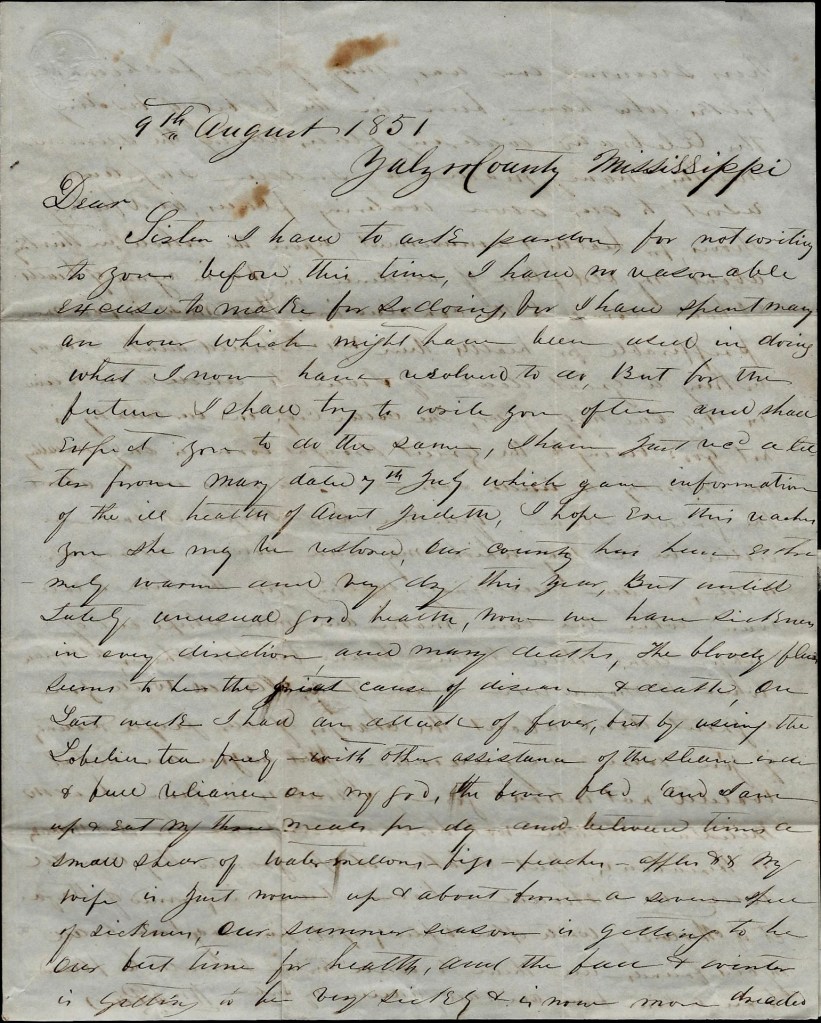

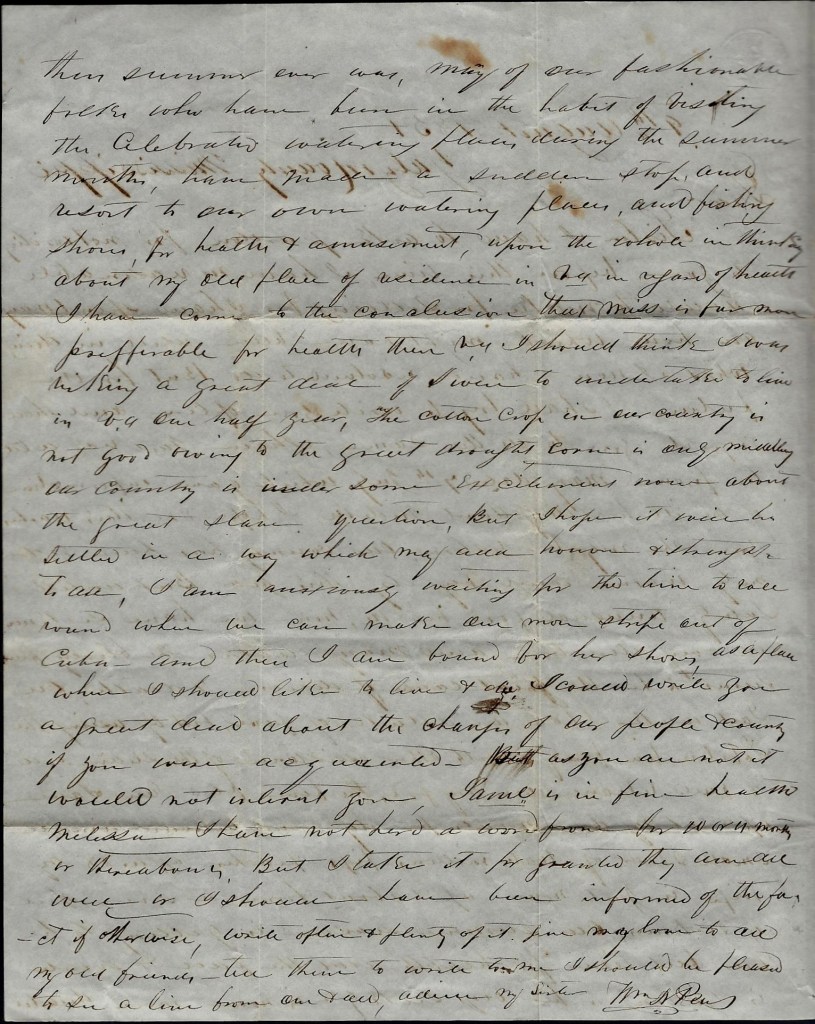

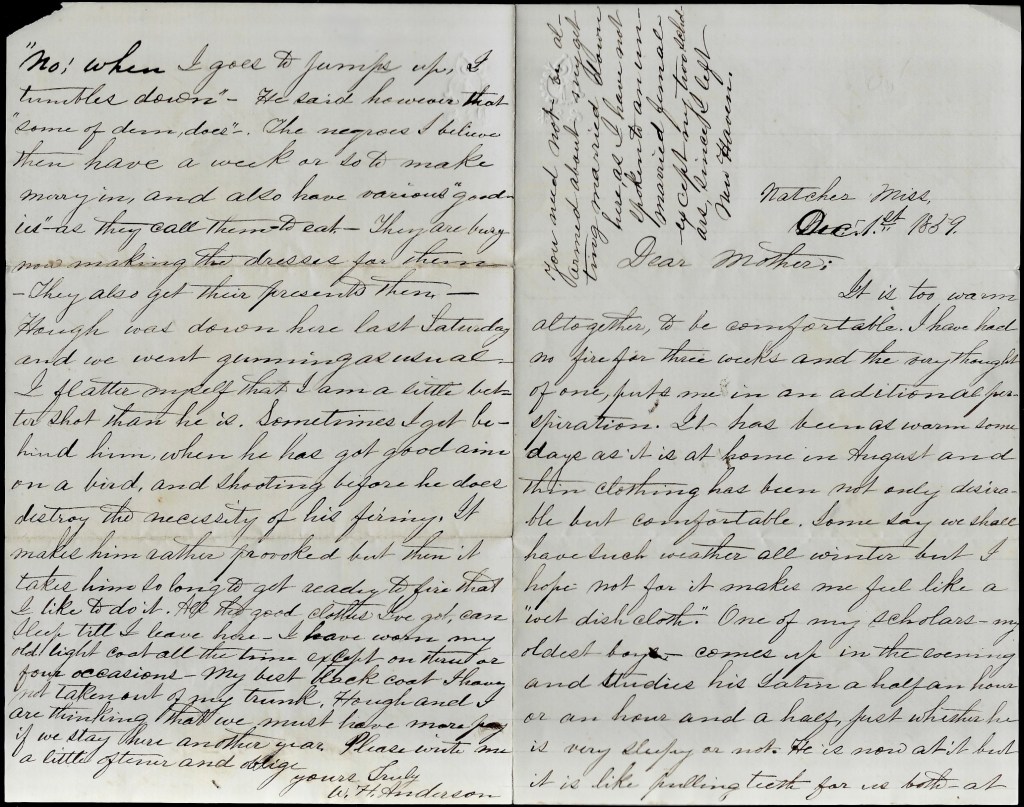

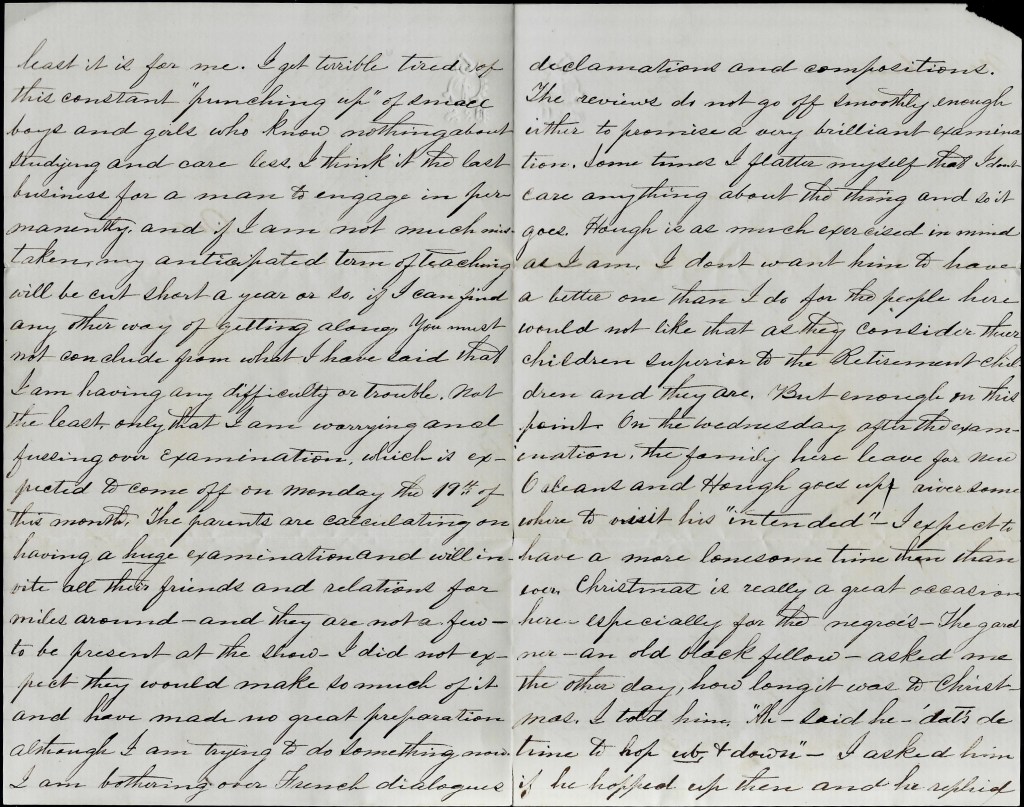

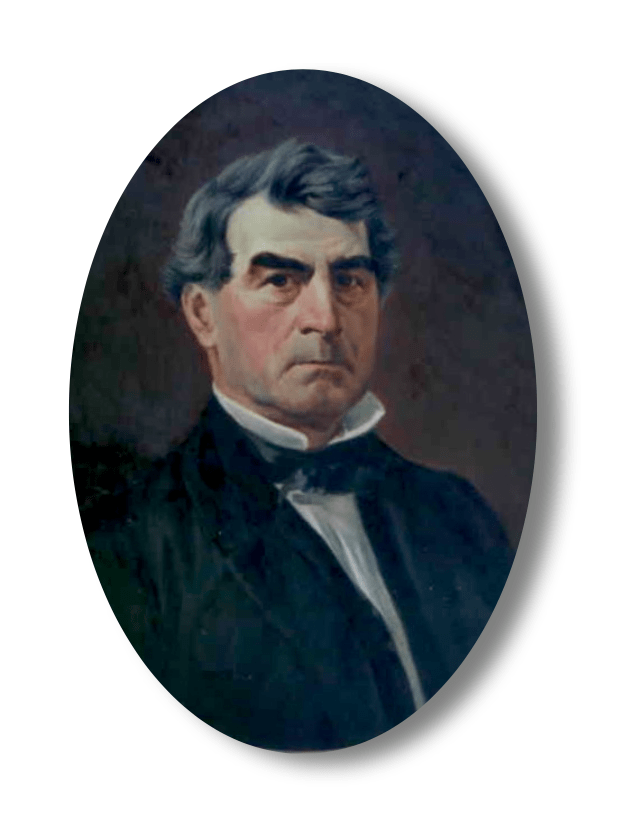

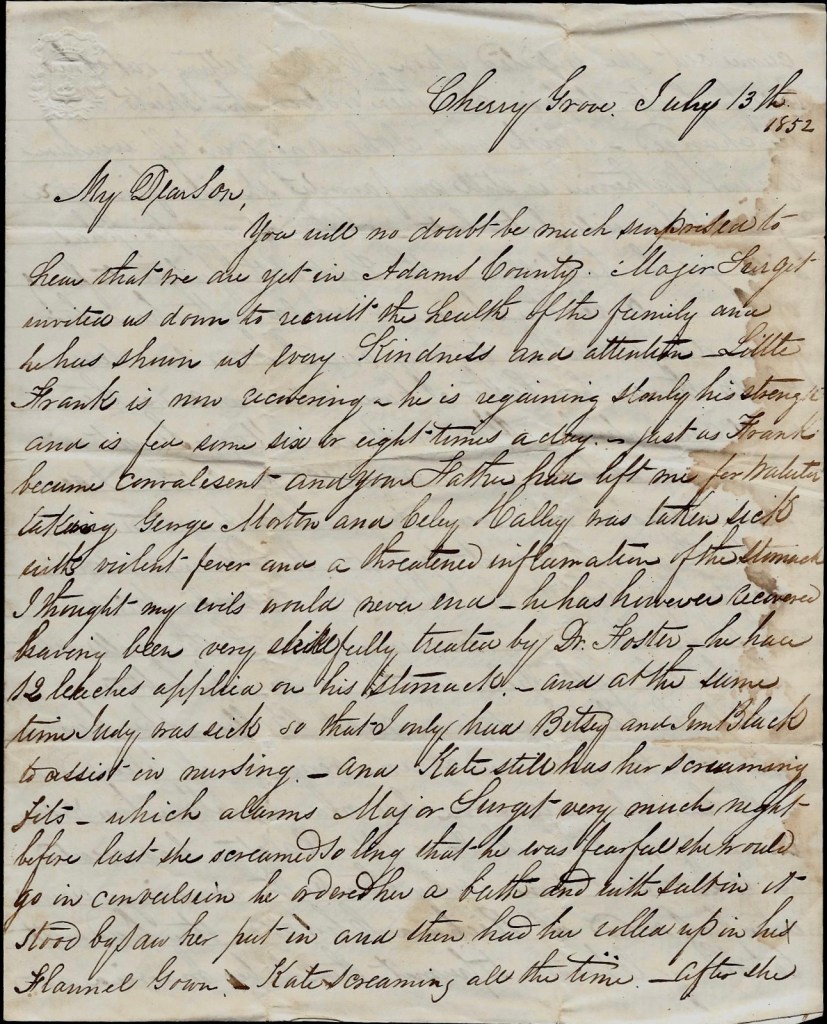

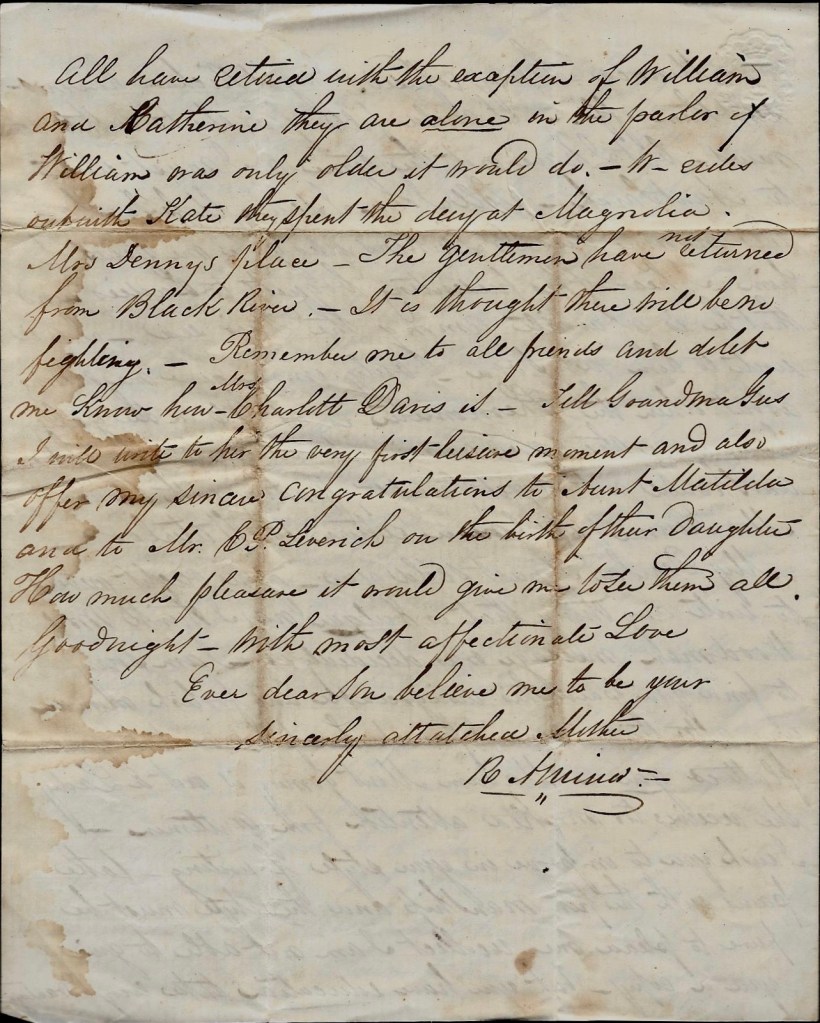

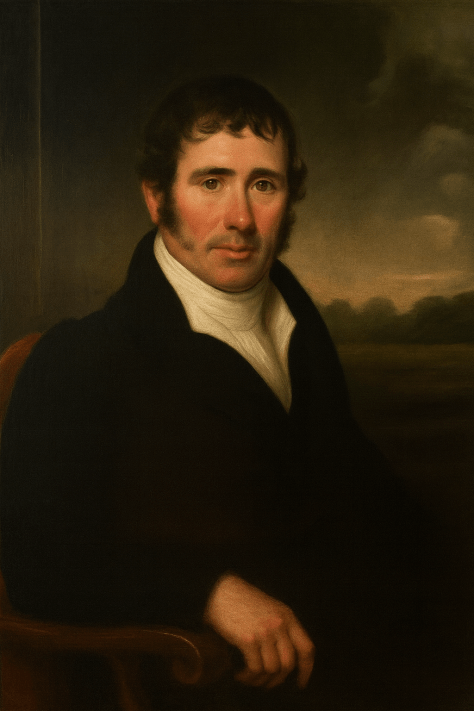

This letter was written by Thomas Henry McNeill (1821-1866), the son of Malcom McNeill (1796-1875) and Martha Rivers. Malcom McNeill began accumulating property in Kentucky where he relocated in 1817, and later bought thousands of acres in Mississippi and within the city of Natchez, which greatly increased in value. An 1884 history of Christian and Trigg counties as “perhaps the richest man in the county, with a large estate and many negroes both there and in Mississippi.”

Thomas Henry McNeill first went to Mississippi to tend his father’s plantations there which were sited along the Mississippi River. He began purchasing his own lands in 1853, initially in the extreme southwestern corner of Coahoma Co. near his father’s plantation in that area. He accumulated 1,945 acres on the Mississippi River there, including a gift from his father of 698 acres. In 1857 he purchased 1,100 acres about ten miles north but still on the River, and sold the southern properties. He called the new plantation “Dogwood” and the Mississippi river now flows over half of that property.

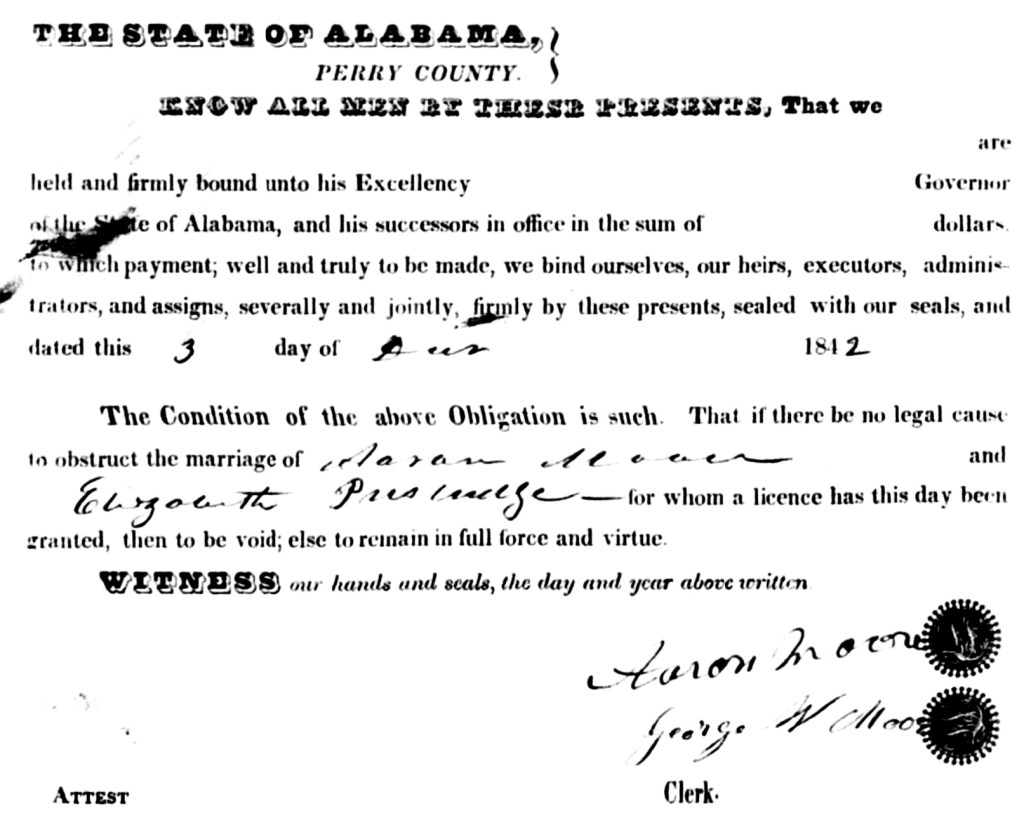

Thomas married first Rebecca Ann Tuck, daughter of Davis Green Tuck and Elizabeth M. Toot, on 26 October 1842 in Christian County, Kentucky. He married second Ann Eliza Arthur, daughter of William Arthur and Susannah Hill Peters on 11 June 1861 in Marshall County, Mississippi. He died at his plantation in Coahoma County, Mississippi at age 45.

T R A N S C R I P T I O N

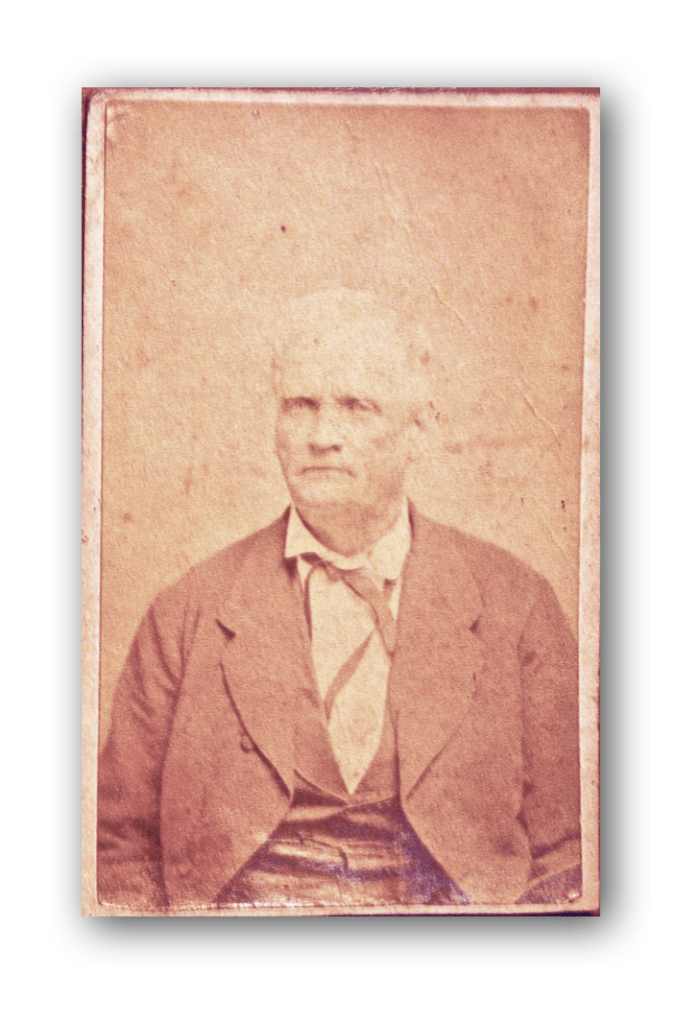

Buena Vista, Coahoma, Mississippi

Monday, June 12, 1848

My dear Father,

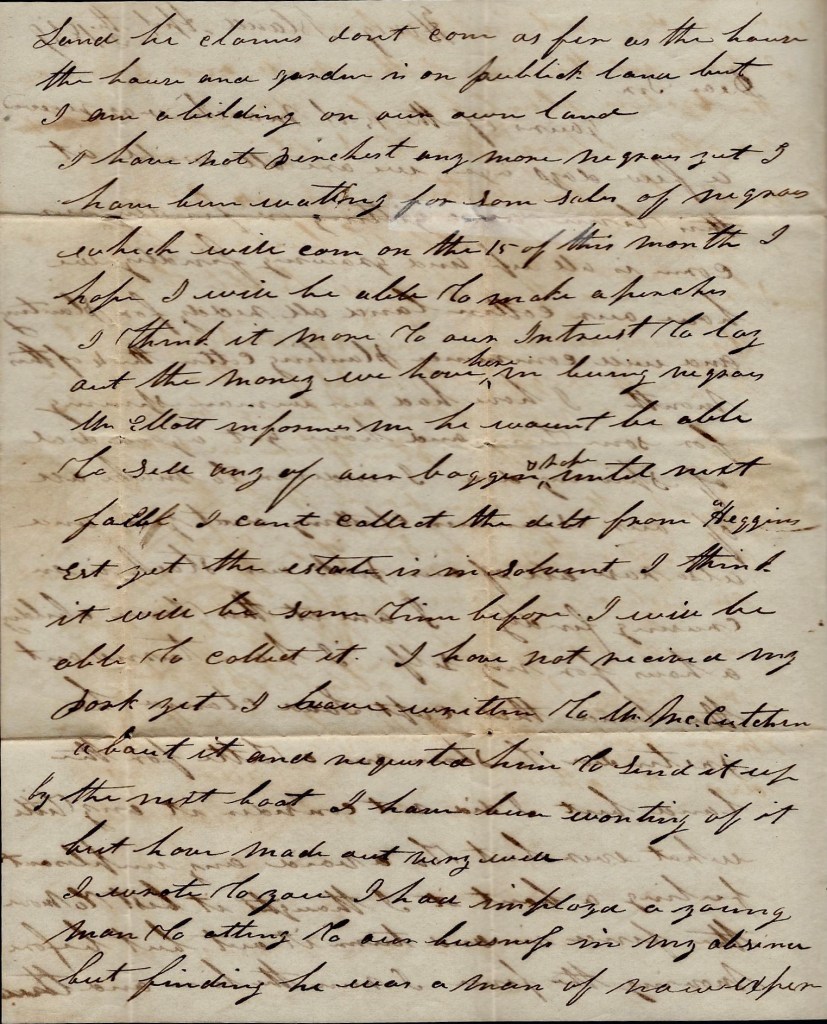

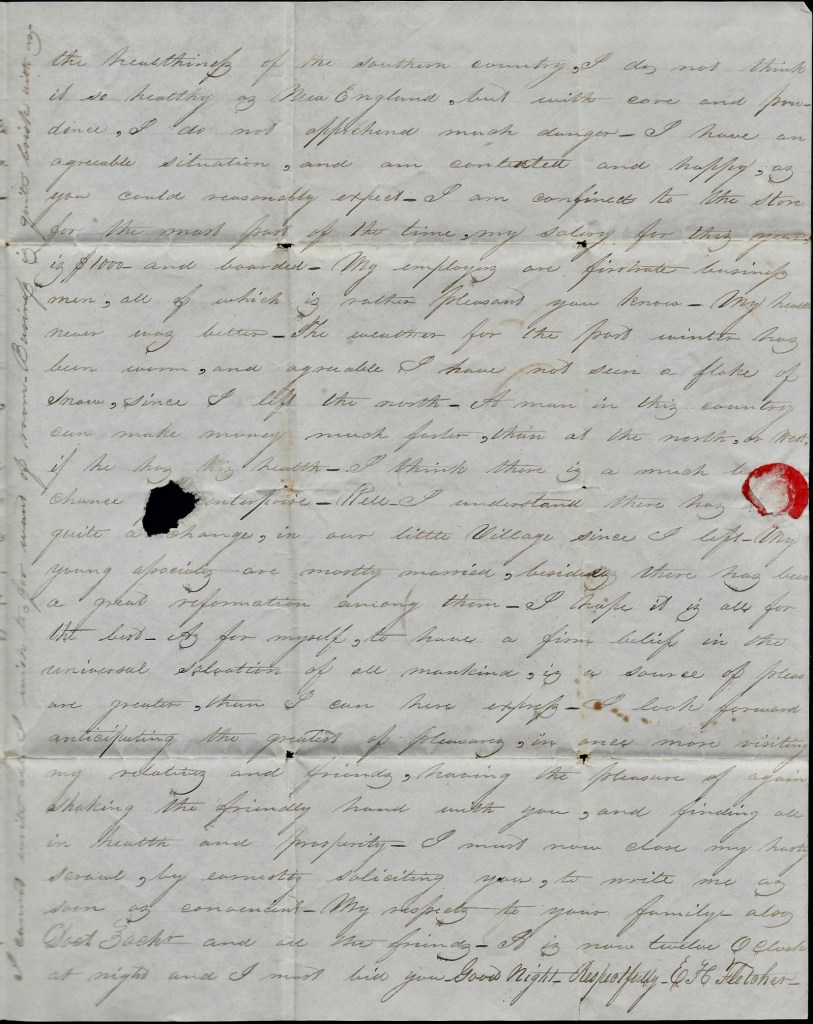

Your ploughs were engaged during the whole day of Monday in laying by your corn on the Lake cut. They commenced Tuesday the other piece which was finished about noon. They then broke up those low, wet places between your cotton and my cotton, plowed over all the small corn. Those low places were planted by Emily & Amrett in corn. Your hoe gang only finished your corn on Monday. On Tuesday they finished that portion of new ground which you left undone. Hoe men were started to getting [ ] and are getting 15 hundred per day. The hoe’s after finishing the little that you left, went into the latest new ground and chopped it over.

On Wednesday fifteen plows (Monday & Tuesday Harich [?] was sick) and the hoe’s started in the cotton opposite your lake corn—the piece near the Irishmen’s levee—which the plows finished about 3 o’clock. They then commenced the piece over the Bayou which was finished on Thursday at nine. They then plowed that young cotton over the levee by 12 o’clock. After dinner they commenced the Walnut Ridge which was finished Friday morning early. They then went into the eighty acre field which they finished about 4 o’clock. They then plowed the piece of cotton on Lake Charles, back of the gin which was finished about 10 o’clock on Saturday. They then plowed those two pieces near the negro cabins, finishing all your old land cotton one hour by sun on Saturday.

I left your hoe gang in the office near the Irishman’s Levee on Wednesday which they finished that just at night. Next morning (Thursday) they went over the Bayou and to the Second year’s cotton which was finished about 3 o’clock same day. The hoe hands that evening cleaned out th bayou very well as your other cotton had all been gone over by the hoe gang just before the plows. Your hoe’s went in the new ground on Friday late (as the women had to wash) the piece nearest my second years, which they chopped over well that day, finishing a little before night. They then commenced the nearest piece to them (that is the second ridge) which they about half finished on Saturday night.

Saturday very late in the evening we had an awful tornado which has injured our crops very much, particularly your large corn. The cotton, I hope, will all straighten up soon. The wind blew down very many trees in the Plantation. On Saturday night, we had a very heavy rain. Another on Sunday during the day and it has been raining very hard all the morning up to 9 o’clock. The quantity of rain fallen has been immense, rendering it impossible to plow in old grounds for a day or so. All your plows are in the new ground nearest to my gin. On examining your new ground the day after you started (which was the 13th) I found three [cotton] blossoms. We have now a great many but they are not fully blown, which is attributed to the last few days having been very cloudy. One or two days sun will show a great many.

This letter will be dropped at Line Port by the Steamer Talleyrand. I will leave it open until she arrives. Your negroes (except Harick) are all well, but showing considerable disposition to lay up, or in other words, to possum.

Tuesday morning, June 20, the boat has not yet arrived and I am on the eve of starting to the lands. After another light shower yesterday the weather has cleared off beautifully and seems likely to remain so for a few days. I close now for fear the boat should come in my absence. My respects to Mother. Your son, — Thos. Henry McNeill

Tuesday 12 o’clock. Your plows finished the field next to my second year’s land. After dinner they will go into the piece adjoining the first. The hoe’s chopped over the second piece. The old ground is yet too wet to go into. Your corn is shooting very finely but the crows are injuring it already. All the hands are out today. Three laid up yesterday—Libby, Priss and Parthenia—who I think had chills. Directed Hoages to give quinine today and tomorrow. I saw blooms in my long [ ] today for the first time. The weather seems more settled and we shall have a great many in three or four days. Mother’s poultry are doing very well. No deaths in that line except the old gobbler which died the day after you left. Your son, — Thos. Henry

As we had to put Clark to getting boards, I made a plower of Gabriel who does very well in old land. He has never attempred to plow in the new ground so we are only running fourteen plows. I cannot say what time I shall leave. Perhaps not at all. My health is not as good as when you left yet I am up and attending closely to our business. I am making an effort to get two hundred acres well cleared this summer.

I had all my hands in my new ground clearing all last week and will be in there the whole of next week. Hoages had a good many trees belted in your plantation but the rains have filled up the sloughs so full that he cannot as much more until the water goes down, We are all getting on very well and our crops in much better order than when you left us. Cousin Hector is not yet out of the grass. He is making a desperate struggle…