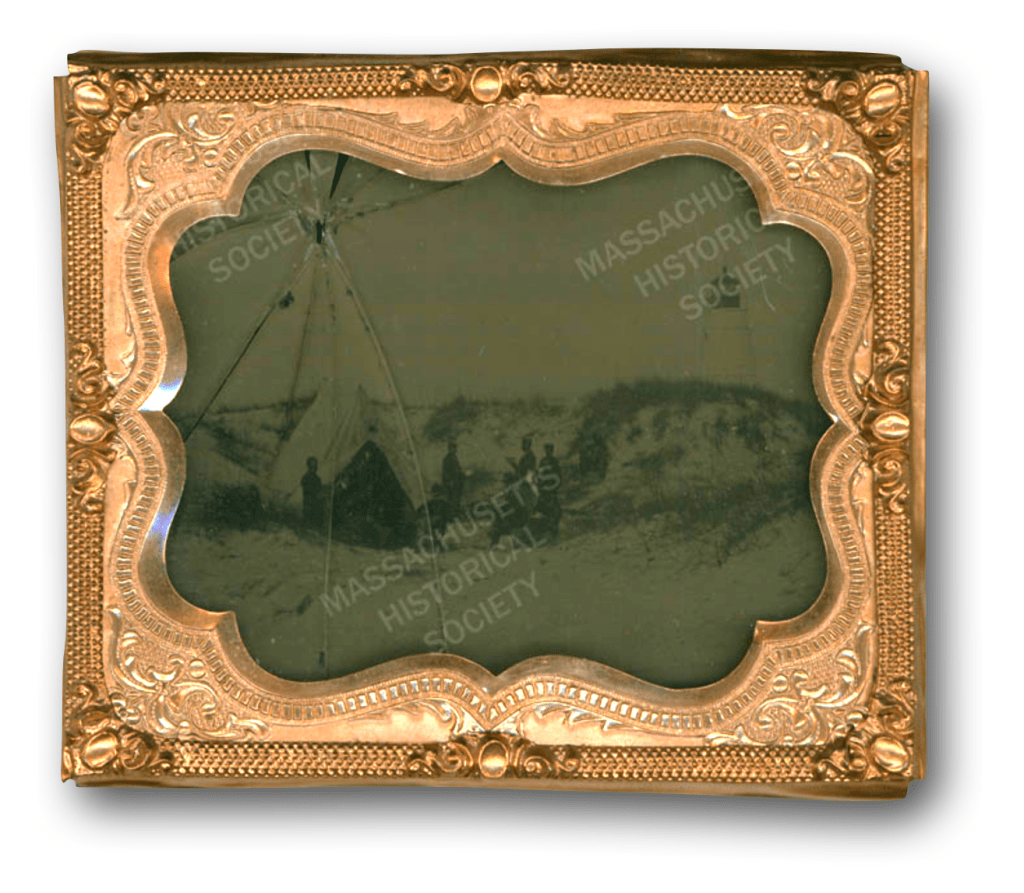

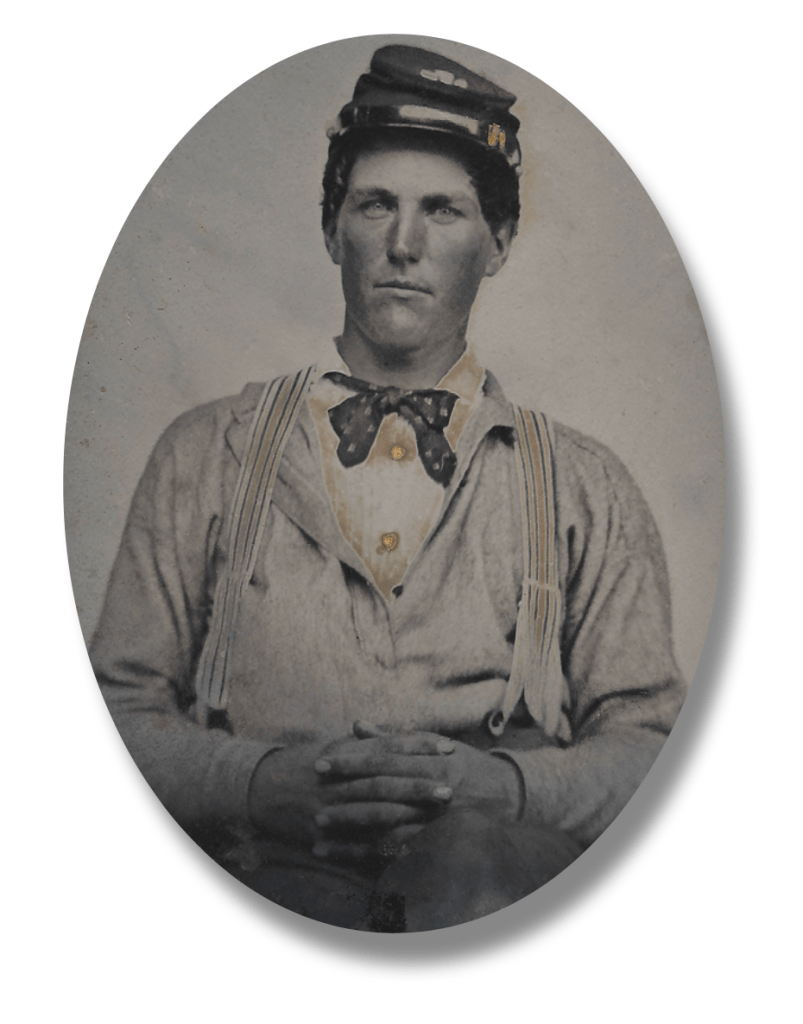

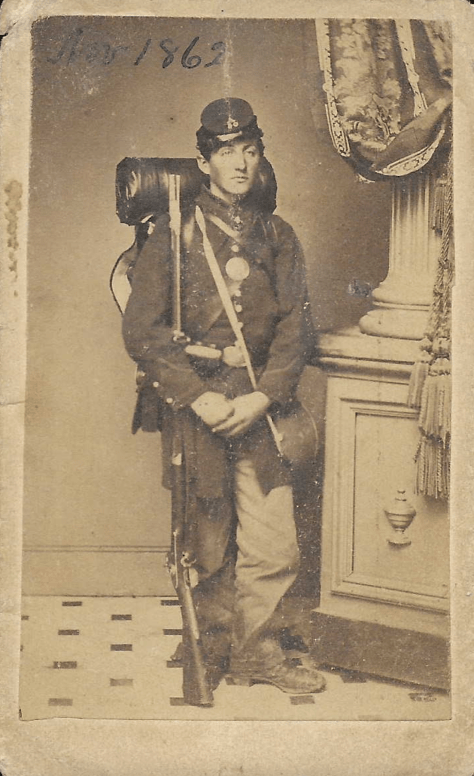

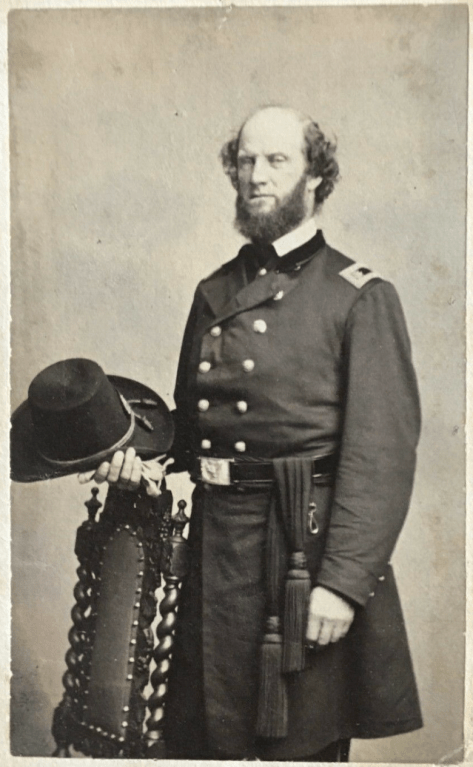

The following letters were written by George Newell Boynton (1846-1863), the son of George Washington Boynton (1820-1877) and Abby N. Stocker (1819-1898) of Georgetown, Essex county, Massachusetts. George was only 16 years old when he enlisted on 16 August 1862 as a private in Co. K, 50th Massachusetts Infantry. He died of disease at Baton Rouge on 3 July 1863. Burial records of the Harmony Cemetery in his hometown inform us that George’s body was exhumed in Louisiana by his father and returned to Georgetown along with those of Richmond D. Merrill (died 28 June 1863) and Amos Spofford (died 4 June 1863), all three in Co. K, 50th Massachusetts.

Despite the high mortality rate, I have transcribed a considerable number of letters by members of the 50th Massachusetts Infantry to date. They include:

William G. Hammond, Co. A, 50th Massachusetts (1 Letter)

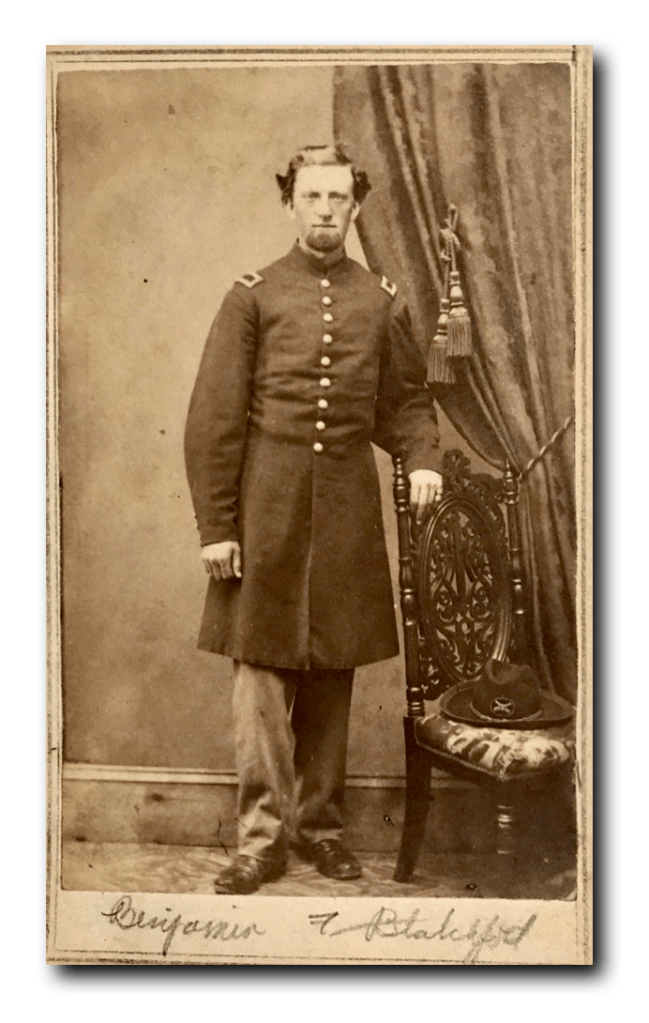

Benjamin F. Blatchford, Co. B, 50th Massachusetts (5 Letters)

Rufus Melvin Graham, Co. F, 50th Massachusetts (29 Letters)

Jackson Haynes, Co. F. 50th Massachusetts (1 Letter)

William Rockwell Clough, Co. G, 50th Massachusetts (5 Letters)

Benjamin Austin Merrill, Co. K, 50th Massachusetts (5 Letters)

Moses Edward Tenney, Co. K, 50th Massachusetts (1 Letter)

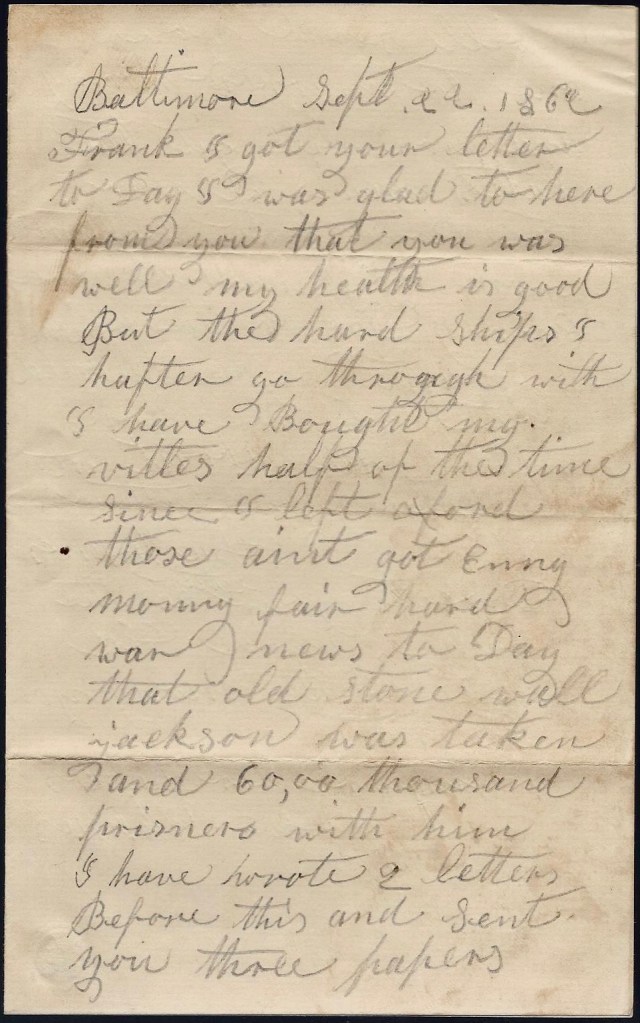

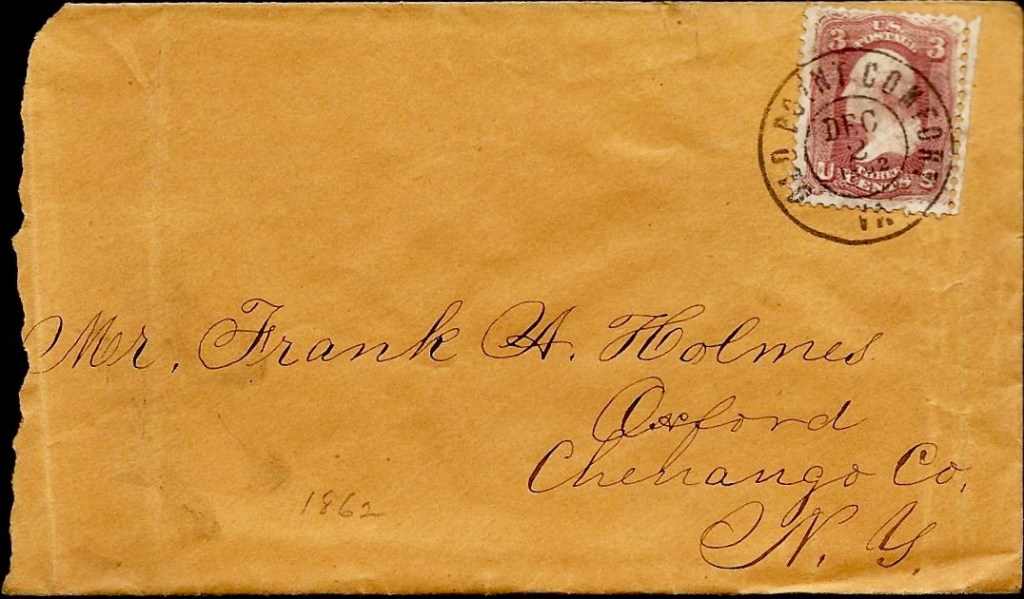

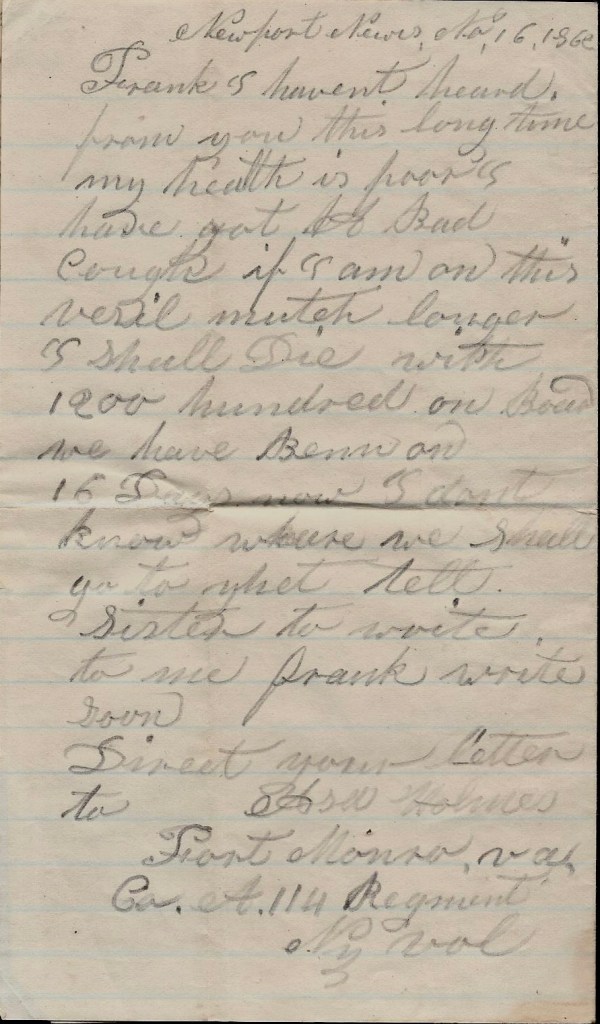

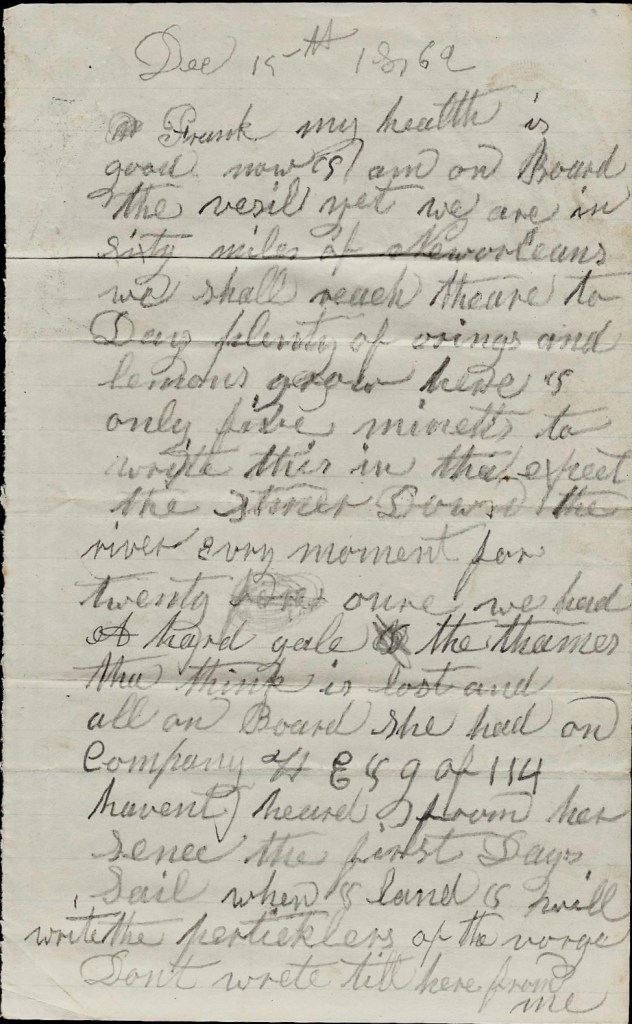

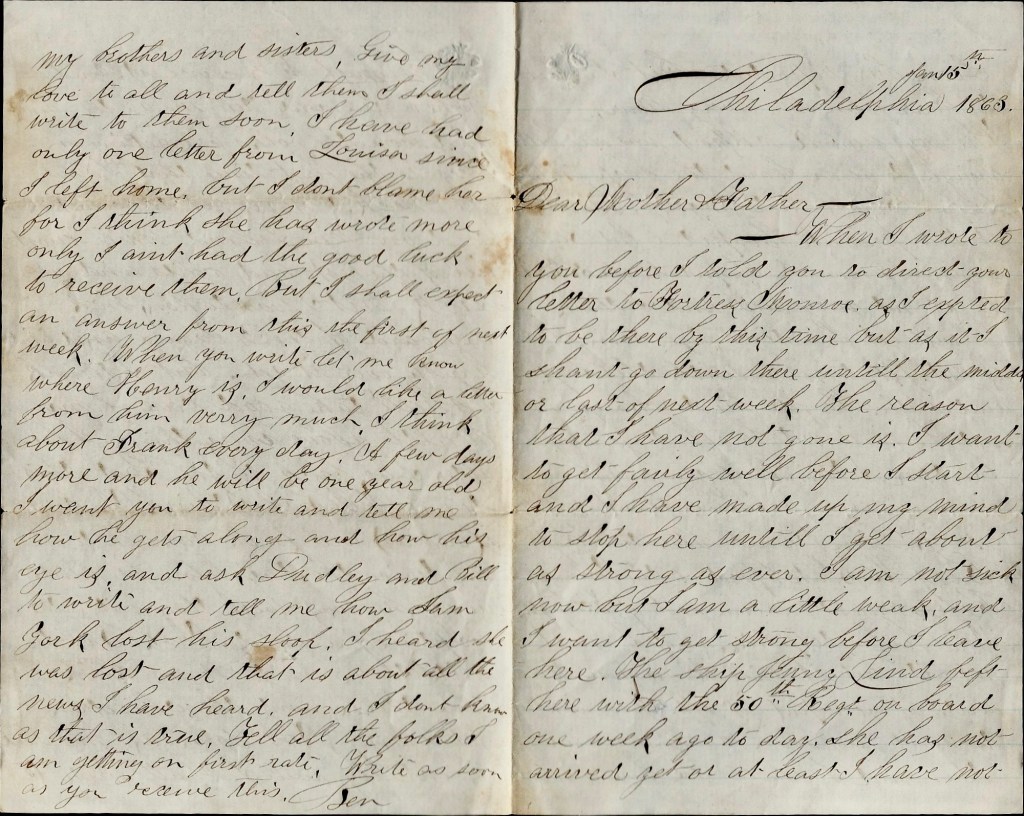

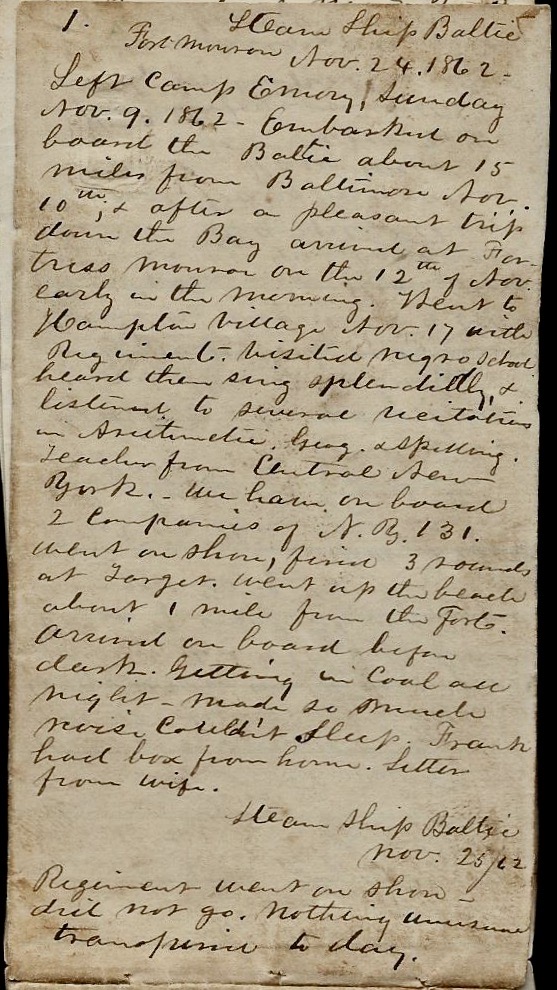

Letter 1

New York City

November 21, 1862

Dear Father,

I arrived here yesterday morning at 9 o’clock after having a rough passage. I has rained ever since we left Camp Stanton and is raining now and the Boys are all scattered over the city and are now jumping out of the windows and every other place. We started from Boston about 3 o’clock, arrived in Worcester about 7 o’clock and stopped about a half an hour and then we started for Norwich, Ct., and arrived there about 12 o’clock at night. Then we took the boat and piled in four deep. Some were sound asleep, others dancing and raising a ruckus. After we had been on board about an hour, I went up on deck to report for guard duty and stopped up there all night and finally we came in sight of New York City and landed and came into line, marched up Broadway about a mile, and stopped at Park Barracks in front of City Hall until 4 o’clock. And next we marched into an old stone house now used as barracks. It is the place where Billy Wilson’s regiment stopped. The Orderly is round after the letters and I must draw mine to a close. I am well, fat & saucy. Give my respects to all the folks but [illegible]

P. S. Tell mother that her Chicken Pie went good.

Don’t write until you hear from me again for I can’t tell where to direct it.

Yours, — G. N. Boynton

Letter 2

New York [City]

December 8 [1862]

Dear Father,

Having a few spare moments I thought I would write you a few lines to let you know that we are a going to embark today on the Propellor Jersey City for Fortress Monroe. I got that box that mother and Mrs. Pickett sent last Thursday. Tell Mrs. Pickett that Frank has lost his knapsack and all his clothes. I have got my vest and it fits me first rate and I am very much obliged to you for it.

By the way, I have enjoyed myself first rate. I have been to Barnum’s Museum and Niblo’s Garden 1 and heard Ed[win] Forrest play and it was splendid. Last Monday I went up to Central Park and was was magnificent.

I must dry up for the orders are to fall in and be ready in five minutes. Yours, — G. N. B.

P. S. This makes 4 letters that I have wrote and I haven’t received only two.

1 Niblo’s Garden was a theater on Broadway and Crosby Street. At the time, Edwin Forrest was performing in either Metamora or “The Broker of Bogota” depending on the evening George attended.

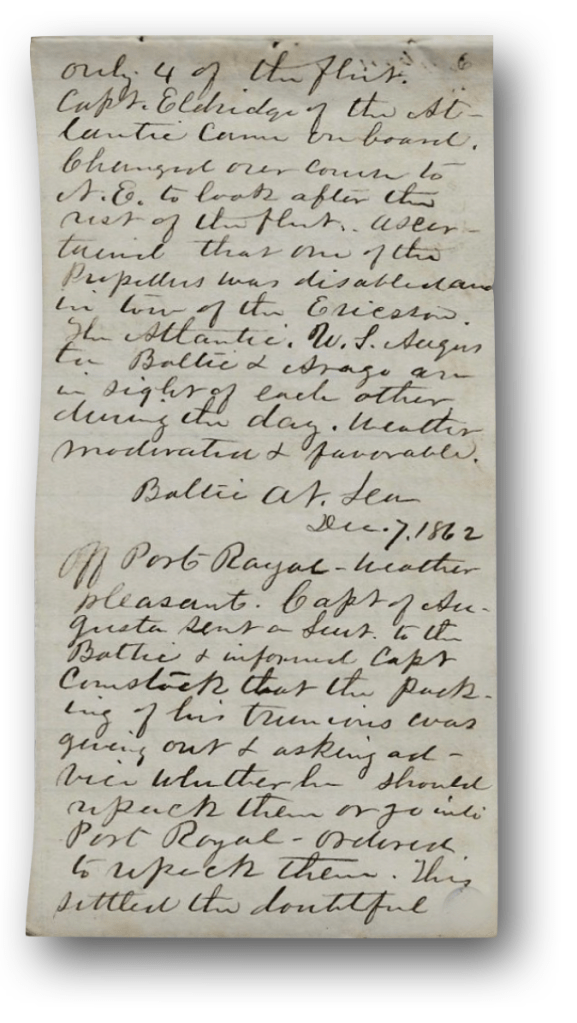

Letter 3

On board the Barque Guerrilla

January 18 [1863]

Dear Father,

Having some spare time, I thought that I would write you a few lines to let you know that I am in good health and I hope that you are the same. We left Hilton Head January 1st and arrived at Ship Island on the 15th and stopped there three days and we are now on our way up the Mississippi to New Orleans. I have had a pretty good time since I left Camp Stanton and I have seen a good many sights. While we was at Hilton Head, I saw George Hunkins, Ed Hazen, and Dennis Adams [of 1st Massachusetts Cavalry]. George Hunkins is awful sick of the army, I tell you.

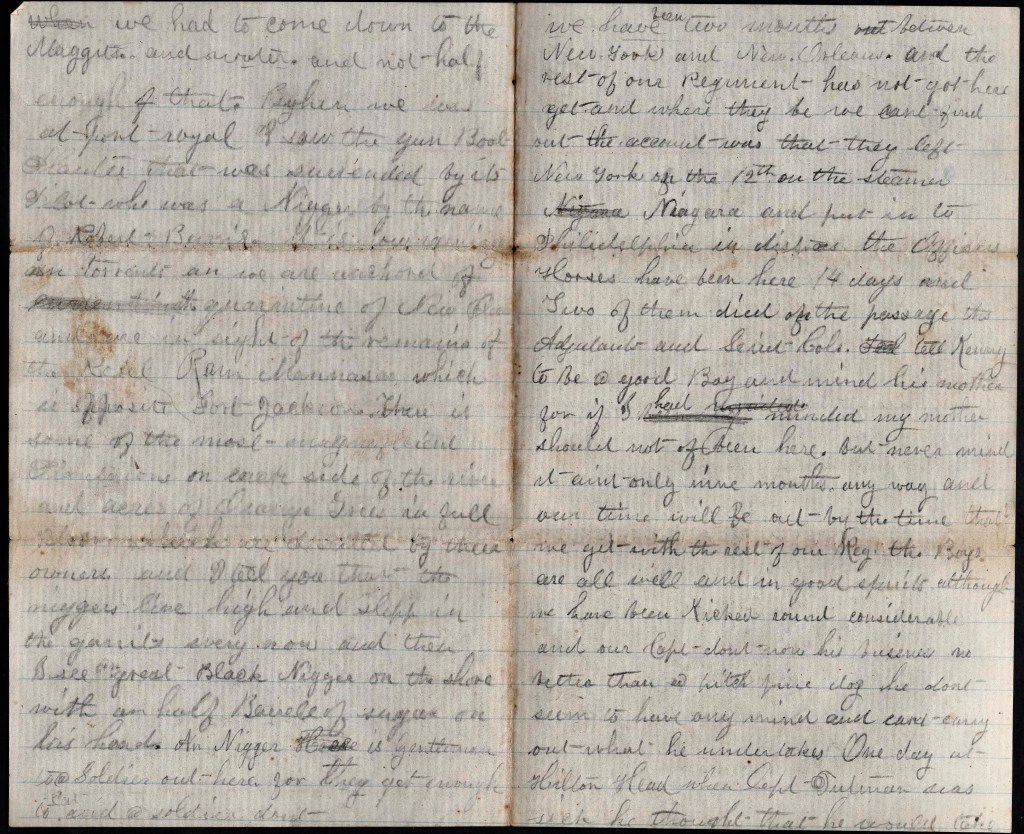

Since we left Hilton Head I have had nothing to eat but hard bread with maggots and salt horse and a quart of water. I tell you it makes me think of home—especially when we had to come down to the maggots and water, and not half enough of that. When we was at Port Royal, I saw the gunboat Planter that was surrendered by its pilot who was a Nigger by the name of Robert Smalls.

It is now raining in torrents and we are anchored off Quarantine of New Orleans in sight of the remains of the Rebel Ram Manassas which is opposite Fort Jackson. There is some of the most magnificent plantations on each side of the river and acres of orange trees in full bloom which are [ ] by their owners. And I tell you that the niggers live high and sleep in the garrets every now and then. I seen a great Black Nigger on the shore with a half barrel of sugar on his head. A Nigger is gentleman to a soldier out here for they get enough to. east and a soldier don’t.

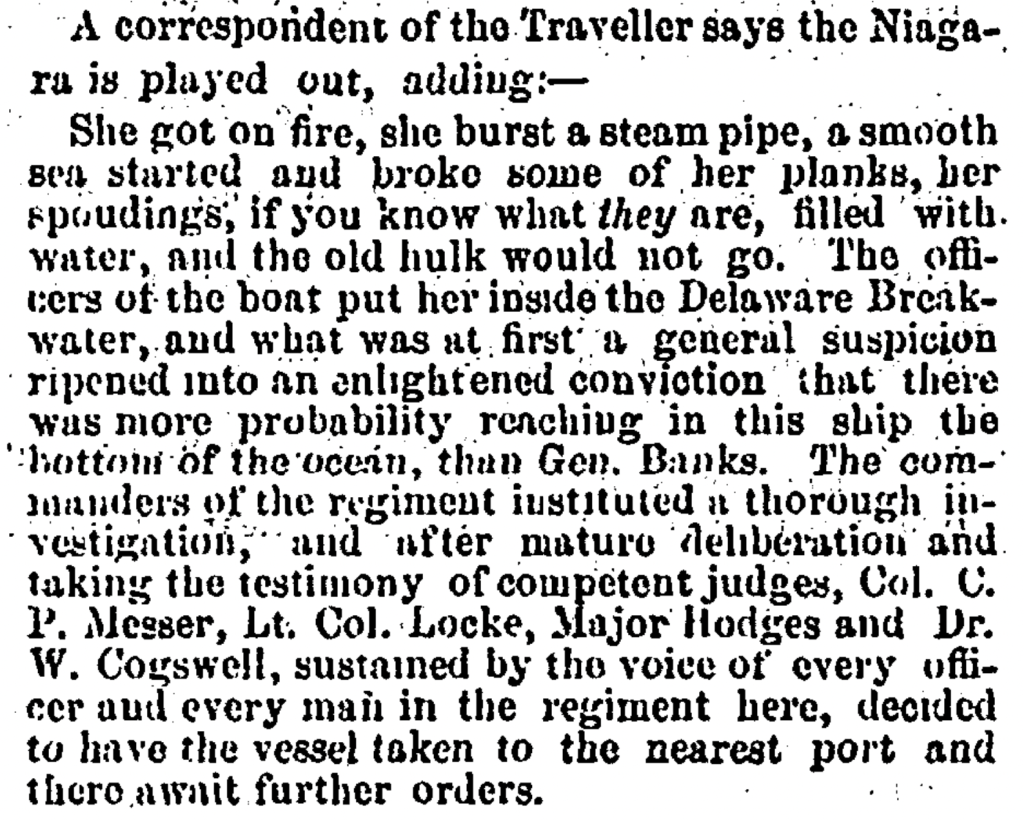

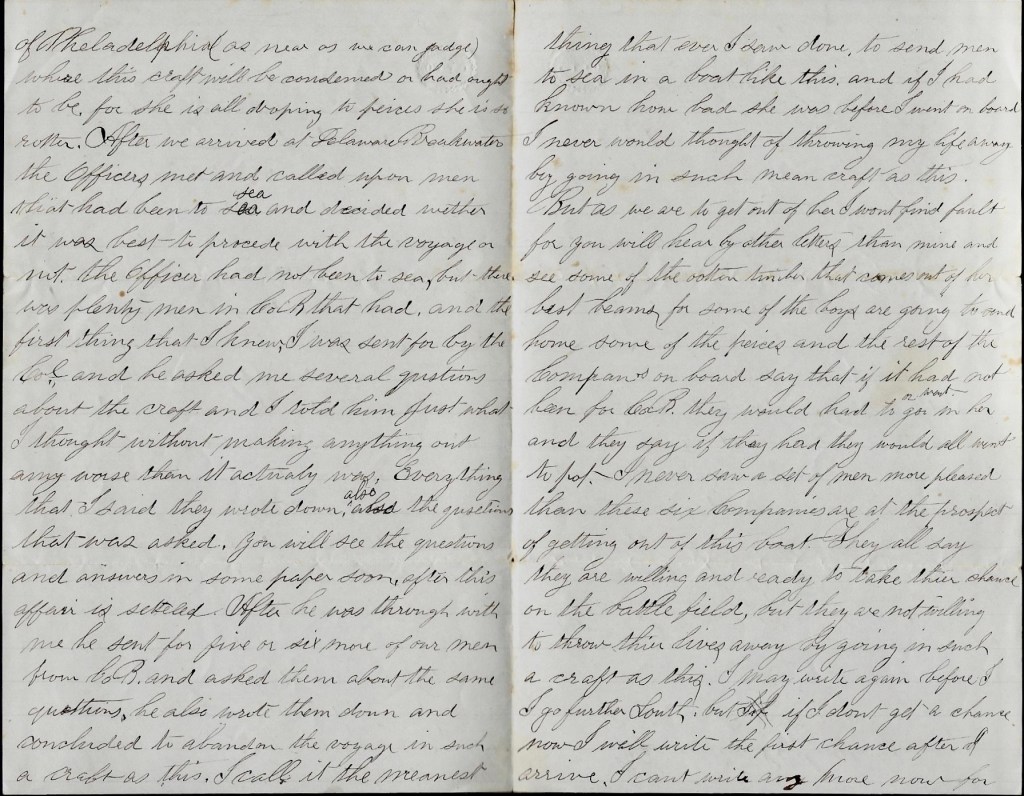

We have been two months between New York and New Orleans and the rest of the regiment has not got here yet and where they be, we can’t find out. The account was that they left New York on the 12th on the steamer Niagara and put in to Philadelphia in distress. The oficers’ horses have been here 14 days and two of them died on the passage—the Adjutant’s and Lieutenant-Colonel’s.

Tell Kenny to be a good boy and mind his mother for if I had minded my mother, should not of been here. But never mind. It ain’t only nine months anyway and our time will be out by the time that we get with the rest of our regiment. The Boys are all well and in good spirits although we have been kicked round considerable and our Captain [John G. Barnes] don’t know his business no better than a pitch pine dog. He don’t seem to have any mind and can’t carry out what he undertakes. One day at Hilton Head when Capt. [George D.] Putnam [of Co. A] was sick, he thought that he would take us out on Battalion Drill and he could not form us in a hollow square and it tickled the Boys, I tell you, for he thinks he [is] capable of bring a Brig. General. We have got orders [to] leave here for Carrollton which is six miles above New Orleans.

They do their teaming here with four mules. The driver rides the right ordered mule and drives with one reign which is attached to nigh leader. 1

Some evil-minded whelp stole my writing base at Hilton Head and I borrowed this. I wrote one letter while I was at Hilton Head. I have just received a letter from you stating that [you] did not receive any word [from] me and that you sent me some money by Charles Tenney. The rest of the regiment has not arrived here yet. It is about dinner time and I guess that I will dry up now so goodbye. Yours, — George N. Boynton

1 Four-mule teams, driven by a rider on one of the mules, were common in the South, particularly for transporting supplies and equipment. Mules were preferred over horses due to their strength, stamina, and ability to navigate difficult terrain. The driver, known as a mule skinner, would ride the lead mule and guide the team using a single rein and voice commands.

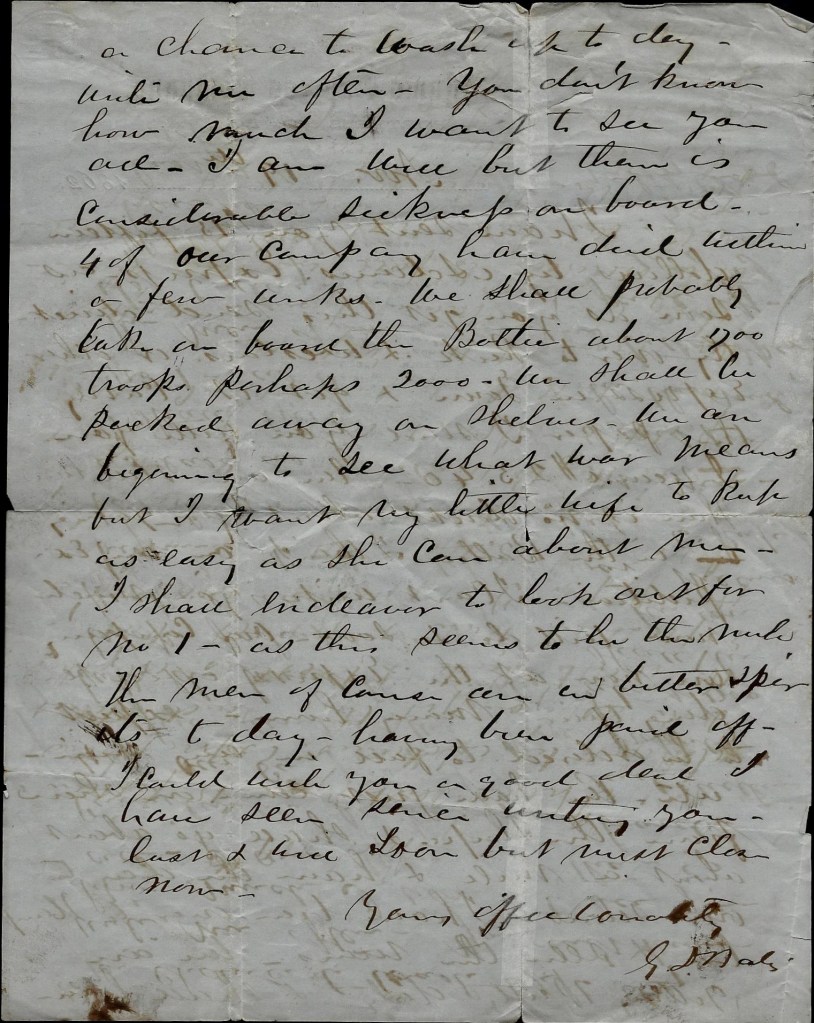

Letter 4

Camp Parapet

Carrollton, Louisiana

January 23rd 1863

Dear Father,

I received a letter from mother this morning dated January 5th stating that she had not received any letter from me since I left Mew York and I did not know hardly what to make of it for I have wrote four letters since we left New York.

We are encamped 8 miles above New Orleans to a place by the name of Carrollton on the banks of the Mississippi River and I am enjoying myself first rate. I have been to work all day making a floor to our tent and it is as warm here as it is in Massachusetts in June. You spoke about giving my love to Mr. F in your letter. He has not got here yet nor he ain’t likely to get here for a month.

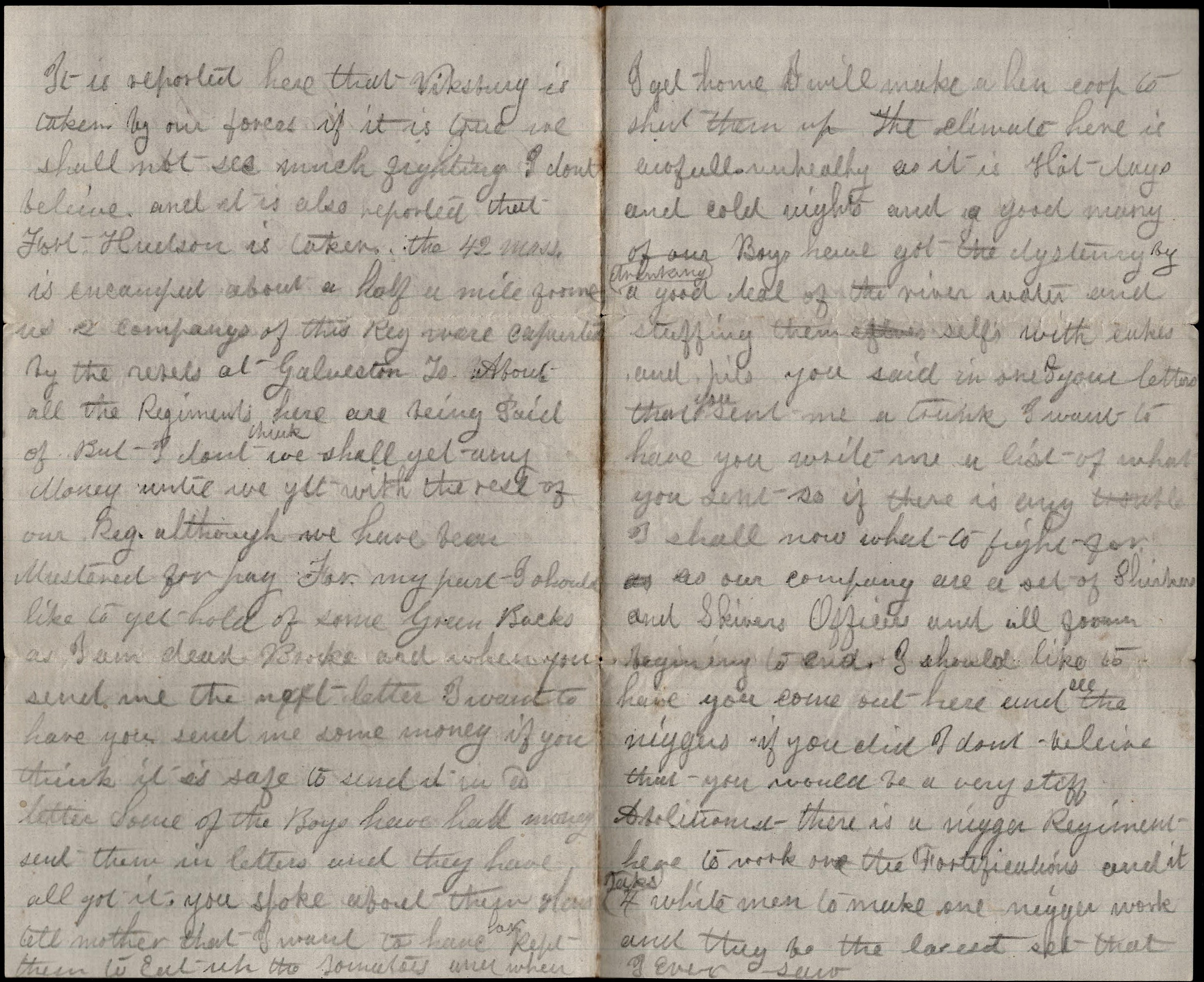

It is reported here that Vicksburg is taken by our forces. If it is true, we shall not see much fighting, I don’t believe. And it is also reported that Port Hudson is taken.

The 42nd Massachusetts is encamped about a galf a mile from us. A company of this regiment were captured by the Rebels at Galveston Texas. About all the regiments here are being paid off but I don’t think we shall get any money until we get with the rest of our regiment although we hsave been mustered for pay. For my part, I shoiuld like to get hold of some green backs as I am dead broke and when you send me the next letter, I want you to send me some money if you think it is safe to send it in a letter. Some of the Boys have had money sent them in letters and they have all got it.

“…Our company are a set of shirkers and skinners—officers and all from beginning to end.”

— George N. Boynton, Co. K, 50th Massachusetts Infantry

You spoke about them hens. Tell mother that I want to have her kept them to eat up the tomatoes and when I get home I will make a hen coop to shut them up. The climate here is awful unhealthy as it is hot days and cold nights and a good many of our Boys have got the dysentery by drinking a good deal of the river water and stuffing themselves with cakes and pies. You said in one of your letters that you sent me a trunk. I want to have you write me a list of what you. sent so if there is any trouble, I shall know what to fight for as our company are a set of shirkers and skinners—officers and all from beginning to end.

I should like to have you come out here and see the niggers. If you did, I don’t believe that you would be a very stiff Abolitionist. There is a nigger regiment here to work on the fortifications and it takes four white men to make one nigger work and they he the laziest set that I ever saw. 1

We have just heard from the rest of our regiment. They left Philadelphia on the 5th of January. I guess that I will dry up as it is about time for roll call. you must [excuse] this writing as it is the best that I can do, but I guess that you can pick it out. I am well and I have not been sick a day since I left Boxford. From your son, — George N. Boynton

P. S. Tell Jericho not to let Old Hutch lick him.

1 The Black regiment must have been members of the 1st Louisiana Native Guards.

Letter 5

Baton Rouge

February 21st 1863

Dear Parents,

I received a letter from you this morning dated February 2nd and was glad. to hear from you. We are encamped in the City of Baton Rouge close to the Louisiana State Prison. We are in Gen. Dudley’s [3rd] Brigade [of the 1st Division] with the 30th Massachusetts, 174th and 61st New York and 2nd Louisiana. Daniel R. Kenny is a Captain [of Co. C] in the 2nd Louisiana. I suppose that you. know him. I believe that you took a watch from him two or three times for board bills. About all of the Boys have been sick with the dysentery and diarrhea but I have been well so far. Frank Pickett is sick and in the hospital, Three companies of our regiment arrived here last Saturday and all the officers except the Lieutenant-Colonel [John. W. Locke].

All I got out of that stuff that you sent was a pound of tobacco and a towel and one letter. But no money. We have been paid off and I sent $30 to you. by Adams Express. We have a pretty hard time here for our General is a Tiger. He gives us a Brigade Drill of four hours every afternoon and go on guard every other day. I have just got in from picket guard. It is fun, I tell you, but rather hard work—especially marching out and coming in. 1

When I was at Carrollton, I saw a lieutenant that was at Robert Boyes’ last summer from N. H. He is overseer on a sugar plantation.

I suppose that Father has as much as he can tend to this winter collecting taxes and sheriffing and is as cross sometimes as usual but if I was at home I should not mind it but I expect that when I get home it will become, “George, it is 9 o’clock, go to bed.” But I guess that I shall be glad to get into a good bed.

Capt. [John G.] Barnes is about played out with the dysentery and I should not winder if he had to come home on account of it. It is reported that our Brigade is a going to stay here in the city. The 40th and 49th Massachusetts came here about a week ago and I found a good many Boys that I am acquainted with. One of them is John Holley. He is a corporal in Co. D. He looks as rugged as a bear. Tell Kenny to be a good boy for brother George is a coming home next June.

When I was on picket about a week ago, I and a fellow in Co. I fired at a Rebel cavalryman but he was a little too smart for us. But finally [James M] Magee’s Cavalry captured him and I [had] the pleasure of seeing the gentleman that I fired at.

It is about time for roll call and I must bring my letter to a close and bid you goodbye. Yours truly, — George N. Boynton

P. S. When you write me a letter, write me a list of what you sent by Charles Tenney. Give my love to Esther and all the rest. Postage stamps are played out with us.

1 In the regimental history published in 1907, the author informs us that “A soldier’s life at Baton Rouge was no holiday. It was one continuous round from sunrise to sunset, with some hours interspersed for rest and recreation, and then occasionally with passes in our pockets, we were allowed to roam about the streets and down to the river, but taken all in all the most agreeable duty was that out the outer reserve or picket guard. The detail, made up about nine a.m. took with them one day’s rations and blankets, and marched out about two miles to relieve the guard of the day, remaining in turn 24 hours, each man being two hours on duty and four hours off…When the weather was pleasant, to go on picket duty seemed a good deal like going on a picnic, the noys frying their rations of pork and potatoes….and making coffee about an open fire, and the enjoyment was made a little keener by occasional glimpses of a rebel vidette making his appearance beyond the lines…”

Letter 6

Baton Rouge

March 2nd 1863

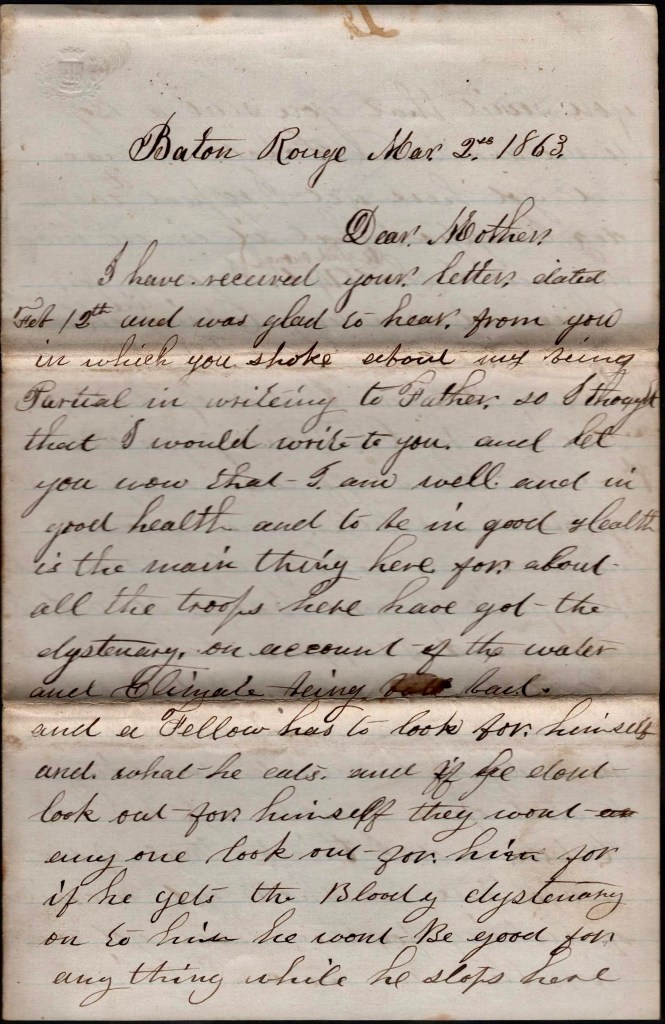

Dear Mother,

I have received your letter dated February 12th and was glad to hear from you in which you spoke about my being partial in writing to Father so I thought that I would write to you and let you know that I am well and in good health—and to be in good health is the main thing here for about all the troops here have got the dysentery on account of the water and climate being bad. A feller has to look out for himself and what he eats and if he don’t look out for himself, they won’t anyone look out for him for if he gets the bloody dysentery on to him, he won’t be good for anything while he stops here.

You said that you sent a box to me and Frank Pickett. It has not got here yet. I expect it every day. I suppose that it is a nice one and I shall be glad enough to get it I guess for I have not seen any cooking like Marms since I left home and I hope that I shall get more of it than I did of that you sent me [by] Charles Tenney for all I got out of that stuff was one pound of tobacco, one letter, and a towel. No money or nothing else. We have been paid off and I sent $30 to you and I suppose that you have got it by this time.

We have had orders to pack our knapsacks and be ready at a minute’s warning to start on a march up to Port Hudson and I think that if we go up there we shall get a devil of a licking for they have got more troops than we have, I think.

I received a letter from Esther and was much pleased to hear from her and I shall write to her tomorrow. I wrote a letter to you and sent it on the 17th. There is not any news here special and it is getting about time for Dress Parade and I must draw my letter to a close and bid you goodbye. Yours truly, — George N. Boynton

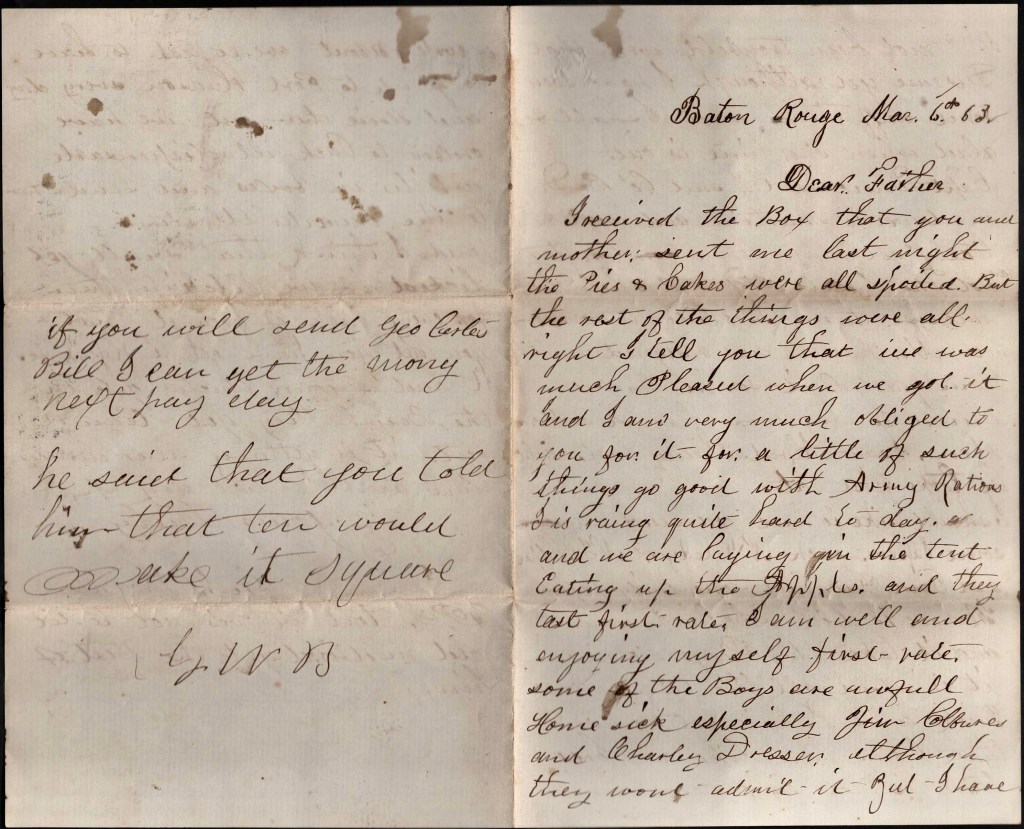

Letter 7

Baton Rouge

March 6th 1863

Dear Father,

I received the box that you and mother send me last night. The pies and cakes were all spoiled but the rest of the things were all. right. I tell you that we was much pleased when we got it and I am very much obliged to you. for it for a little of such things go good with army rations. It is raining quite hard today and we are laying in the tent eating up the apples and they taste first rate. I am well and enjoying myself first rate. Some of the Boys are awful home sick—especially Jim Colburn and Charley Dresser although they won’t admit it but I have not been troubled with that disease yet although I have seen some rough times and I shall be glad when our time is out.

Capt. Duncan’s company and companies B & D are down to [the] quarantine [station] and won’t be likely to get any further [up the Mississippi] for they have got the Small Pox and ship fever amongst them. Mrs. Pickett’s wonderful Mr. [Robert] Hassall [the Chaplain] has resigned and I am glad of it for he don’t amount to any more than a sitting hen. I saw Alfred Cheeny last night. He looks first rate.

I should like to have you send me some papers such as New York Ledger, New York Clipper, and True Flag and some daily papers.

We have to drill very hard now and it takes the Boys down. It is about all the time double quick and I have got so now that I can run like a horse. There is not any news here to write about. We expect to have to go up to Port Hudson every day and drive them out. We have orders to pack all indispensable articles in boxes and send them to the Quartermasters. And I think that we shall get licked if we pitch into them for every inch of ground that you get, you have to fight for it. And if your Uncle gets in the brush, they get cleaned out. It is getting near dinner time and I must dry up. Yours truly, — G. N. Boynton

P. S. Tell Lewis not to let Old Medford get the best of him.

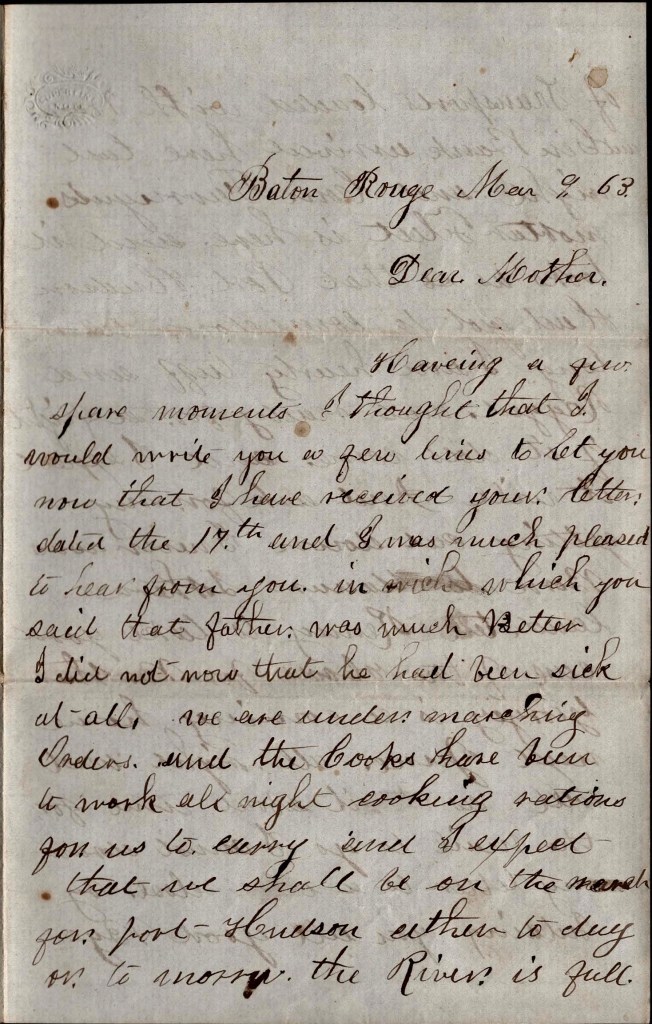

Letter 8

Baton Rouge

March 9, 1863

Dear Mother,

Having a few spare moments I thought that I would write you a few lines to let you know that I have received your letter dated the 17th and I was much pleased to hear from you in which you said that father was much better. I did not know that he had been sick at all.

We are under marching orders and the cooks have been to work all night cooking rations for us to carry and I expect that we shall be on the march for Port Hudson either today or tomorrow. The river is full of transports loaded with troops and Gen. Banks arrived here last night and Commodore Farragut’s mortar fleet is here and it looks [to] us that Port Hudson had got to come down before long.

I am hearty, tough, and rugged and ready for a fight if it does come and I expect it will. And as for my getting cut down, I never was born to manure southern land. Tell Kenny to take good care of the hens for brother Georgey is a coming home next June all right and well. As it’s about time for the mail to go, I must draw my letter to a close by bidding you all goodbye. From your son, — George N. Boynton

P. S. I have wrote to Eben and Esther.

The company that the Hawkes boys are in is down to Quarantine sick with the small pox and ship fever. I saw A. P. Cheney yesterday. He looked as rough as ever.

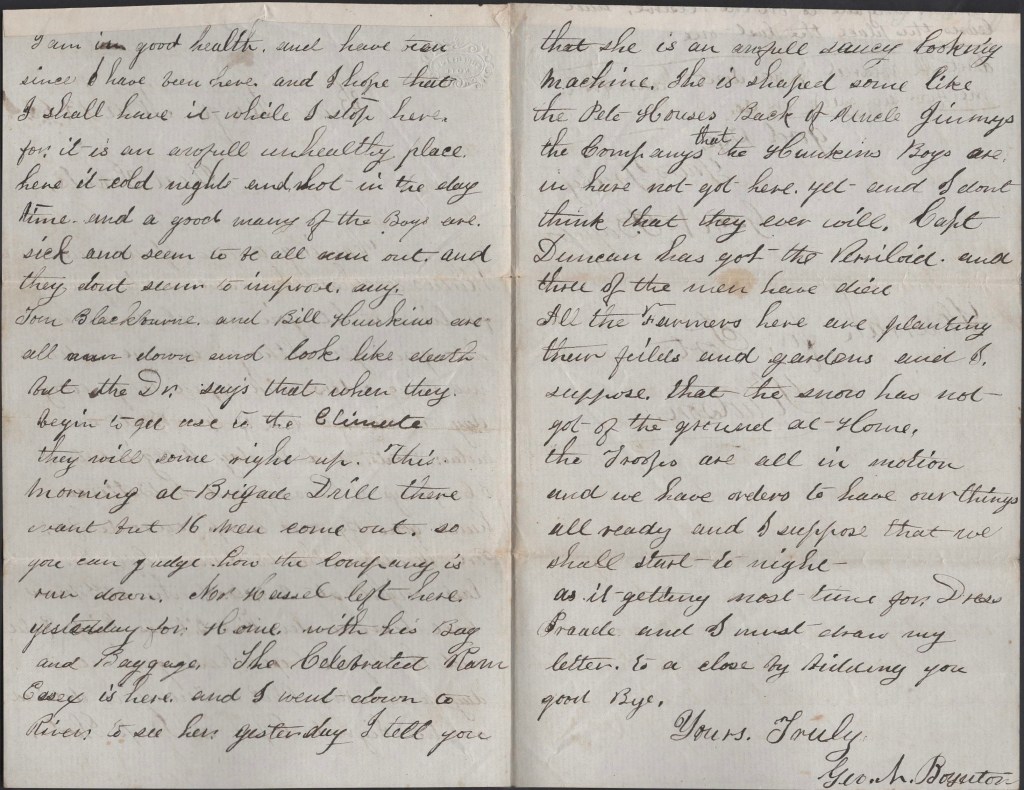

Letter 9

Baton Rouge

March 13, 1863

Dear Parents,

Having a few spare moments I thought that I would write you a few lines to let you know that we have not gone yet although we are under marching orders and expect to go every day. The river is full of gunboats and mortar boats and today four regiments & three companies of cavalry and four batteries have gone by our camp en route for Port Hudson. The 48th Mass. left here last night at 2 o’clock, the 41st Mass. have been under fire three times. Lieut. Runlet and the Signal Corps have gone out today to reconnoiter. Charles W. Tenney is detailed on the Signal Corps as sharp shooter.

I am in good health and have been since I have been here and I hope that I shall have it while I stop here for it is an awful unhealthy place here. It’s cold nights and hot in the day time and a good many of the Boys are sick and seem to be all run out and they don’t seem to improve any. Tom Blackburn and Bill Hunkins are all run down and lok like death but the Dr. says that when they begin to get use to the climate, they will come right up.

This morning at Brigade Drill there wasn’t but 16 men out so you can judge how the company is run down. Mr. [Robert] Hassall [chaplain] left here yesterday for home with his bag and baggage. The celebrated Ram Essex is here and I went down to the river to see her yesterday. I tell you, she is an awful saucy looking machine. She is shaped some like the peat houses back of Uncle Jimmy’s.

The company that the Hawkins Boys are in have not got here yet and I don’t think they ever will. Captain Duncan has got the varioloid and three of the men have died.

All the farmers here are planting their fields and gardens and I suppose that the snow has not yet got off the ground at home. The troops are all in motion and we have orders to have out things all ready and I suppose that we shall start tonight. As it is getting most time for Dress Parade and I must draw my letter to a close by bidding you goodbye. Yours truly, — George N. Boynton

Don’t be worried if you don’t hear from me for a week or so. Goodbye. Yours truly, — G. N. Boynton

Hurrah for Port Hudson!

Letter 10

Baton Rouge

March 26th 1863

Dear Father,

Having a few spare moments I though I would write you a few lines to let you know that I am well and as tough as a knot, although we have seen a rough time since I wrote you last. We left Baton Rouge on the 14th en route for Port Hudson. The first day we marched 15 miles and camped for the night and I had just got to sleep when orders came for us to report to Gen. Banks’ Headquarters which was about five miles so we formed in line and arched up there and as soon as we got there we had to go on guard that night, and the next morning we marched back to the regiment and stayed all day and that night I never see it rain so hard in my life. And [then] orders came for us to come into the pickets with an ambulance train which was about 4 miles and where we had to walk was in the gutter and mud and water up to your knees. And we marched to pickets and stopped for the night. I laid down and went to sleep and when I woke up, I was laying in two or three inches of mud and water. And just about that time, I thought I should like to be in Marm’s feather bed. It was awful hard work but I had a first rate time—especially when we halted.

The inhabitants were all secesh and the General told us that we could take anything that we could get our hands hold of and I tell you that we improved our chances by killing calves and sheep and I tell you that we lived high on fresh beef, pork, chickens, turkeys, eggs, milk, honey, and everything else that we could get our hands hold of. I went in one house that we came past and they had the table all ready for dinner and I sat down and eat what I wanted and when I got up to come off, the women that lived there gave me my canteen full of milk and a jar of honey.

There was one house that we passed that the man that owned it was a secesh and he stood in the door with his pistol in his hand and said that the first damned Yankee soldier that touched any of his things, he would shoot down and it wasn’t five minutes before we stole everything that he had and burned his house down on his head.

The next day we had orders to march back to Baton Rouge and take the boat there, go up the river 15 miles, and as there is not room on this paper to write our adventure, I will tell you about it in my next letter. So I will draw my letter to a close by bidding you goodbye. Yours truly, — G. N. Boynton

P. S. Don’t be worried if you see an account of a battle because our Brigade is a going to stop there.

Letter 11

Baton Rouge

March 30th, 1863

Dear Parents,

I have just received a letter from you dated the 9th and was very much pleased to hear from you in which you said that you wanted me to let you know how that I stood the guard duty and I am very happy to let you know that I stand it first rate and I am as tough and hearty as a boiled owl.

I wrote you last stating the trip that we had when we marched up to Port Hudson by land and ow I will give you an account of the trip up [by] river. We left Baton Rouge on the 14th [should be 18th] at about three o’clock in the afternoon on the steamboat Morning Light and we all thought that we had to see some fighting but as luck would have it the next morning we found ourselves in middle of a Rebel Colonel’s plantation stuck fast in the mud where the levy had been cut away and river flowed [over] the land. We stopped in this place until 12 o’clock the next day when we got off and continued our course up the river and landed on the Rebel General Winter’s plantation [four miles below and] in sight of Port Hudson on the opposite side and the Rebels found out what we was up to so they cut the levee above us and drowned us out.

While we stopped, we lived high [and] slept in the nigger huts. The sugar house on this place was six times as large as the Old South Meeting House and the store house full of sugar and molasses and we dived into. it and got all. we wanted. This plantation was the nicest place that I ever saw when we went to it, and when we left, it didn’t look quite so slick. We took all copper and the engine out of the sugar house and tore the old planter’s house all to pieces. The papers talk about the Rebels being in a starving condition when they are better off than we be for a regiment went out a foraging every day and they got just as many cattle, mules, horses, sheep, hogs, as they could drive in.

As it is about time for supper, I will draw my letter to a close. Yours, — G. N. Boynton

P. S. Our Division is a going to stop here and defend the place so you need not worry about my being shot if you hear of a battle.

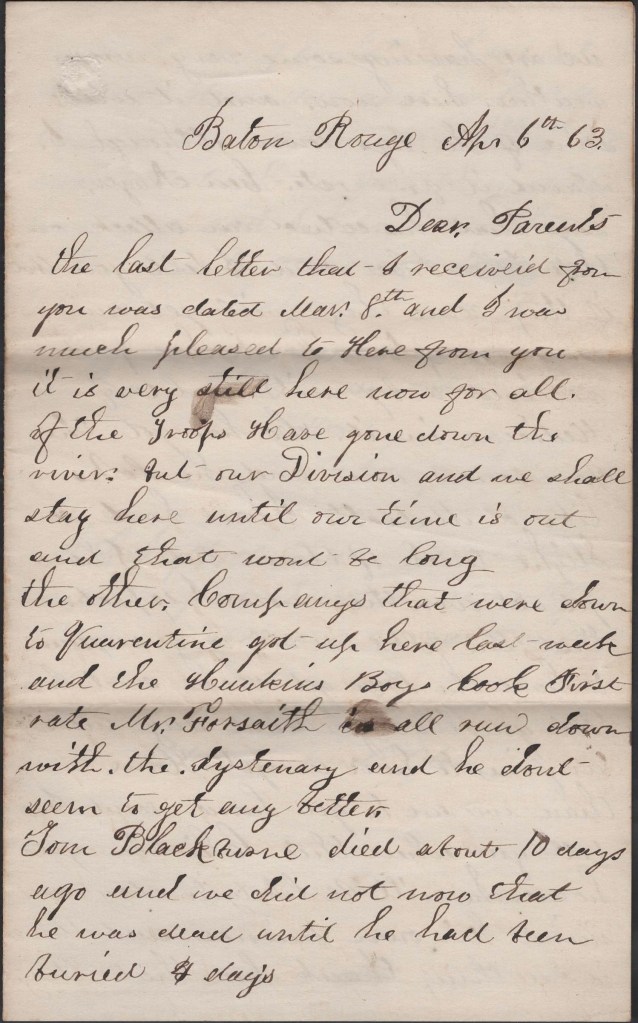

Letter 12

Baton Rouge

April 6th 1863

Dear Parents,

The last letter that I received from you was dated March 8th and I was much pleased to hear from you. It is very still here now for all of the troops have gone down the river but our Division and we shall stay here until our time is out and that won’t be long. The other companies that were down to Quarantine got up here last week and the Hawkins boys look first rate. Mr. Forsaith is all run down with the dysentery and he don’t seem to get any better. Tom Blackburn died about 10 days ago and we did not know that he was dead until he had been buried four days.

We are having some very warm weather here now and it wilts some of the boys down although I stand it first rate. Gen. Auger says that he expects an attack on this place and I tell you that if they come, they will get a warm reception. Frank has just received a box with a lot of medicine in it. He has got the jaundice now and he looks like a mulatto. I have had a slight touch of them but I have got all over them now.

I expect that the folks are all very anxious to have the Boys get home and I. tell you that they ain’t any more anxious to have us get home than we are to get home. And I tell you, when this chicken gets home, he will be likely to stay and mind his own business. And there is one thing, thank God that they can’t conscript him.

I expect that George Harnden and a lot of cowards around home are scared almost to death for fear they will have to go and I hope that they will have to come out here and take their whack at it.

As it is getting most dinner time, I must draw my letter to a close. Yours, — George N. Boynton

P. S. I expect that the women are in great demand about this time on account of the conscript act. Write soon and often.

Letter 13

Baton Rouge

April 10th 1863

Dear Parents,

I have just received a letter and two papers from you and I was much pleased to hear from you, it being a month since I heard from you before. We are having an easy time here now and the time slips away very fast. I am sorry to say that two of our company have died since I wrote you last. Mr. [William] Sides of Groveland and Milton Jewett [of Georgetown] died last night. He had a fever in the first place and it turned into a disease something like the Glanders.

I suppose that you are planting the garden about this time but out here the potatoes are in blossom and the corn is up about 20 inches. Lieut. Stowe of Co. G has broke his shoulder and Lieut. Bradstreet is all run down with the diarrhea. He looks like a skeleton. The Boys all hate Dr. [William] Cogswell the way that [he] delivers out medicine. He has a plate of Opium pills and he gives every man—no matter what the disease is—three of these pills. One morning when I went down there to get some medicine for a cold, he gave me pills and the next man came in and he asked him what ailed him and he said diarrhea and sick to his stomach and so he gave him 3 pills.

I am glad that I came out here for nine months for I never has so good a lesson in my life and when I get home, I can give you a good repensation of this war and the damned contractors for we have not had anything to eat but salt pork, bacon sides, and hard tack. But never mind. I shall be at home before a great while where I can get something decent to eat.

Tell Kenny to be a good boy for brother Georgey is coming home in 6 or 7 weeks. Amos Dole is sick and in the hospital and I should not think strange if we had to leave him out here under the sod for when these surgeons get hold of a fellow, he stands a poor sight to get out of it alive. And I tell you that they won’t get me into them hospitals if I can help myself.

As it is getting most dinner time, I will draw my letter to a close. Yours, — G. N. Boynton

P. S. I expect that Mrs. Marshall will have somebody on a string on account of this Conscription.

Letter 14

Baton Rouge

April 12, 1863

Dear Parents,

I received two letters from you last night and was glad to hear from you. Everything remains about the same as when I wrote you last. Our Brigade is a going to stay here. There [are] a lot of steamers down to New Orleans putting in bunks and provisions to carry the nine-month’s troops home. We shall probably start for home in 6 or 7 weeks as we have yet to be at home by the 15th of June and it will be the happiest day that I ever passed when I land in Old Georgetown and when it comes night crawl into Marm’s bed.

I suppose that the folks will have a great time when the Boys get home. Henry Butler’s the sutler plays it on the Boys like the Old Boy. I suppose that Father has as much business as he can tend to now—especially on the mail to Lawrence, and it will be a good job for me when I get home. Tell Kenny to be a good boy and keep his nose clean.

Mr. Forsaith is improving and he is on duty. His company is doing Provost Duty in the City and he has charge of a slaughter house. Lyman Floyd is a going to have his discharge and probably will start for home inside of a week. Lieut. Bradstreet has gone to the hospital and we are all trying to have [him] resign and go home. But he says that [he] won’t go. until the company does. The company has been under the Sol ever since we have been here.

Capt. Barnes has all flushed out and he don’t amount to Hannah Cook and the Boys all hate him worst than they do the Devil.

We don’t have to drill only two hours and when we go on guard, we have sentry boxes to stand in and they keep the sun off of you first rate.

I had a letter from Uncle Kendall and he said that Jenny had left you in an awful rush and I want you to write me the reason that she had to leave. As it is getting most time for drill, I must draw my letter to a close. I am well and in good health. Yours truly, — George N. Boynton

Letter 15

Baton Rouge

April 22, 1863

Dear Parents,

Yours of the 2nd is received in which you sent them bills on George Curtis and John Perry. We shall probably get paid off in course of a fortnight. Dr. French, our Asst. Surgeon, died this morning and all of our officers are sick and the company is in charge of the 3rd Sergeant but I am fat and saucy and I never was so fleshy in my life. Our regiment has got straw hats and mosquito bars. The report is here that the Government is a going to keep us until August 11th but our officers do not believe it. But if they do try it, there will be a general howl in the regiment.

I wrote to Esther and Uncle Eben a month ago. It is awful weather here now, but we don’t have to drill only an hour a day. But we have poor grub. It consists of ham and bacon sides, or hogs smoked. Rather than to eat the nasty stuff, I have bought the most of my grub. I think that we shall start for home by the last of next month and you can make up your mind to see me by the middle of June. Bill Hankins has just got out of the hospital and he looks rather slim but is gaining fast. Capt. Barnes and Lieut. Bradstreet are in the hospital. When we get into Boston and get mustered out of the service, I guess that he won’t have many followers.

I wrote a letter to Uncle Kendall about two weeks ago and I suppose that he has got it by this time.

I suppose that the Hot Abolitionists are in an awful panic for fear that they will be drafted and I hope that they will have to come out here and take a hack at it. Frank has to toe the mark. They only had him on knapsack drill of 2 [ ] for skipping drill and [ ] and his folks sent him some medicines and he has sold it all. I don’t want [you] to say anything to his folks about it.

As it is getting most dinner time and we are a going to have baked beans for dinner, I must draw my letter to a close. Yours, — G. N. Boynton

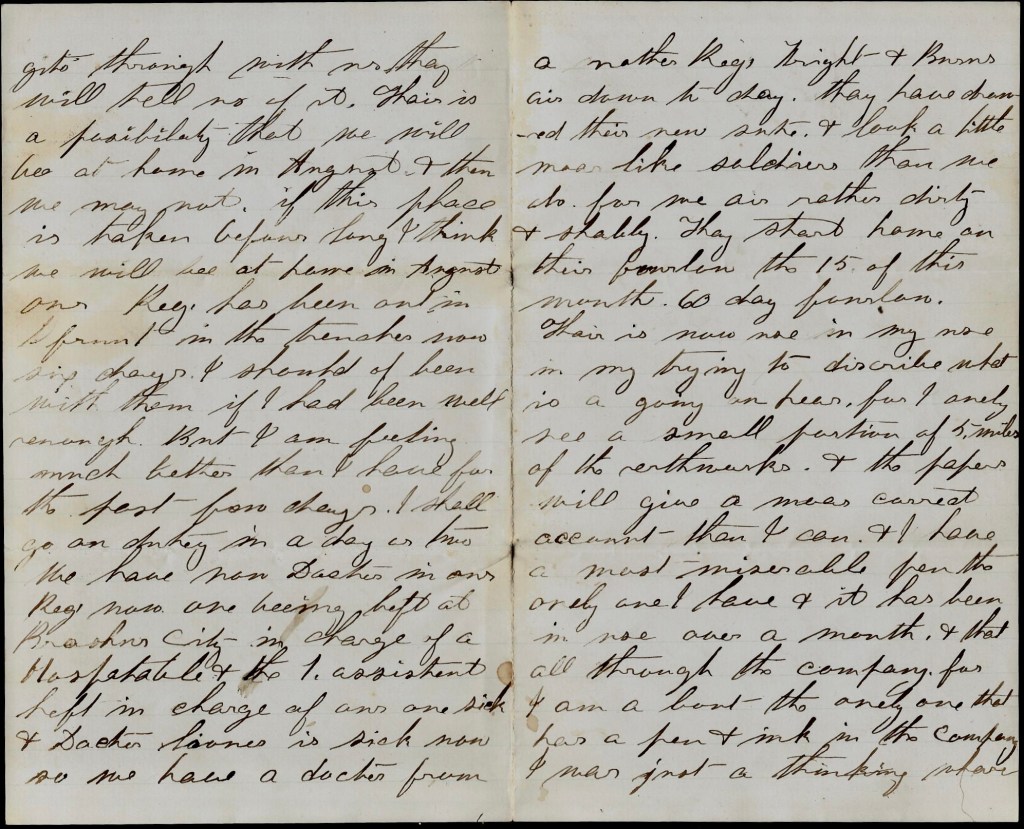

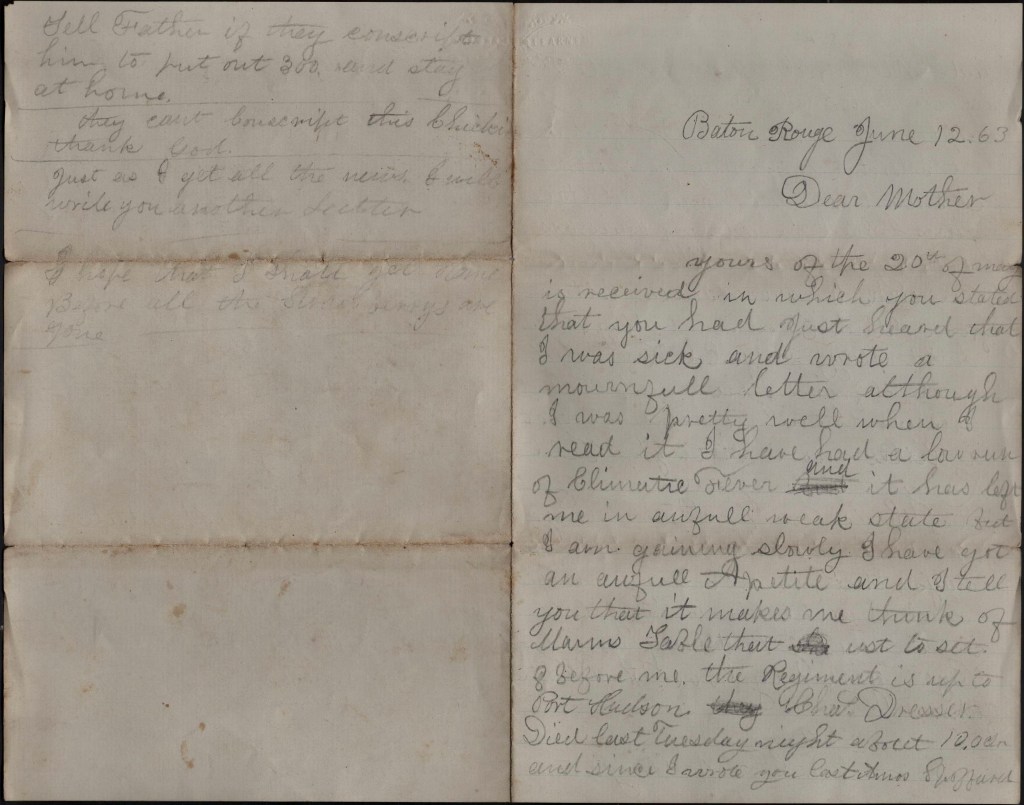

Letter 16

Baton Rouge

June 12, 1863

Dear Mother,

Yours of the 20th of May is received in which you stated that you had just heard that I was sick and wrote a mournful letter although I was pretty well when I read it. I have had a low run of climatic fever and it has left me in awful weak state but I am gaining slowly. I have got an awful appetite and I tell you that it makes me think of Marm’s table that used to sit before me.

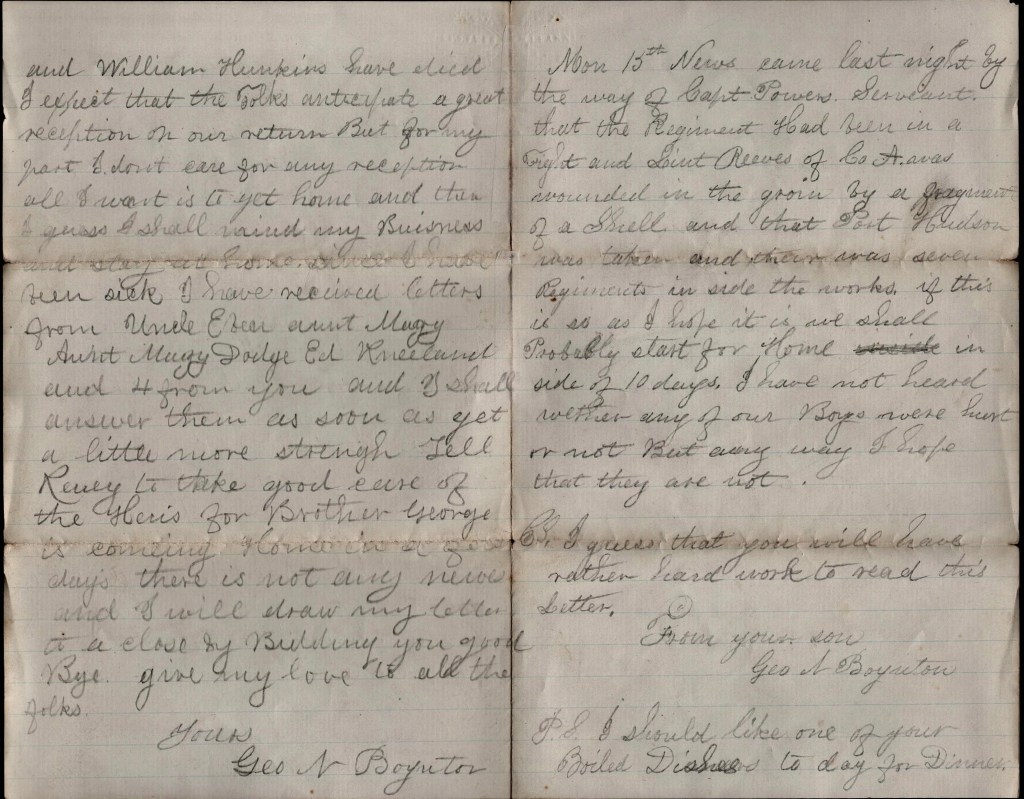

The regiment is up to Port Hudson. Charles Dresser died last Tuesday night about 10 o’clock and since I wrote you last, Amos Spofford and William Hunkins have died. I expect that the folks anticipate a great reception. All I want is to get home and then I guess I shall mind my business and stay at home. Since I have been sick, I have received letters from Uncle Eben, Aunt Maggy, Aunt Maggy Dodge, Ed Kneeland, and four from you and I shall answer them as soon as I get a little more strength. Tell Kenney to take good care of the hens for brother George is coming home in a few days.

There is not any news and I will draw my letter to a close by bidding you goodbye. Give my love to all the folks. Yours, — George N. Boynton

Monday, 15th. News came last night by the way of Capt. Powers’ servant that the regiment had been in a fight and Lieut. Reeves of Co. A was wounded in the groin by a fragment of a shell and that Port Hudson was taken and there was seven regiments inside the works. If this is so, as I hope it is, we shall probably start for home inside of ten days. I have not heard whether any of our Boys were hurt or not but anyway, I hope that they are not.

P. S. I guess that you will have rather hard work to read this letter. From your son, — George N. Boynton

P. S. I should like one of your boiled dishes today for dinner. Tell Father if they conscript him to put out $300 and stay at home. They can’t conscript this chicken, thank God. I hope that I should get home before all the strawberries are gone.

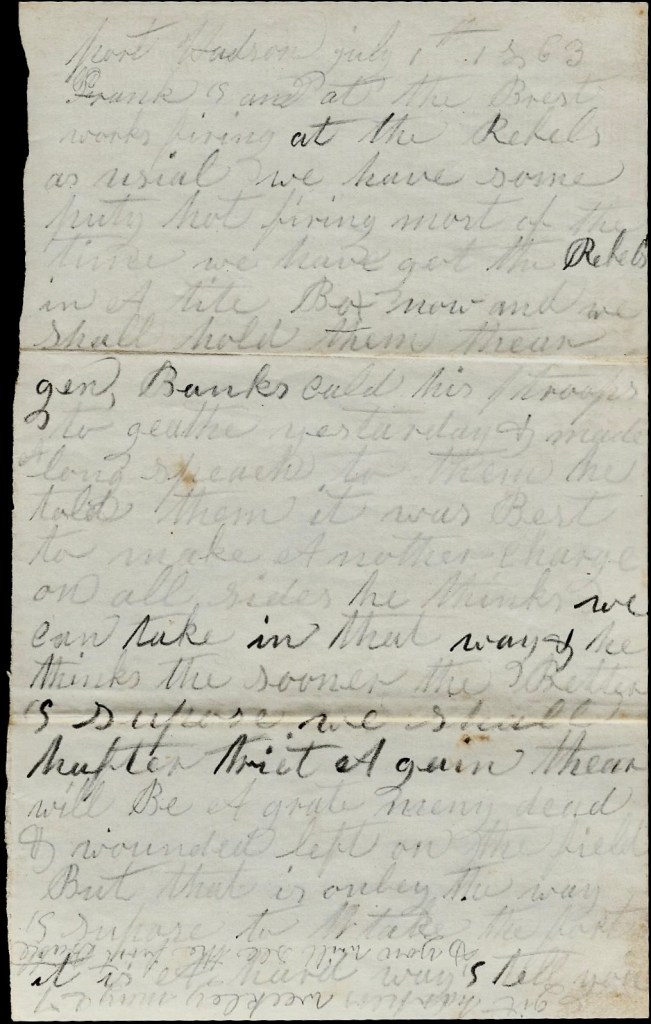

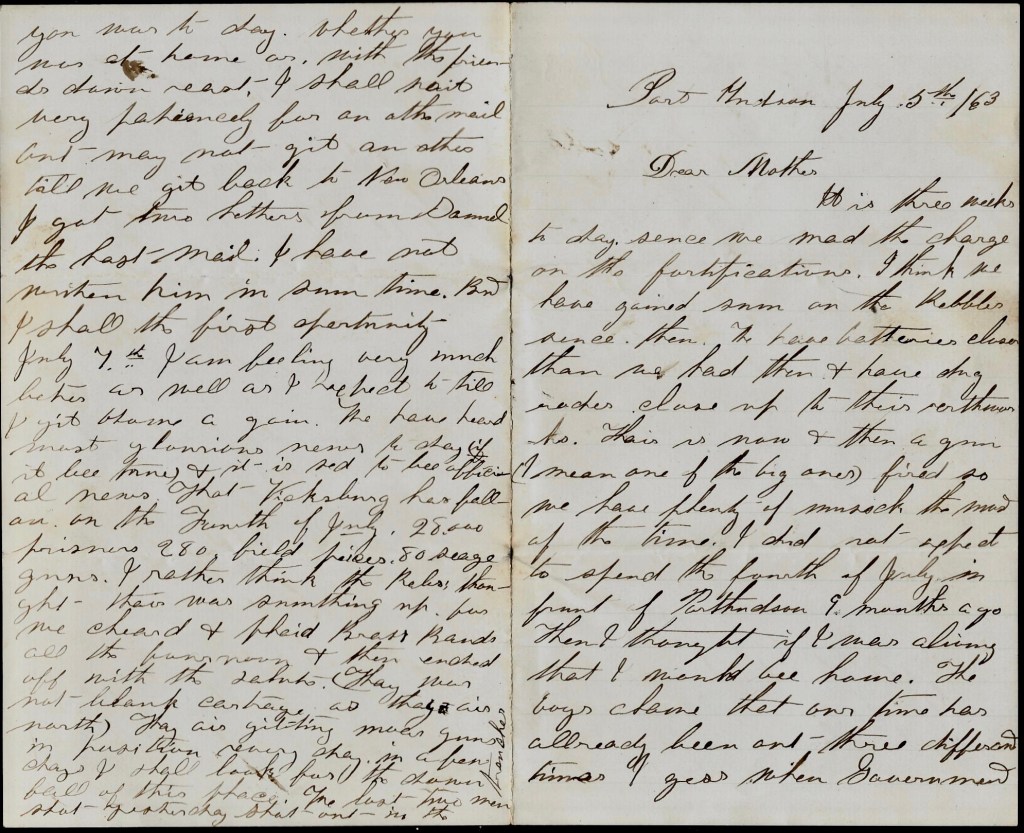

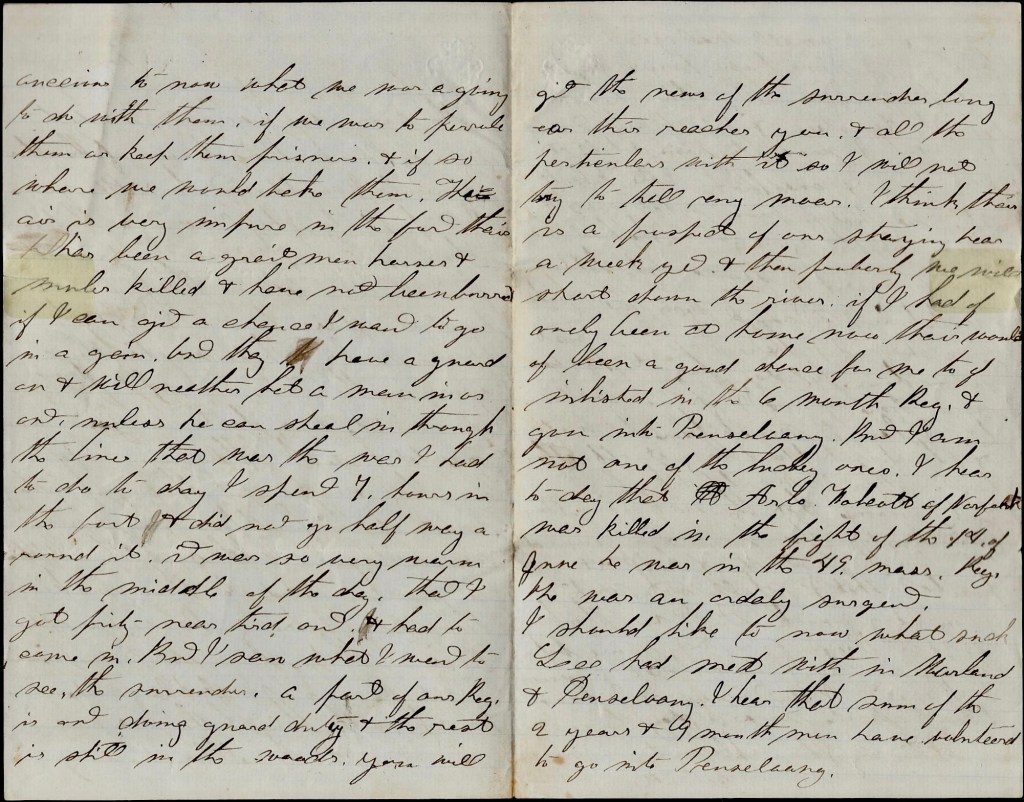

Letter 17

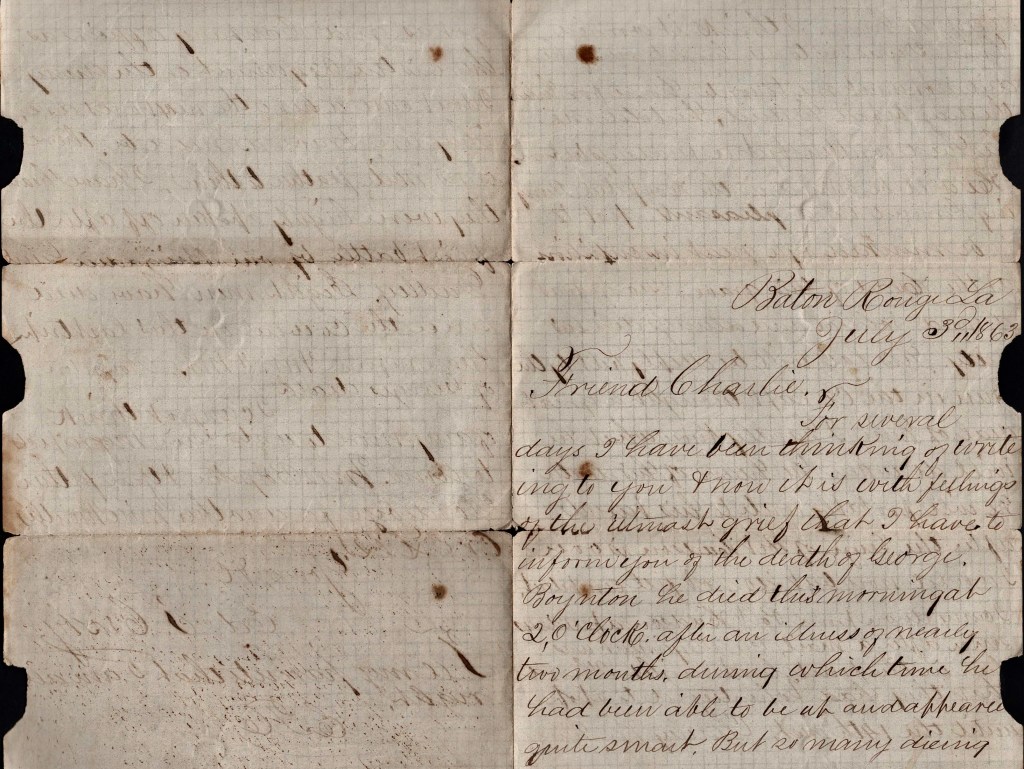

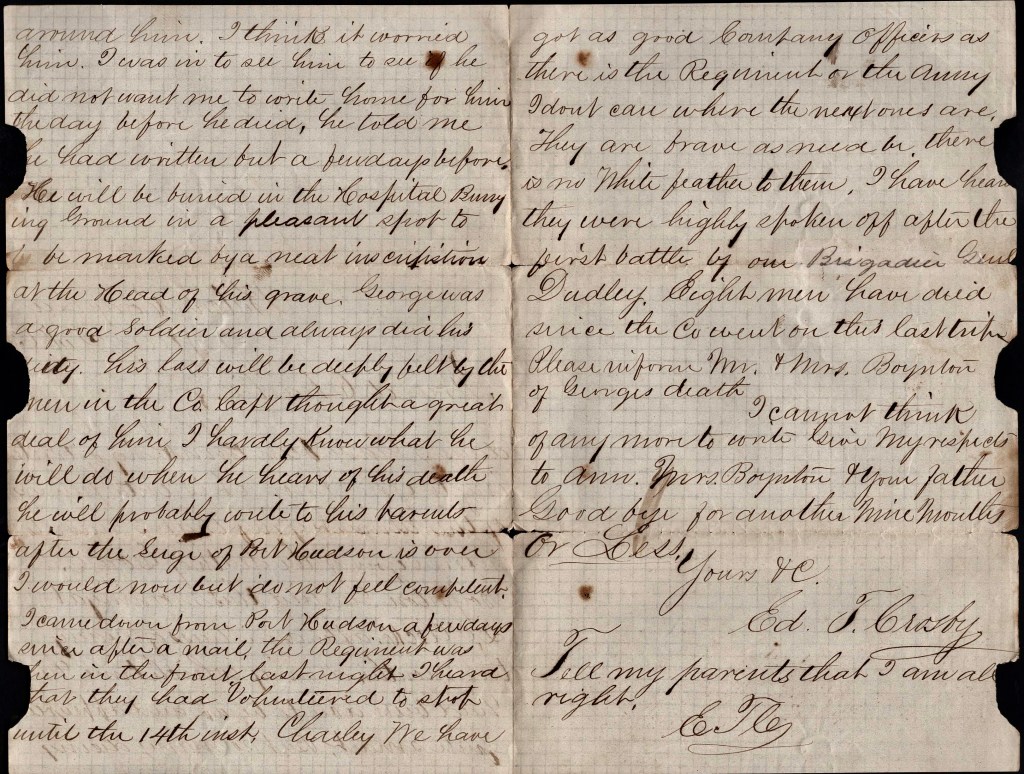

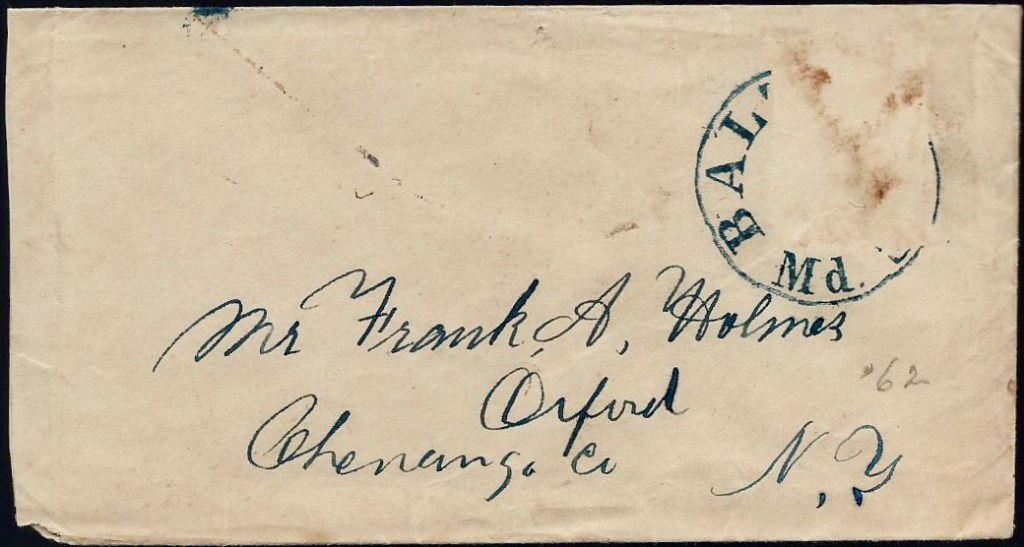

Note: The following letter was written by Edward T. Crosby of Co. K, 50th Massachusetts Infantry. He died of disease a month later, 4 August 1863, onboard a steamer on the Mississippi River.

Baton Rouge, La.

July 3, 1863

Friend Charlie,

For several days I have been thinking of writing to you & now it is with feelings of the utmost grief that I have to inform you of the death of George Boynton. He died this morning at 2 o’clock after an illness of nearly two months during which time he had been able to be up and appeared quite smart. But so many dying around him, I think it worried him. I was in to see him to see if he did not want me to write home for him the day before he died. He told me he had written but a few days before.

He will be buried in the Hospital Burying Ground in a pleasant spot to be marked by a neat inscription at the head of his grave. George was a good soldier and always did his duty. His loss will be deeply felt by the men in the company. Captain [Barnes] thought a great deal of him. I hardly know what he will do when he hears of his death. He will probably write to his parents after the siege of Port Hudson is over. I would now but do not feel competent.

I came down from Port Hudson a few days since after a mail. The regiment was then in the front. Last night I heard that they had volunteered to stop until the 14th inst.

Charley, we have got as good company officers as there is [in] the regiment or the Army. I don’t care where the next ones are. They are brave as need be. There is no white feather to them. I have heard they were highly spoken of after the first battle by our Brigadier General Dudley. Eight men have died since the convention on this last trip. Please inform Mr. & Mrs. Boynton of George’s death.

I cannot think of any more to write. Give my respects to Ann, Mrs. Boynton, & your father. Goodbye for another none months or less. Yours, &c. — Ed T. Crosby

Tell my parents that I am all right.