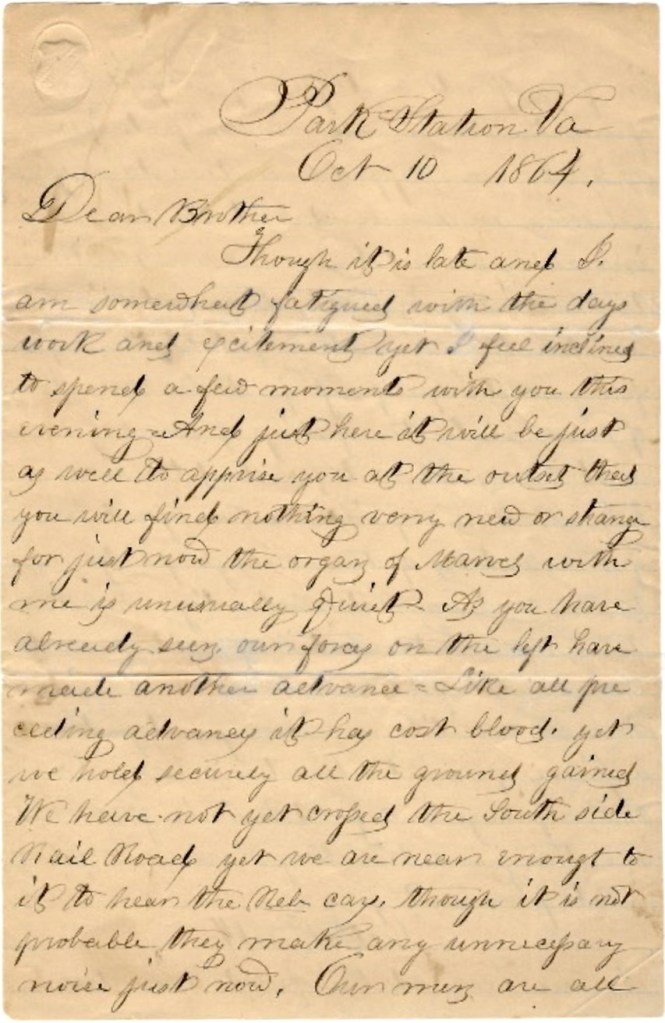

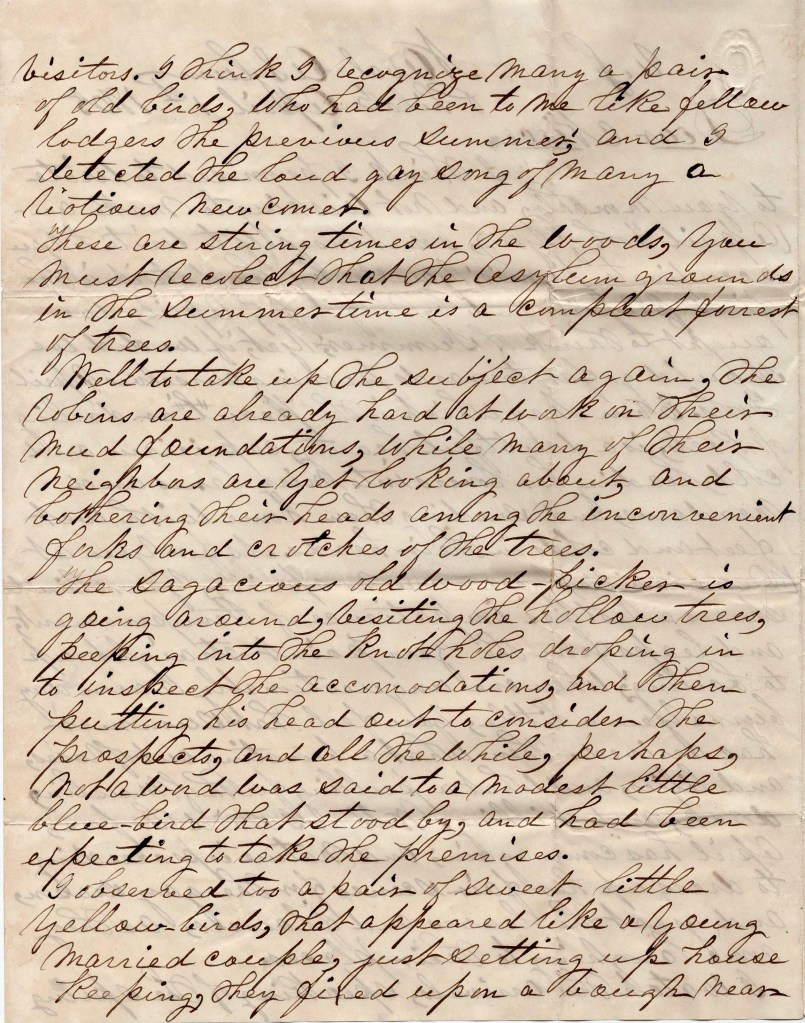

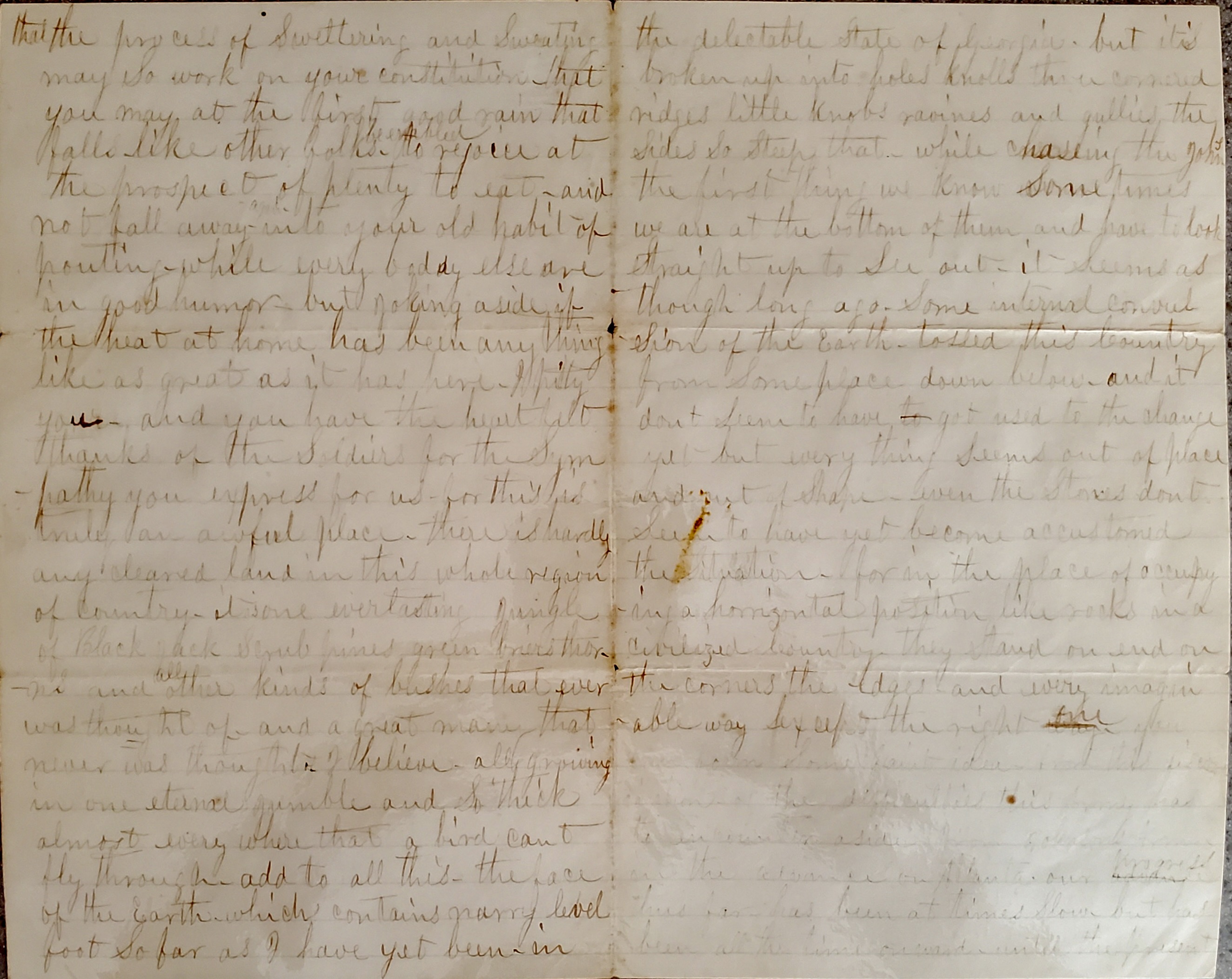

Letter 1

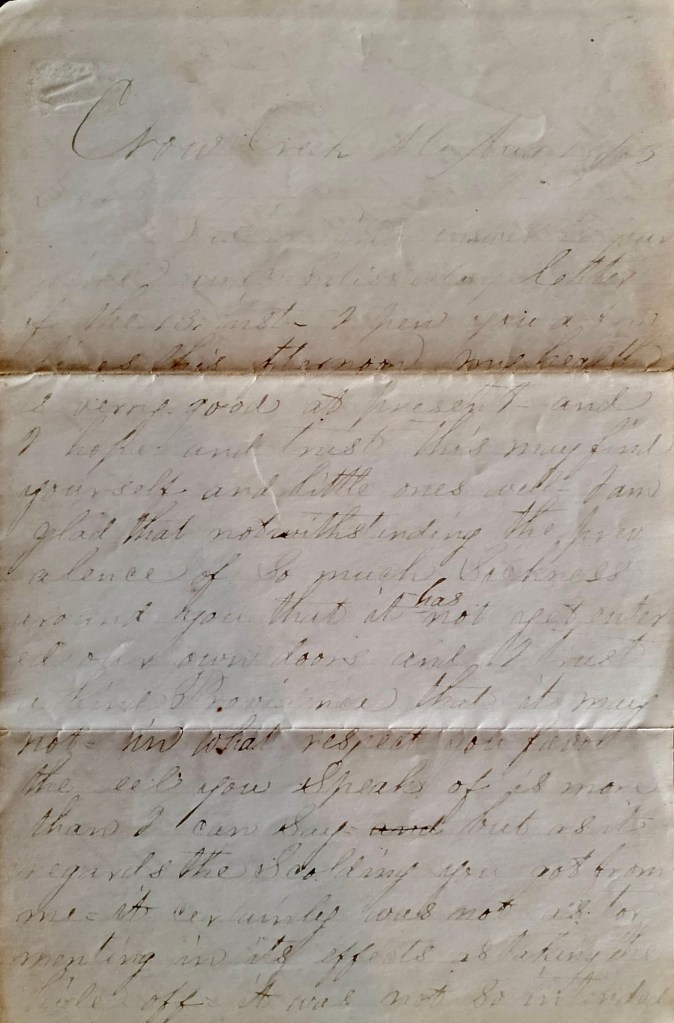

Crow Creek, Alabama

August 1863

Dear Sister,

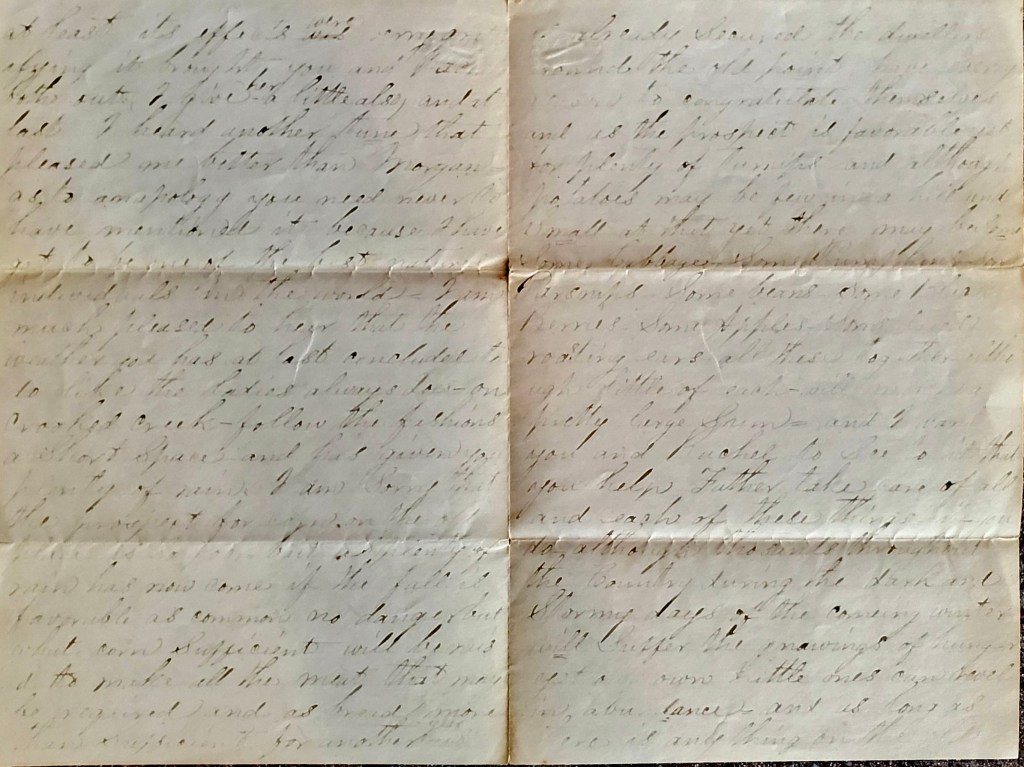

I pen you a few lines this afternoon. My health is very good at present and I hope and trust this may find yourself and little ones well. I am glad that notwithstanding the prevalence of much sickness around you that it has not yet entered our own doors and I trust a kind Providence that it may not. In what respect you favor the eel [?] you speak of is more than I can say, but as it regards the scolding you got from me, it certainly was not as tormenting in its effects as taking the hide off. It was not so intended. At least its effects were very gratifying—it brought you and Rachel both out. I give her a little [scolding] also and at last I heard another tune that pleased me better than Morgan. As to an apology, you need never to have mentioned it because I have got to be one of the best natured individuals in the world.

I am much pleased to hear that the weather god has at last concluded to do like the ladies always does on Crooked Creek—follow the fashions a short space and has given you plenty of rain. I am sorry that the prospect for corn on the old place is so poor. But as plenty of rain has now come, if the fall is favorable as common, no danger but what corn sufficient will be raised to make all the meat that may be required and as bread more than sufficient for another year is already secured. The dwellers around the old point have every reason to congratulate themselves and as the prospect is favorable yet for plenty of turnips and although potatoes may be few in a hill and small at that, yet there may be some cabbage, some plump hens, some parsnips, some beans, some blackberries, some apples, some dried roasting ears [and] all these together—although little of each—will make a pretty large sum. I want you and Rachel to see to it that you help father take care of all and each of these things. If you do, although thousands throughout the country during the dark and stormy days of the coming winter, will suffer the gnawings of hunger, yet our own little ones can revel in abundance. As long as there is anything on the old place to eat, it is my desire that yourself and little ones shall have part of it.

I will write to Henry Soerbach and request him to pay you immediately the money he owed Peter. It is not less than 6 dollars and it may be 8. Ben Lewis says Henry will know as they talked about it often while at the hospital together. Ben has forgot the amount. I guess you will have to lose what Peter’s mess owed him for the calf. Talk with them about it. They all know that they owed him but it is so messed up among hands, none seems to know just how it is. Some says they have paid theirs to some of the rest to pay over. They say they didn’t and the up shot of the matter is I don’t think they intend to pay it at all.

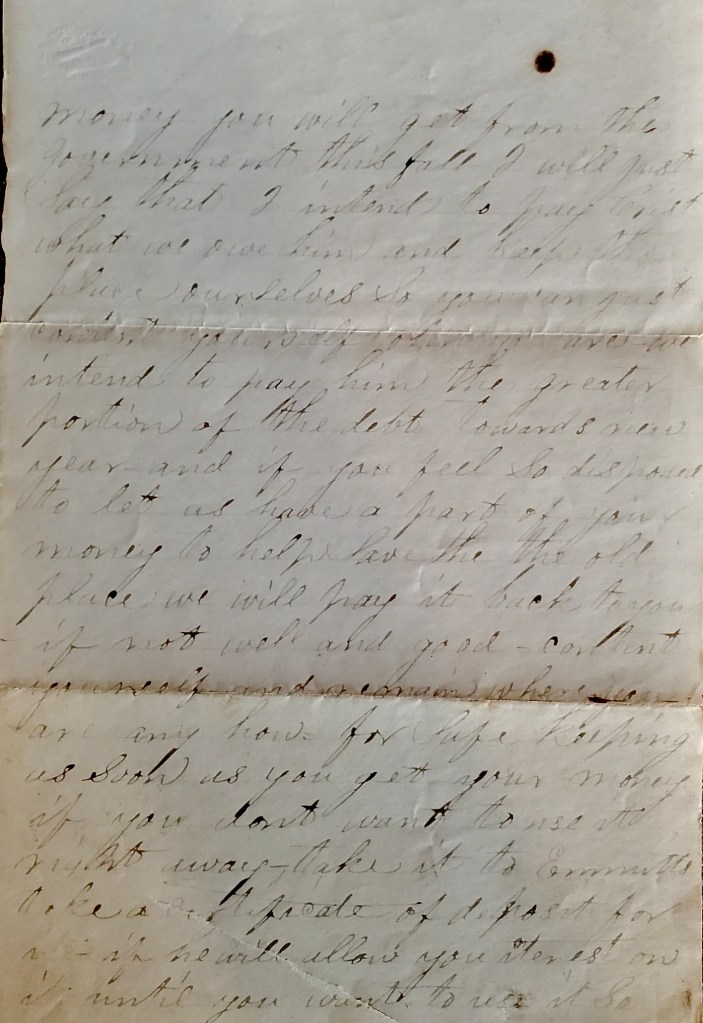

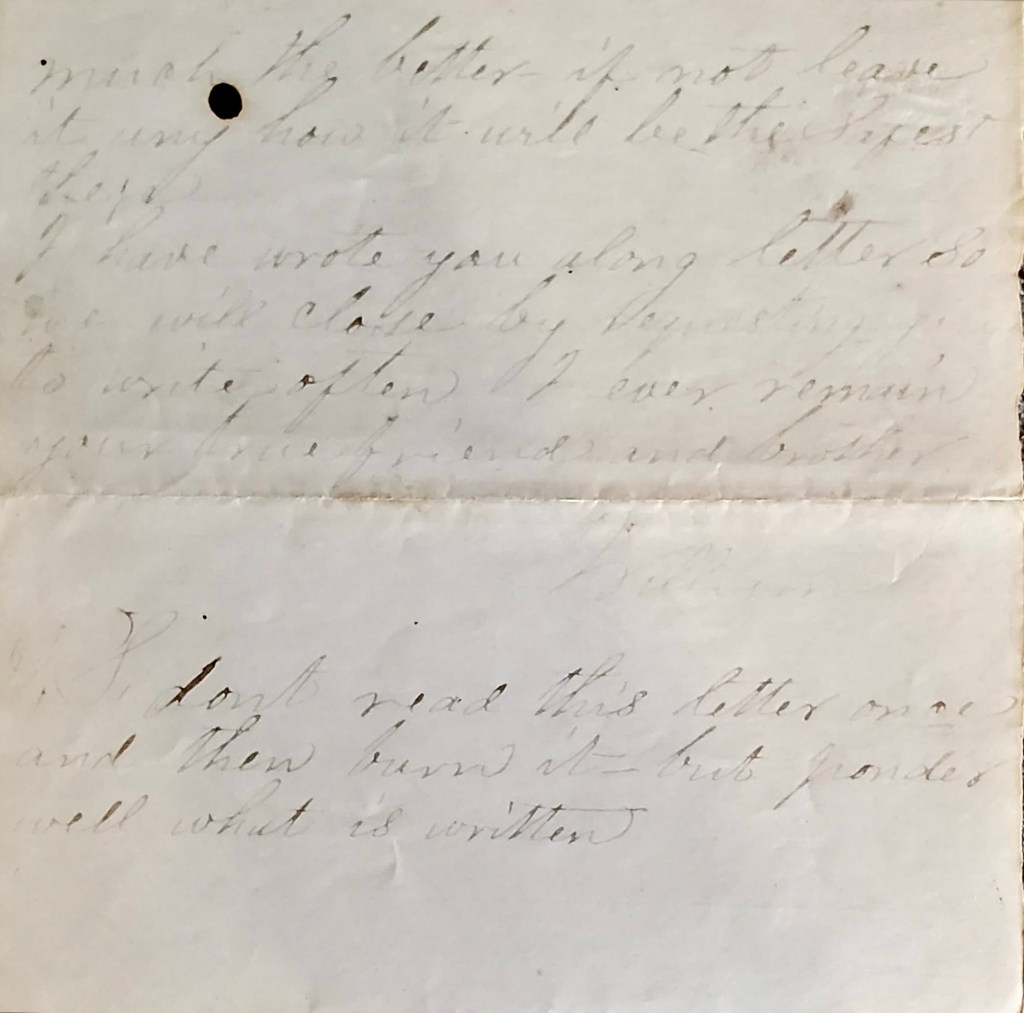

Dear sister, since you asked my advice as to what would be the best for you to do with the money you will get from the government this fall, I will just say that I intend to pay Crist what we owe him and keep the place ourselves. So you can just content yourself where you are. We intend to pay him the greater portion of the debt towards new year, and if you feel so disposed to let us have a part of your money to help save the old place, we will pay it back to you if not well and good. Content yourself and remain where you are anyhow. For safe keeping as soon as you get your money, if you don’t want to use it right away, take it to Emmitt’s. Take a certificate of deposit for it. If he will allow you interest on it until you want to use it, so much the better. If not, leave it anyhow. It will be the safest there. I have wrote you a long letter so l will close by requesting you to write often. I ever remain your true friend and brother, — William

P. S. Don’t read this letter once and then burn it, but ponder well what is written.

Letter 2

Chattanooga, Tennessee

December 30, 1863

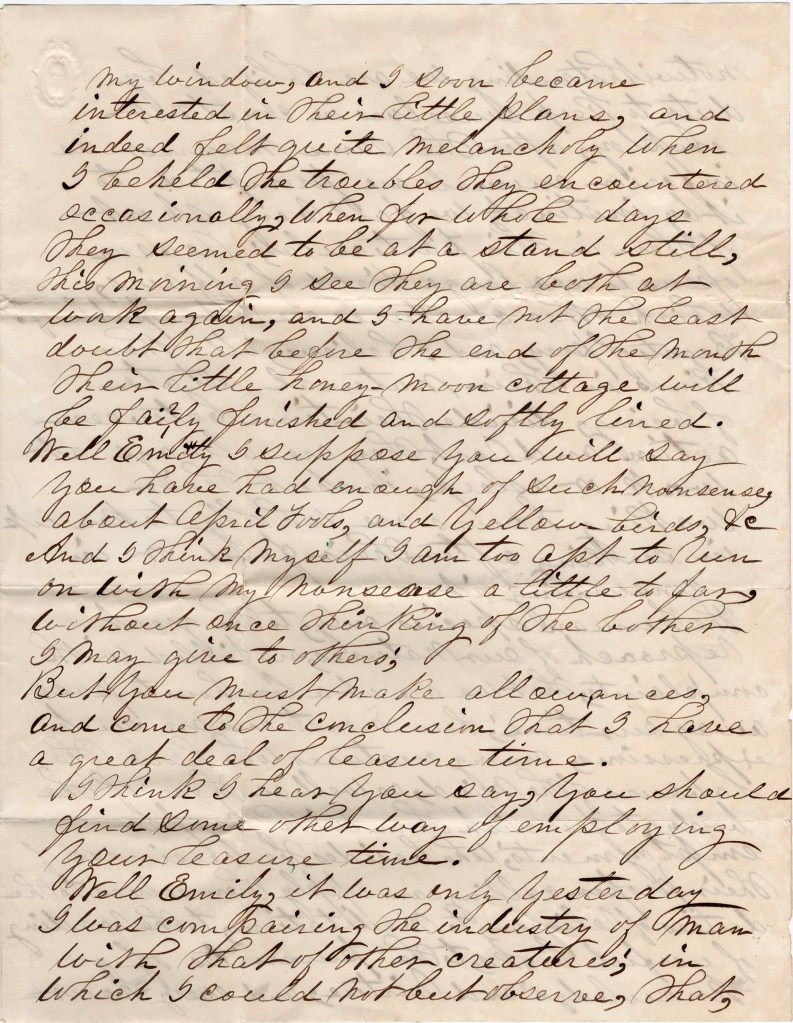

Dear sister,

In answer to your kind favor of the 20th, I pen you a few lines tonight. I had begun to think that all my friends in Pike county except Rachel had forsaken me. But night before last, I was undeceived. The letters just poured in. I sat for about two hours and read letters and felt as clever as ever Aunt Sallie did in a Methodist lovefeast. You tried to excuse yourself by saying the reason you didn’t write was that there was nothing to write about. I accept no such excuses for there was something to write about. You were all alive and well, were you not? You could have wrote and told me that certainly. And I assure you, nothing could be written that would interest me so much as that. Just let me know that are all are well at home and I can get along very well. Of course I like to hear all of the news, but I want you to make this the last time that, like Macabre, you wait for something to turn up before you write. 1

My health is only tolerable good. A spell of the headache has been bothering me for the last several days, but is better tonight. And to make htings more disagreeable, I have had muster rolls to make out, the monthly return of the company, and a great deal of other writing besides, so that I am about played out in that line. So you will have to excuse all deficiencies in this letter—both of manner and matter.

I hope this may find yourself and little ones well and hearty. Tell Allie to hold on. I will be at home in the summer and will learn him how to husk corn and pull flax and thrash soup beans too. Tell Eva that Uncle Will says she must be a good girl and learn her book and learn how to work so when mother is busy, she can get dinner, wash the dishes, and do up the work like a woman. She must learn how to knit and sew and do all kinds of work—and that she must hurry or Toey will beat her.

There is nothing whatever going on here except a little work being done finishing up the forts and the building of a bridge across the river. The cars don’t yet run nearer than 14 miles of here and the time when they will come nearer, I think, is still distant.

From the tone of your letter, you seem to think that the house I live in would not be just the thing for wet and stormy weather, seeing it is constructed out of material so frail. But I assure you that it is not only comfortable in dry weather, but is not to be grinned at even when it rains and storms either. It is not covered with coffee sacks but a first rate quality of dog tents. One side only is weather boarded with coffee sacks. They don’t keep the cold out very well, it’s true, but then they are better than nothing. But as an off set to this, I have a most charming fireplace. And the crowd around it not being large—consisting of but one individual about my size, I can make a good fire when the weather is cold, and like the Indian, sit close to it. As to the house taking fire and burning up some night while I sleep, there is not much danger from the fact that the chimney runs up to the top of the house and I never yet knew a spark to set a dorg tent afire. Id there any Sparks flying about on Crooked Creek these days or is there not?

What pity the Pike county [Peace] nuts can’t inveigle a lot of poor Devil’s into the Army in their place and let their worships remain at home. They may screw and squirm as much as they please, but their time is coming certain as the 7 year itch, and that never fails once in a lifetime nor never will.

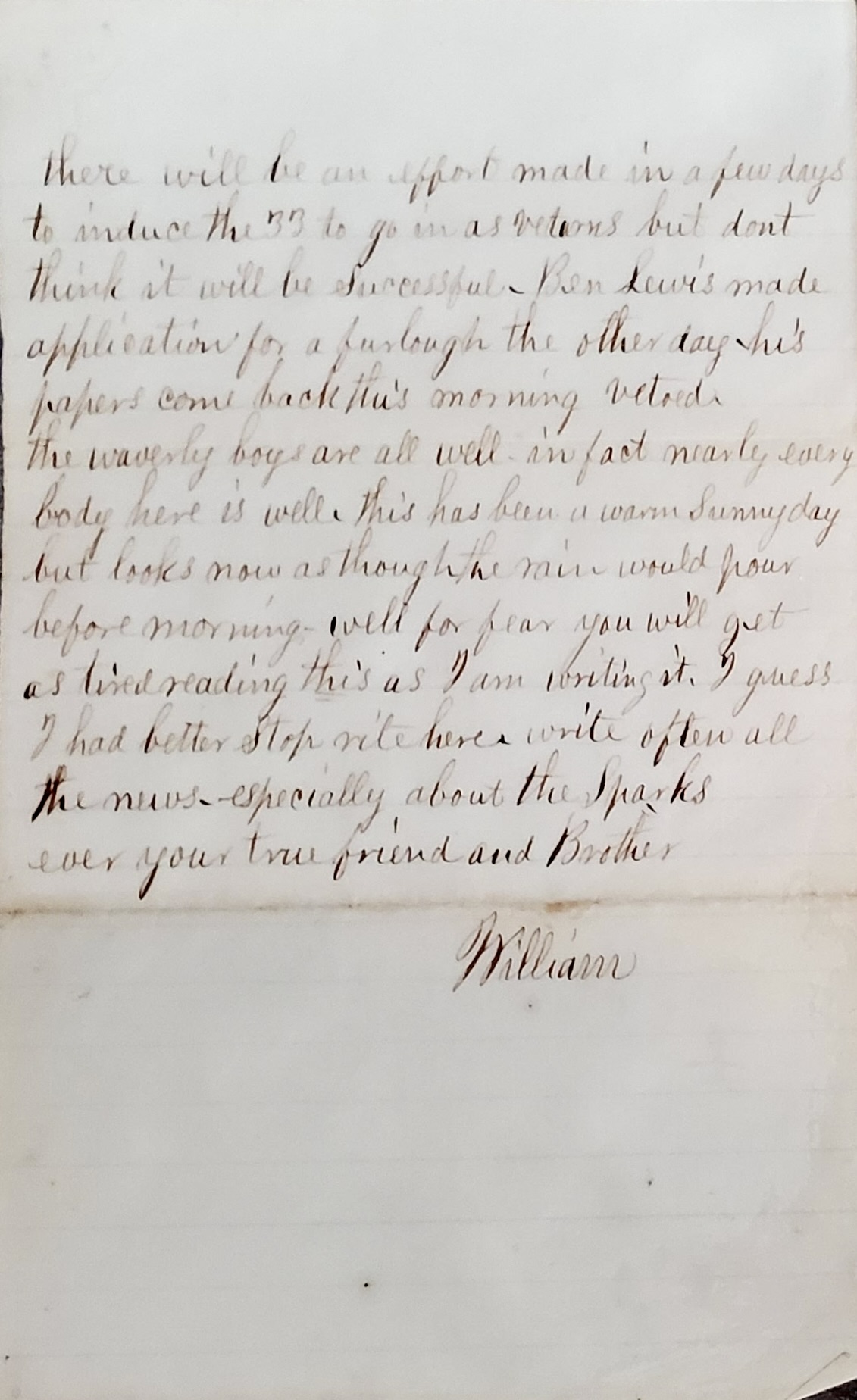

There will be an effort made in a few days to induce the 33rd [Ohio] to go in as veterans but don’t think it will be successful. Ben Lewis made application for a furlough the other day. His papers came back this morning vetoed. The Waverly boys are all well. In fact, nearly everybody here is well. This has been a warm, sunny day but looks now as though the rain would pour before morning.

Well, for fear you will get as tired reading this as I am writing it, I guess I had better stop right here. Write often all the news—especially about the Sparks. Ever your true friend and brother, — William

1 The character Mr. Micawber from Charles Dickens’s novel David Copperfield was famous for his eternal optimism and his personal maxim of “something will turn up.”

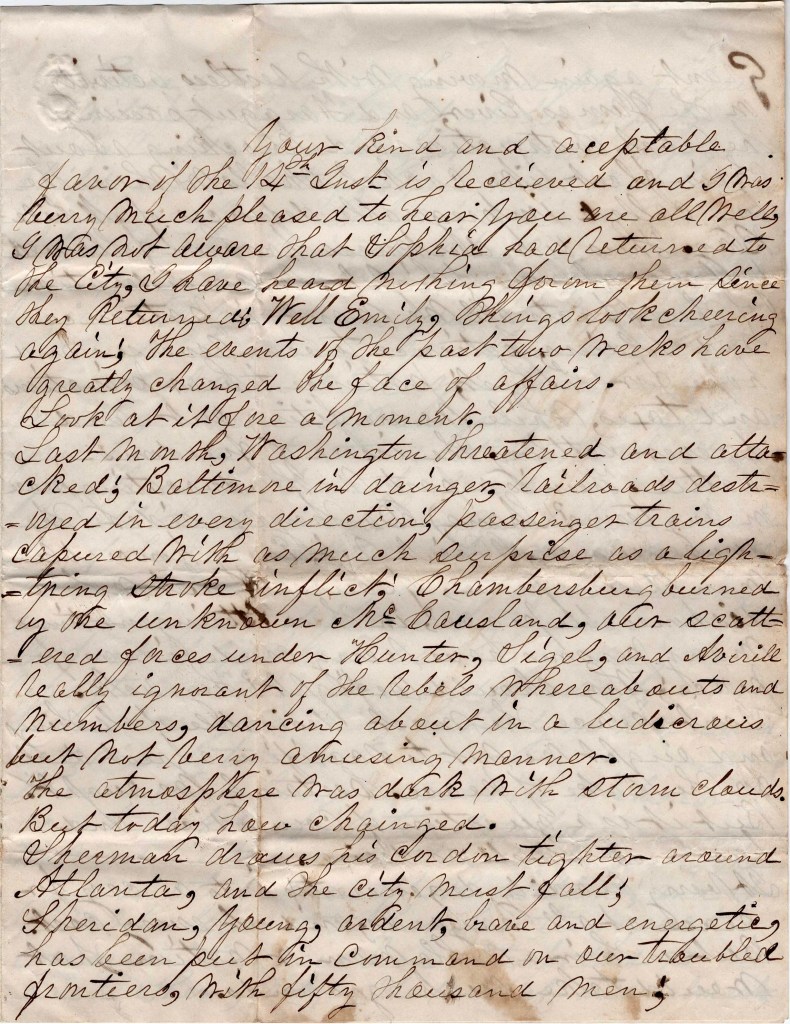

Letter 3

Chattanooga, Tennessee

January 17, 1864

Dear sister,

In answer to your kind favor of the 1st and 3rd of January, I pen you a few lines this afternoon. My health is very good and I trust when this comes to hand, it may find yourself and little ones well. From all accounts, there certainly never was such a storm ever witnessed in this country as that that begun on New Year’s eve. And it seemed to be a pretty general thing everywhere. It stormed here at the same time nearly if not quite as hard as it did there. But I reckon was not quite as cold. But the citizens say it never was any colder here in the memory of the oldest inhabitants. It is not so cold here now but is yet somewhat winterish.

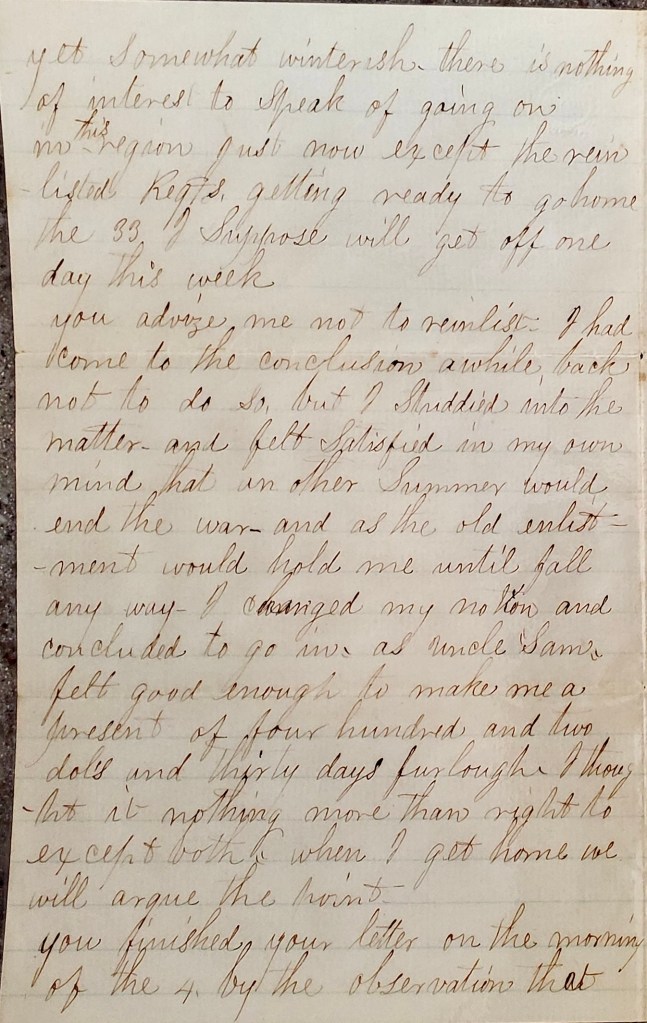

There is nothing of interest to speak of going on in this region just now except the reenlisted regiments getting ready to go home [on Veteran’s furlough of 30 days]. The 33rd [Ohio] I suppose will get off one day this week.

You advised me not to reenlist. I had come to that conclusion a while back not to do so, but I studied into the matter and felt satisfied in my own mind that another summer would end the war, and as the old enlistment would hold me until fall anyway, I changed my notion and concluded to go in. As Uncle Sam felt good enough to make me a present of four hundred adn two dollars and thirty days furlough, I thought it nothing more than right to accept both. When I get home, we will argue the point.

You finished your letter on the morning of the 4th by the observation that the snow was 4 or 5 inches deep and very cold. Query—which was cold—the snow or the weather? By the way, did the Sparks fly about during the windy weather or is there nothing on the creek anymore that produce a Spark.

Tell Eva and Allie that I will not write them any letters now but I will beat home some of these days to chat with them. The boys are all well. Nothing more. I remain your affectionate brother, — William

Letter 4

Camp in Woods, Georgia

11 miles from Marietta

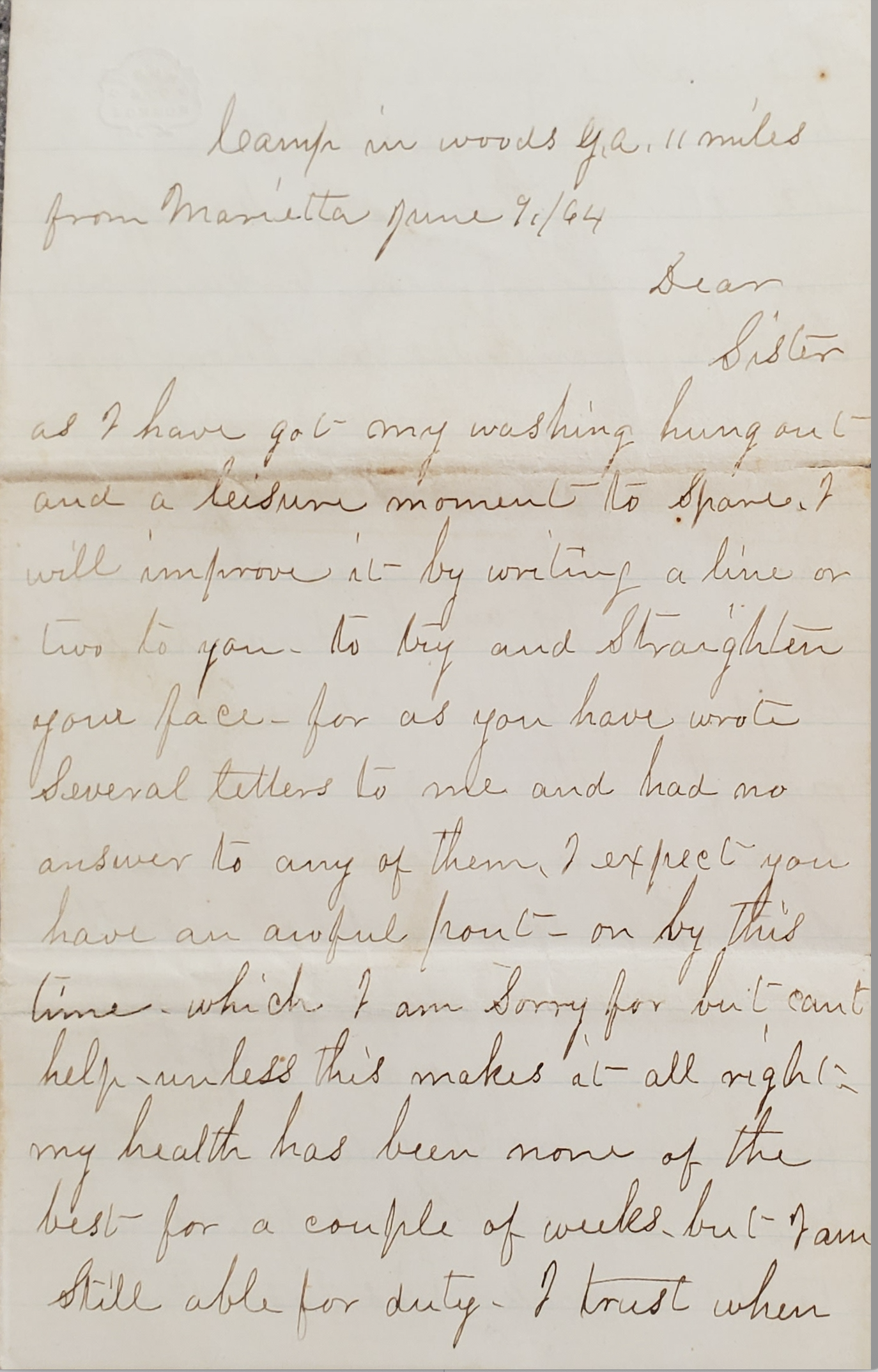

June 9, 1864

Dear sister,

As I have gopt my washing hung out and a leisure moment to spare, I will inprove it by writing a line or two to you to try and straighten your face for as you have wrote several letters to me and had no answer to any of them, I expect you have an awful pout on by this time which I am sorry for but can’t help—unless this makes it all right. My health has been none of the best for a couple of weeks but I am still able for duty. I trust when this reaches it, it may find you all at home enjoying good health and spirits.

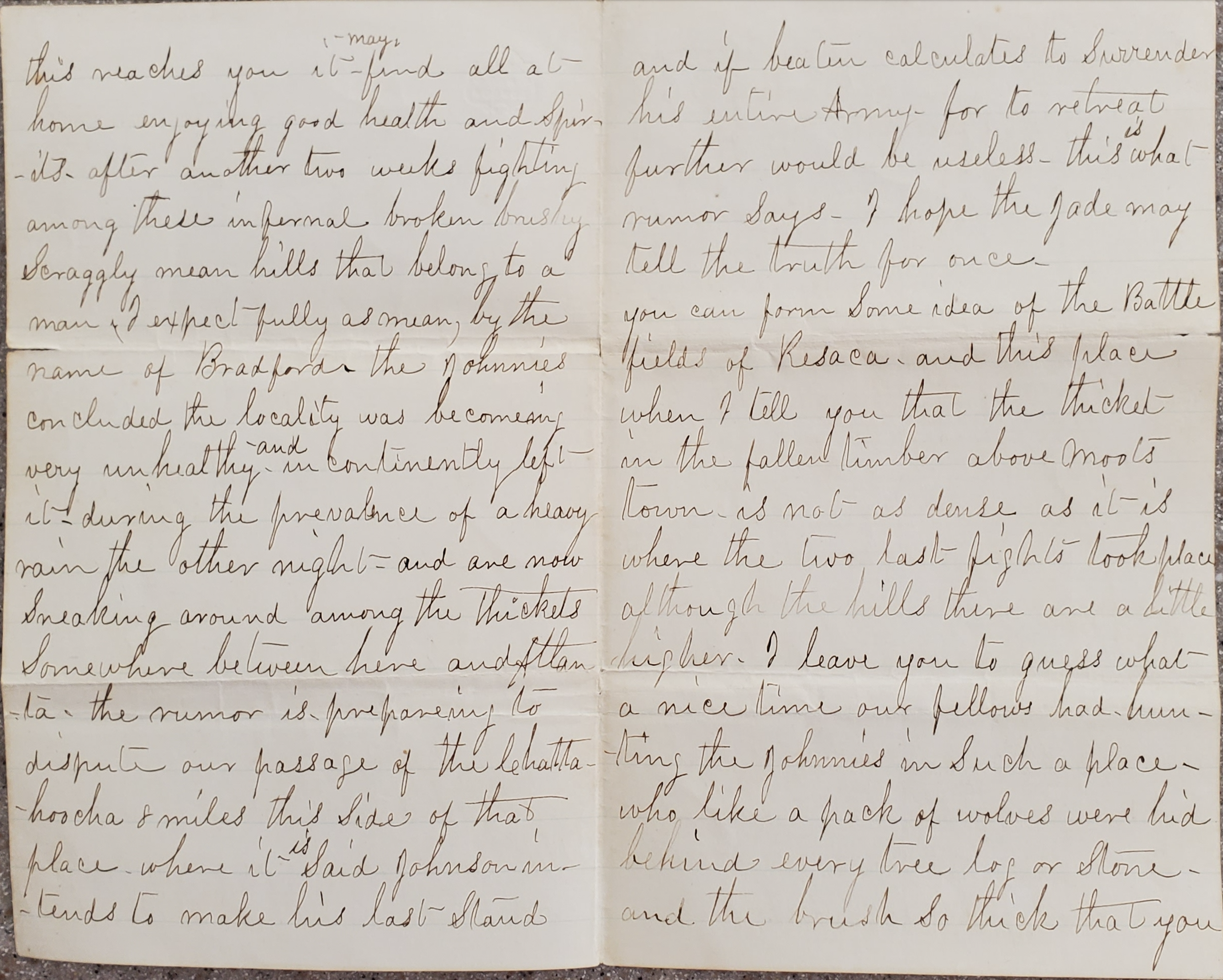

After another two weeks fighting among these infernal broken, brushy, scraggly mean hills that belong to a man—I expect fully as mean—by the name of Bradford, the Johnnies concluded the locality was becoming very unhealthy and incontinently left it during the prevalence of a heavy rain the other night and are now sneaking around among the thickets somewhere between here and Atlanta. The rumor is [they are] preparing to dispute our passage of the Chattahoochee [river] this side of that place where it is said Johnston intends to make his last stand, and, if beaten, calculates to surrender his entire army for to retreat further would be useless. This is what rumor says. I hope the jade may tell the truth for once.

You can form some idea of the battlefields of Resaca and this place when I tell you that the thicket in the fallen timber above Moot’s town is not as dense as it is where the two last fights took place although the hills there are a little higher. I leave you to guess what a nice time our fellows had hunting the Johnnies in such a place, who like a pack of wolves were hid behind every tree, log, or stone, and the brush so thick that you could not see a man until nearly on top of him. And wherever the ground was favorable, they had breastworks of logs and earthworks thrown up, and in making our approaches our men several times unwittingly run against them and suffered heavy loss in consequence. This is the way the 23rd [Army Corps] was cut up so badly. The officer in charge of the Brigade, like a fool, run them into it and he might just as well have run them into Hell five at once.

Hazen’s Brigade of our Corps was served exactly the same and suffered accordingly. Here in these two foolish enterprises hundreds of men were killed and wounded and neither of them added one iota towards the defeat of the Rebels. It is a nice job driving the scoundrels out of these places as well as a work of time, but our fellows goes at it like working by the month.

The skirmishers before they start in, breaks a lot of twigs with the leaves on and sticks them all over the front of their persons, being very careful to stick a large bunch in the hat band in front. The idea is to look as much like a bush as possible to fool the Johnnies, each being fixed up in green. They start in walking as though on eggs [but] in a very short time the guns begin to crack and bullets whistle. The Johnnies hang to their thickets to the last moment. But the Yankees, like Old Virginia, never tires and they have to get out of it at last, fast as their legs can carry them. People at home may think that the good work goes on very slow in this direction, if any such there be. They know nothing about what the difficulties are. When you read this, you will have some idea of them. But thank Heaven, we are gaining ground and the further we advance south, the more open the country becomes. And as these difficulties lessen, the more telling will be our blows on the Rebel armies and I think by the time we reach Atlanta and Montgomery, those armies will be about used up and dispersed. And then the end approaches, for just as soon as this and Lee’s army, or either of them, is dispersed, the Confederacy is gone beyond the hope of recovery by Davis, the Devil, or any other man. Mark that, and I am satisfied that four months is ample time in which to accomplish the good work. And if the hard fighting is not over within that time, I miss my guess—that’s all.

Arly is well and lively as a cricket. He sends his love and word to Lily [and says] that he will not write until we get into camp but when that will be, she knows as well as he. The rest of our boys are well except James Hirn. He is complaining.

The weather is showery and very hot but the health of the troops generally is very good. There is more apples, peaches, black band huckleberries here than you ever heard tell of, and all nearly ripe. The people here lives just as the first settlers in Ohio used to. Every family has a set of hand cards for wool and cotton, a spinning wheel, reel and loom. They raise and manufacture near about everything they eat and wear. It is the happiest life people can live and I long for the time to come when I can enjoy the blessing of such a life myself for I assure you, that the din and confusion of the crowded camp as well as the crash and roar of battle begins to worry me—and I feel as though I wanted to be more to myself, or where I will not be disturbed by any noise more harsh than that heard on and around a well regulated farm. Such as are made by domestic fowls and animals or the voices of those I love.

Happy life—how I long for your return once more. How keenly and with what relish can I enjoy your blessings in time to come. Dear sister, I expect I have wrote all and more than will interest you, so I think we had better close for this time by requesting you not to get in the pouts any oftener than once a week if you don’t get any letters from me for I assure you that materials and opportunities for writing letters here are of the most limited character. And if you don’t get letters from me, don’t make it an excuse for not writing on your part. I ever remain your true friend and brother, — William

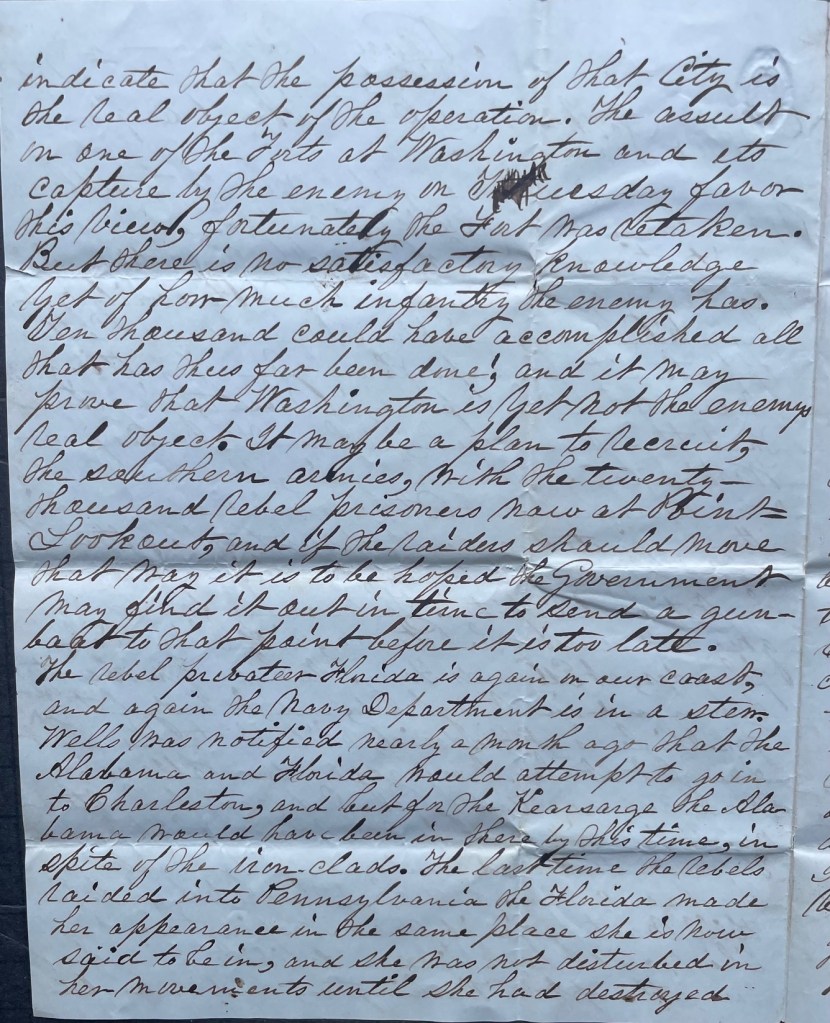

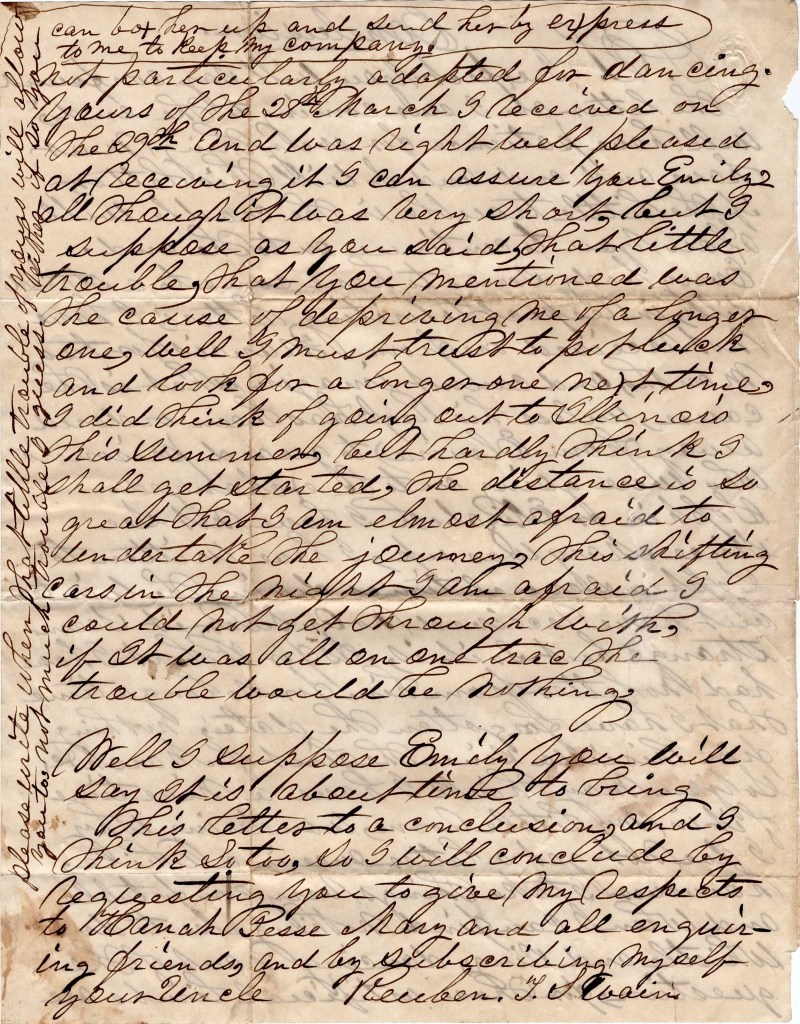

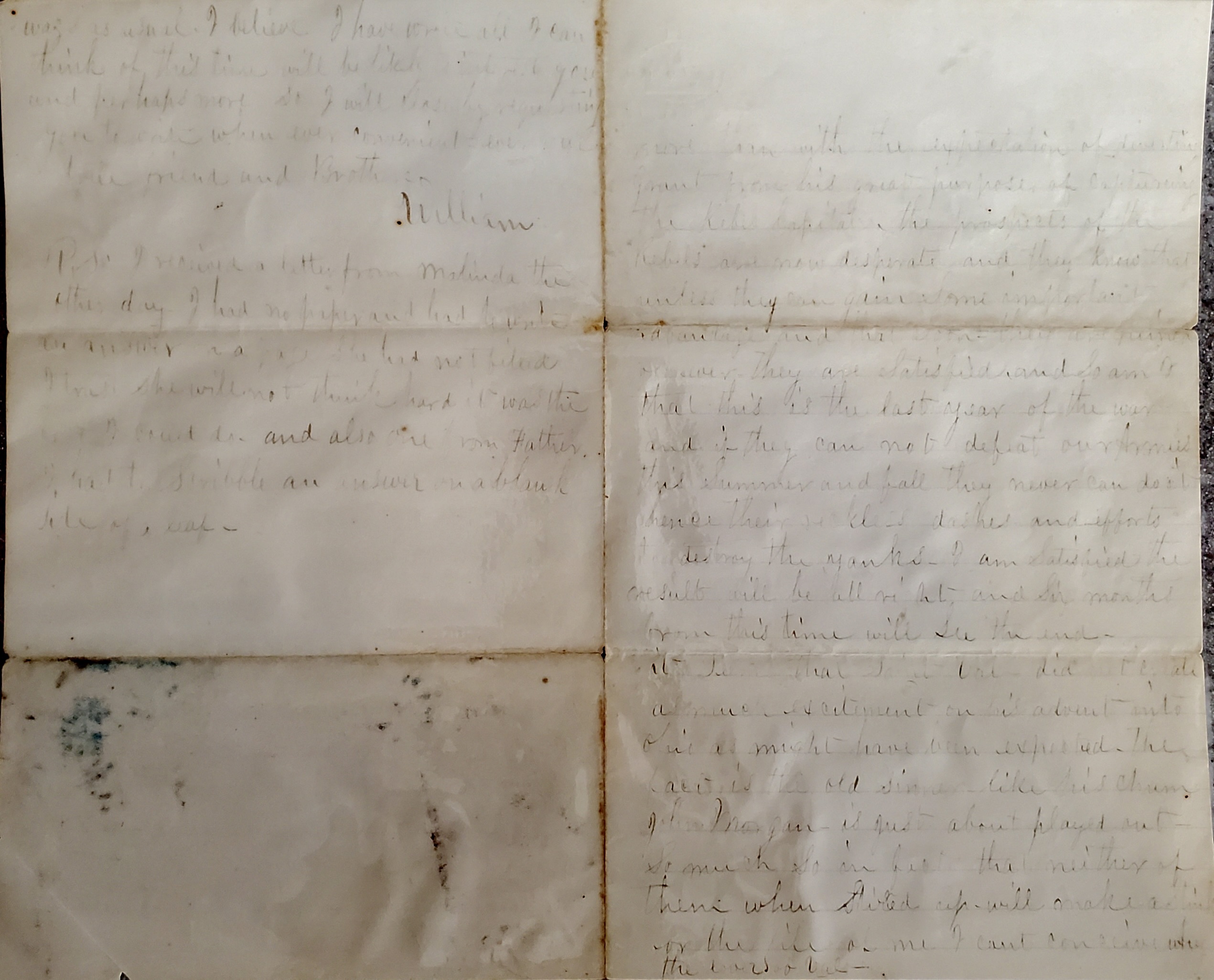

Letter 5

Camp in Sight of Atlanta, Georgia

July 14, 1864

In answer to your kind favor of 26 June that came to hand over a week ago, I write you a line this afternoon. My health is tolerable. Arly is well and hearty. I hope that this will find yourself and little ones well. The lack of something on which to write is the reason I haven’t answered your letter before but Rachel sent us a lot of paper and envelopes so that I can no longer plead that as an excuse. I am glad that something has put an end to your pouting and straightened your face once more. Sorry that the only means that can accomplish that desirable end is likely to do a great deal of damage to the growing crops in Ohio. I do hope that during the continuance of the hot and sultry weather that the process of sweltering and sweating may so work on your constitution that you many at the first good rain that falls like other folks be enabled to rejoice at the prospect of plenty to eat, and not fall away again into your old habit of pouting while everybody else are in good humor.

Joking aside, if the heat at home has been anything like as great as it has here, I pity you and you have the heartfelt thanks of the soldiers for the sympathy you express for us, for this is truly an awful place. This is hardly any cleared land in this whole region of country. It is one everlasting jungle of black jack scrub pines, green briars, thorns and all other kinds of bushes that ever was thought of, and a great many that never was thought of, I believe, all growing in one eternal jumble, and so thick almost everywhere that a bird can’t fly through. Add to all this the face of the earth which contains nary level foot so far as I have yet been in the delectable state of Georgia. But it’s broken up into holes, knolls, three cornered ridges, little knobs, ravines, and gullies—the sides so steep while chasing the Johnnies the first thing we know, sometimes we are at the bottom of them and have to look straight up to see out. It seems as though long ago some internal convulsion of the earth tossed this country from someplace down below, and it don’t seem to have to got used to the change yet. But everything seems out of place and out of shape. Even the stones don’t seem to have yet become accustomed [to] the situation for in the place of occupying a horizontal position like rocks in a civilized country, they stand on end on the corners, the edges, and every imaginable way.

You can form some faint idea from this the difficulties this army has to encounter aside from Johnston’s army on the advance on Atlanta. Our progress thus far has been at times slow, but has been all the time onward until the present time. We have them drove across the Chattahoochee [river] and into the last ditch between the yank and the town. This river is about as wide as the Scioto [river] but deeper. Nearly all of our army except the 14th and 20th [Army] Corps and some cavalry are on the Atlanta side and are now beginning to crowd the Johnnies’ works pretty heavy. Day before yesterday, our Calvary attacked the Rebels cavalry on Cedar Mountain, seven miles east of Atlanta. The extreme right of their lines defeated and drove them off and still holds the mountain. This gives us a position that will eventually force the evacuation of the town or coop the Rebs up in their works which I do not think they will permit as long as there is a chance for them to get away.

Our corps is still encamped on the heights a mile and a half from the river in full view of the steeples and a few houses in Atlanta which as the bird flies is 2 miles, but by the railroad, 8 miles. I think by the 15th of August we will be in town, and by the 1st of September, Grant will have Richmond. This is my private opinion, publicly expressed. From accounts, the Johnnies are stirring them up tolerably lively in Maryland. It will not amount to much in my opinion. It is a raid to obtain supplies more than with the expectation of diverting Grant from his great purpose of capturing the Rebel Capitol. The prospects of the Rebels are now desperate and they know that unless they can gain some important advantage, and that soon, they are ruined forever. They are satisfied and so am I that this is the last year of the war and if they cannot defeat our armies this summer and fall, they never can do it. Hence their reckless dashes and efforts to destroy the yanks. I am satisfied the result will be alright and six months from this time will see the end.

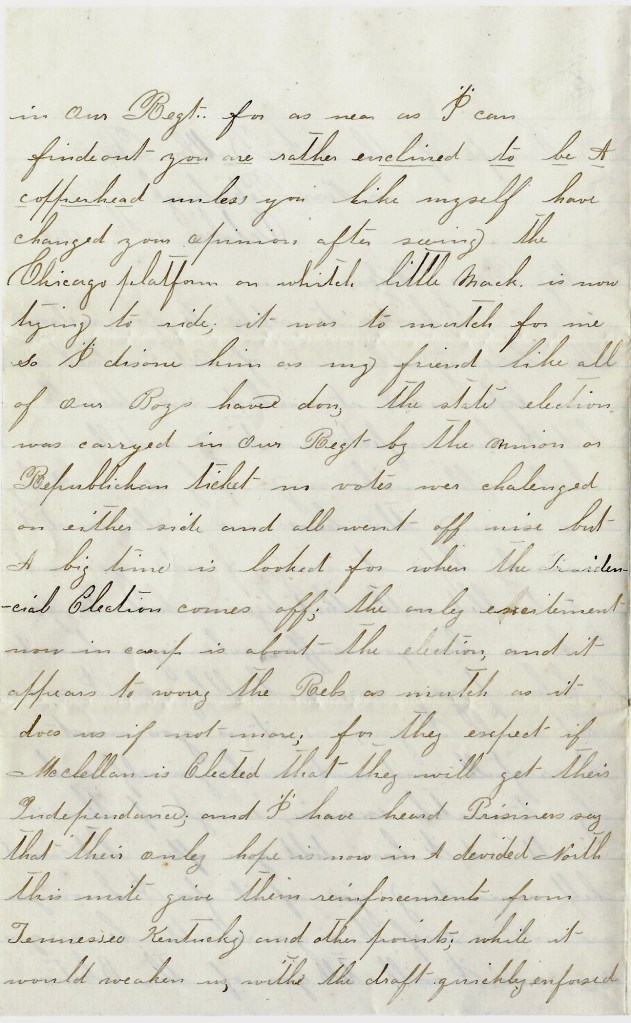

It seems that Saint Val [Clement Vallandigham] did not create as much excitement on his advent into Ohio as might have been expected. The fact is the old sinner, like his chum John Morgan, is just about played out. So much so in fact that neither of them when stirred up will make a stink. For the life of me, I can’t conceive why the lovers of Val should get sick over anything that McClellan could say because there is as little similarity between them as there is between day and night. McClellan is just as upright, honest, and patriotic as they are sneaking, traitorous, and contemptible. Since it is out of the question for the general to be their man for President, yet one consolation remains to them. There is yet balm in Gilead. Frémont still lives and as the abolition butternuts have already taken him to their immaculate bosoms and roll him as a sweet morsel under their tongues, take my word for it, that the Val-ites will do the same, and the postponement of the Chicago [Democratic] Convention is more than presumptive evidence of this fact and that long before the Presidential election, they will be cheek by jowl with the sneaking abolitionists that they have heretofore cursed so much as the cause of the war and all that.

Some may hardly believe this, but I will bet anyone six bits that the peace nuts will hold no convention to nominate a candidate for this election at all, but will all turn a back summer set over the fence and their coats at the same time, and go their death on the pathfinder.

A word or two from the other side and we are done. The Union Convention at Baltimore seen fit in their great wisdom—or more likely the want of it—-to nominate old Abe for another term. He is a bitter pill, you may well believe, for me to take. But as a rational being, of two evils I am bound to take the least and vote for him in preference to Frémont. The nomination for Vice President suits me better. Andy Johnson, I believe, to be one of the best men in the country. He is honest, capable, and better than all, attends to his own business which is more than can be said of Uncle Abe. This will do on politics for a while I think.

The weather here is awful hot. All we have done for a week is cook and eat and try to keep cool. Our pup tents are literally hid in brush sheds over them and brush set up around them. A storm last night mixed matters somewhat and tumbled over the main house. But everything is now in order and time wags as usual. I believe I have wrote all I can think of this time [that] will be likely to interest you, and perhaps more. So I will close by requesting you to write whenever convenient. Ever your true friend and brother. — William

P. S. I received a letter from Malinda the other day. I had no paper, and had to write an answer on a page she had not filled. I trust she will not think hard. It was the best I could do, and also one from father. I had to scribble an answer on a blank side of a leaf.

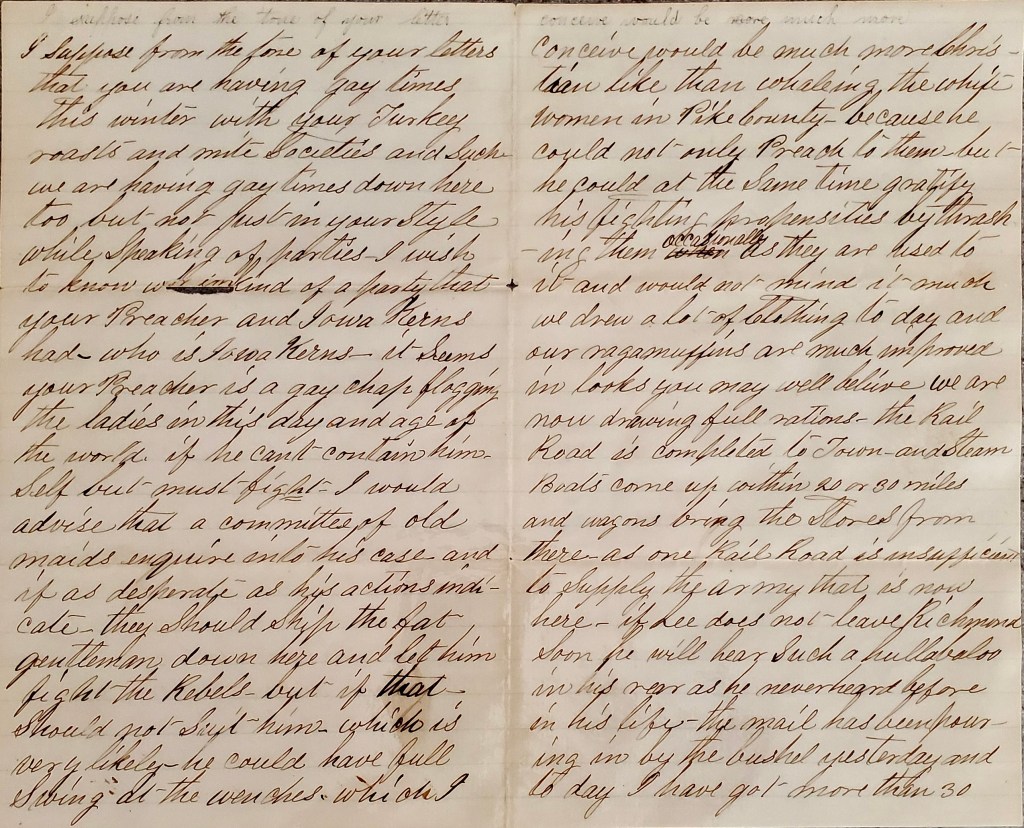

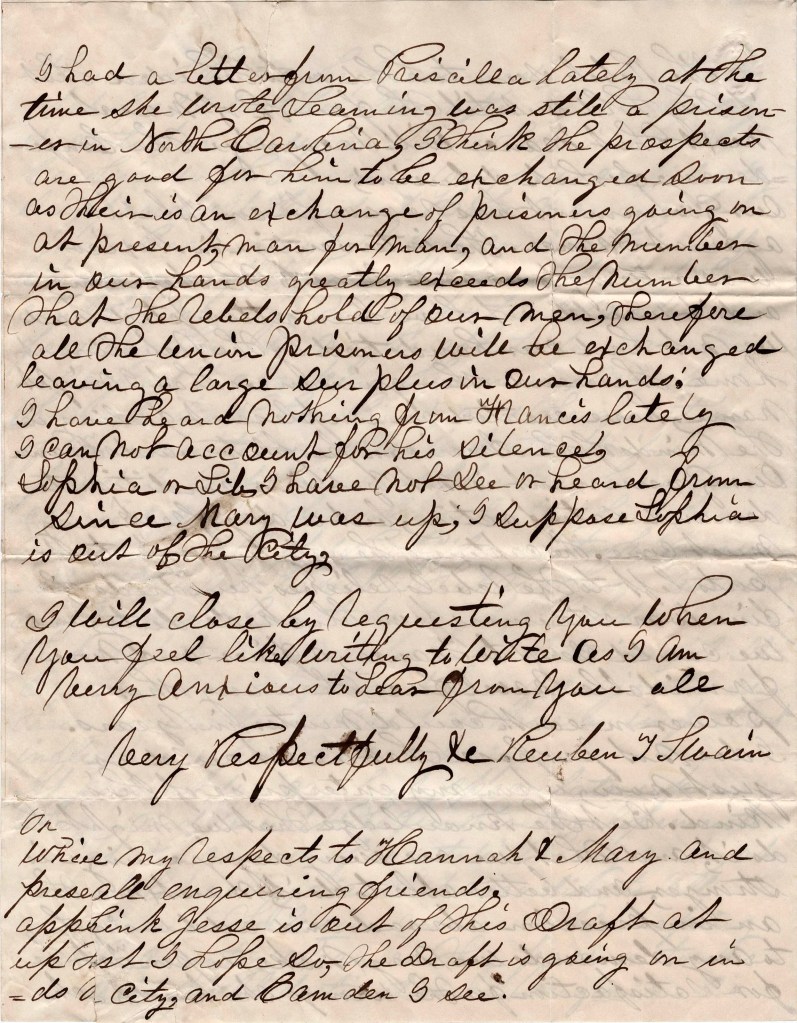

Letter 6

Goldsboro, North Carolina

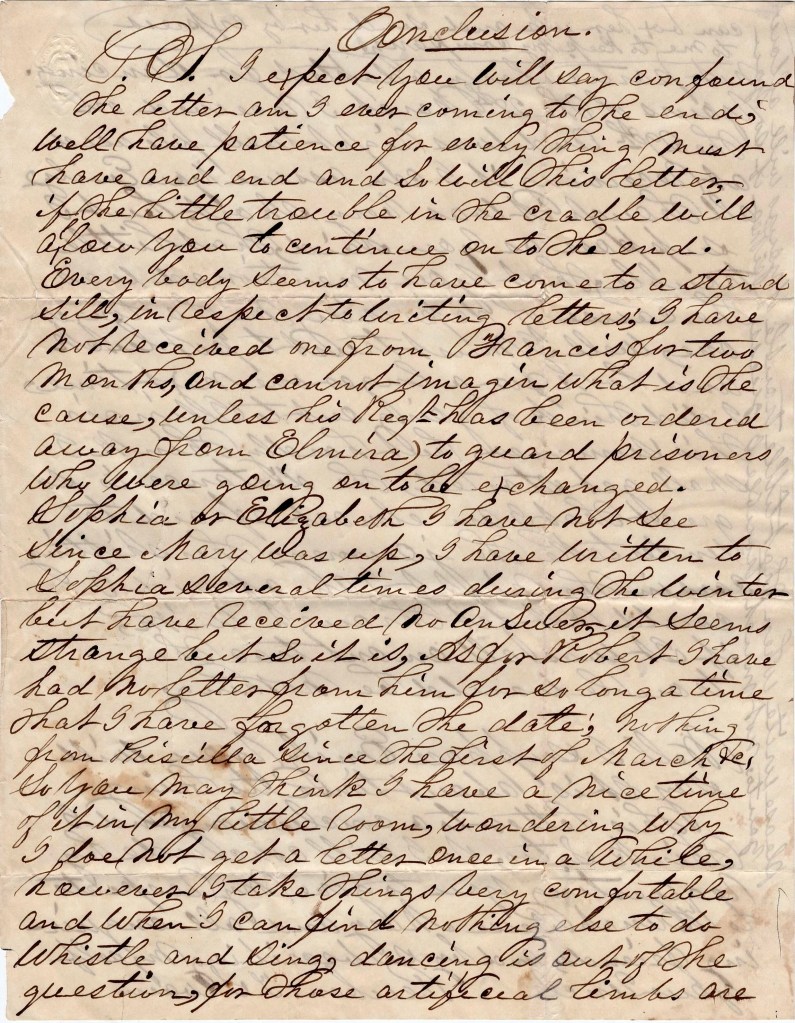

March 27, 1865

Dear Sena,

I received a couple of letters from you yesterday and you complain that I don’t answer your letters. I have this to say on the subject. If you was in my place, you would I think write as little as I do, if not less. It was nearly two months that we had no communication whatever with God’s country. This I think will be sufficient to explain to you the reason you have had no letters. It is not because I am out of humor with you al all, but simply for the want of an opportunity to write.

We are now in camp but I am so busy making out my returns that I can’t write much so you must be satisfied with short letters for a while at least. I suppose from the tone of your letters that you are having gay times this winter with your turkey roasts and mighty societies and such. We are having gay times down here too but not just in your style. While speaking of parties, I wish to know what kind of party that your preacher and Iowa Kerns had. Who is Iowa Kerns? It seems your preacher is a gay chap, flogging the ladies in this day and age of the world. If he can’t contain himself but must fight, I would advise that a committee of old maids enquire into his case and if as deperate as his actions indicate, theyshould ship the fat gentleman down here and let him fight the Rebels. But if that should not suit him—which is very likely—he could have full swing at the wenches which I conceive would be much more Christian like than whaling the white women in Pike county—because he could not only preach to them but he could at te same time gratify his fighting propensities by thrashing them occasionally as they are used to it and would not mind it much.

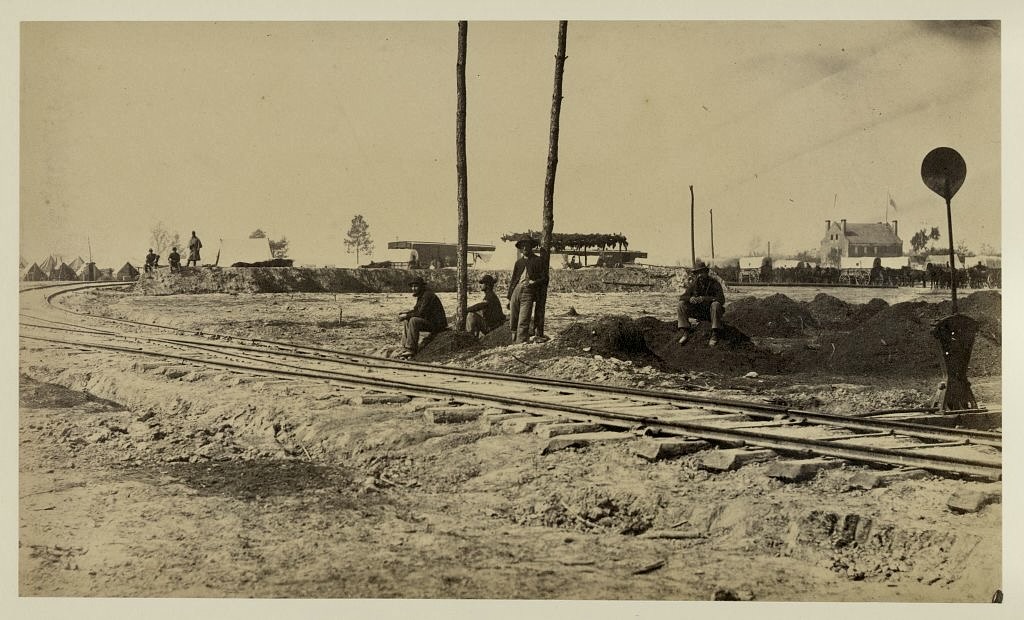

We drew a lot of clothing today and our ragamuffins are much improved in looks, you may well believe. We are now drawing full rations. The railroad is completed to town and steamboats come up within 20 or 30 miles and wagons bring the stores from there. As one railroad is insufficient to supply the army that is now here, if Lee does not leave Richmond soon, he will hear such a hullabaloo in his rear as he never heard before in his life.

The mail has been pouring in by the bushel. Yesterday and today I have got more than 30 letters, a nice coat vest, socks, and shirts, and a nice cake of butter. You ought to have seen me wade into it. It come just as my cook took a warm corn pone out of the oven. Oh but it was good.

Maj. Hinson says the young lady didn’t ask for a man to guard her bull. He says someone is likely to be slandered but he hasn’t come to a conclusion yet whether it will be him or the bull. This is all this time. Write often all the gossip going on in the neighborhood. No more but I am ever your affectionate brother, — William